Happy Birthday, Tris, and In Case you missed…

In case you missed this week’s post: By the Numbers and 1916

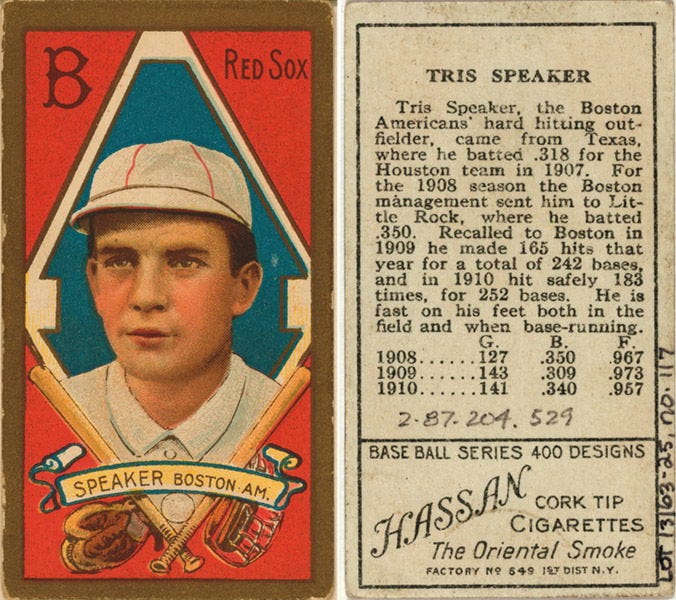

Happy Birthday, Tris! April 4, 1888

The 1908 Little Rock Travelers struggled to make ends meet despite the good fortune of having one of the greatest players in baseball history on their roster.

A complicated deal resulted in a handshake promise that Tris Speaker would spend the entire 1908 season in Little Rock. Even the good fortune of having a Future Hall of Famer that Joe Posnanski ranked as the 18th best player in baseball history would save a franchise on the brink.

Friday, September 4, 1908, was a rainy late-summer day in Little Rock. So rainy in fact, that the Travelers’ afternoon game with the Atlanta Crackers was called in the fifth inning tied at two. Perhaps an early ending was a good thing for Little Rock center fielder Tris Speaker. He had a train to catch. That evening, Speaker would be leaving for Boston for his third trial at the major league level. He would not play in another minor league game for twenty years. During that Hall of Fame career, he would secure his place as one of the greatest major league outfielders of all time.

Arriving that evening from Hot Springs was Speaker’s replacement, a promising young outfielder named Rupert Blakely. The 22-year-old Ouachita College student from Coal Hill, Arkansas, had hit .370 in the Class D Arkansas State League. It was a big jump from the Hot Springs Vapors to Class A Little Rock, but Blakely looked like a big-league prospect eventually bound for the same destination as his Travelers’ predecessor. Although Little Rock’s departing and arriving center fielders passed in the night, they likely never met. Their lives were destined to be lived out in two very different worlds.

The 1908 Little Rock Travelers had Tris Speaker in center field surrounded by a cohort of minimal talent that would finish the season seventh out of eight teams. Although team success was minimal, sportswriters seemed to know immediately that their center fielder was special. One hyperbole-laden account described Speaker’s grace in center field as moving as smoothly as “A globule of mercury in a prism puzzle.”

The Travelers opened the season with two losses to Memphis, and by the first week of May, the team had settled into last place. Speaker did not have an extra base hit in the first dozen games, but unlike the team’s lack of success, he would soon catch fire at the plate.

Perhaps no game in the early season was more indicative of the Travs’ inauspicious outlook and Speaker’s impending stardom than a 4 - 0 loss in Mobile on May 2. Tris Speaker had two hits in the loss, to raise his average to near .300, and he made an unusual defensive play that would become a part of his distinguished baseball resume.

Speaker had decided, based on his personal uncalculated analytics, that teams were damaged more by singles that fell in front of the center fielder than doubles and triples that sailed over the outfielder’s head. Based on his theory, he played center field like a rover in 10-player softball, about 90 feet behind second base, daring hitters to try to hit the ball over his head.

