Backroads and Ballplayers #99

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Nothing New in Baseball, By the Numbers, and 1916

Opening Day comes and goes with no big news.

Aaron Judge is on track to hit 214 home runs.

At the pace the Yanks are hitting homers, we can expect the team to hit somewhere around 800 homers, breaking the current team record by about 500.

The Dodgers have purchased a bunch of guys who may go undefeated.

The St. Louis Cardinals’ amazing front office led everyone to think the roster was not improved. The sly way they made folks believe they wanted to trade Nolan Arenado was nothing short of genius. That unconventional style of general managing has the Redbirds in first place. Of course, we Cardinal fans knew it all along. We have complete confidence in our executives! Sure…

A secret movement is afoot to waive the current protocol and induct Shohei Ohtani into the Baseball Hall of Fame next week. One headline announced that Ohtani had been visiting the Dodgers’ bullpen to meet the guys. Word is out that he may add part-time pitching to his role as a DH.

The Miami Marlins lead the National League East, and the Braves are last…no surprise there.

At least 100,000 baseball writers have commented that “it is a long season.”

It is a long season!

AND

The Razorbacks are first in the mysterious RPI! They have finally passed Xavier, Texas, Rio Grande Valley, and yes, Tennessee. The three wins over Vanderbilt were the Hogs’ first sweep of the Commodores since 2005 and the first sweep in Nashville since 1994.

Nope, as usual, there is nothing new in baseball.

By the numbers

Last week in our Tuesday evening “meeting,” Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame historian, Jim Rasco, and I were talking about numbers. Since he is an accountant, that should not come as a surprise. The surprise is that there are a lot of quirky things about baseball numbers, and some interesting facts about the numbers worn by Arkansas guys.