In the game at Mobile, with a runner on second base, Sea Gulls’ shortstop Paul Sentell hit a fly to short center. Woody Thornton, the Mobile baserunner on second base, assumed the ball would drop and headed for third. Speaker raced in on the sinking blooper, made a running catch, and without slowing down, sprinted toward the infield to double Thornton off second base. Speaker would continue to make unassisted double plays throughout his career and establish the rare defensive gem as a signature piece in the legend of Tris Speaker.

By mid-May, the Travelers had climbed to seventh place, their eventual final destination in the standings, and were earning the harsh words they read in the local press. Their center fielder, on the other hand, had reached the top of the league hitting stats and was getting considerable positive attention.

In a home loss to first-place Memphis on May 9, the Arkansas Gazette colorfully described the situation in derisive Texas’ verbiage, “Like a fire on dry prairie grass, they (Memphis) swept over West End Park.” “Speaker was the ‘Lone Star.” In the Memphis dugout, future major league pitcher Rudy Schwenck commented, “Boys, there’s a fellow that’s got no business in the minor leagues.”

After one rotation through the Southern Association, Little Rock sportswriters were willing to declare that the Travelers’ center fielder “outclassed anything in the South.”

Opponents agreed. There was indeed a fellow in Little Rock far above the Southern Association norm. When Memphis came to town in mid-June, team executive William McCullough accompanied the team and brought his camera, not to get photos of the Memphis Egyptians, but to photograph Tris Speaker.

Bristol Lord, of the New Orleans Pelicans, who had played 100-plus major league games, pushed Speaker in batting average the first half of the summer, but the outfielder in Little Rock known as “Finn’s Find” was the unquestionably most respected player in the Southern Association. Although crediting Manager Mike Finn for finding Tris Speaker is a stretch, keeping him for a season, and letting him develop his creative style is a credit to Finn’s astute judgement.

Finn let Speaker be Speaker. He allowed Tris to play so shallow in center field that he made unassisted double plays and intentionally dropped fly balls to force runners who assumed he would catch the easy blooper. He ran the bases with abandon, didn’t like to walk, and seldom struck out. Finn, not a baseball man by training, was the perfect manager for Speaker. The shrewd little skipper’s confidence allowed Speaker to refine the unique style of play that would be his trademark throughout his career.

By August, Speaker’s batting average had slipped somewhat to .330, still comfortably the best mark in the league. In addition to leading the league in every significant hitting category, Speaker gave center field a new personality. To baseball men, center field had a defined purpose. To Tris Speaker, playing a position without being responsible for a base allowed him to create an offensive strategy for a defensive position. He willingly gave up a triple or two to lead the league in assists, putouts, and, of course, double plays.

On August 27, with the deadline for claiming minor leaguers rapidly approaching, Little Rock newspapers reported the inevitable. Southern Association President Williams Kavanaugh of Little Rock had received a check from Boston for $500 to “reclaim” Tris Speaker. Although the Travelers were offered considerably more for the 20-year-old phenom, Mike Finn was a notorious man of his word. Regardless of the compensation, Speaker was headed to the big leagues, and Little Rock had enjoyed his services for most of the 1908 season. The deal is complicated and often debated, but the result was incontrovertibly simple. Tris Speaker had perfected his superstar skills in Little Rock, Arkansas.

The last month of Speaker’s term in the Southern Association was one of his best stretches of the season. He raised his batting average to .350, 36 points better than Bris Lord’s .314. He also led the league’s hitters in hits, runs, and extra-base hits. Speaker’s redefined center field strategy resulted in league-leading totals for outfield assists, putouts, and double plays.

That rainy September evening when he caught the bus for the major leagues, Tris Speaker was bound for Boston and eventually the Baseball Hall of Fame.

“Inevitably, all outfield stars will be compared to Speaker and inevitably all will suffer.” Joe Williams, Cleveland Press

____________

A Subscription sends the weekly post to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link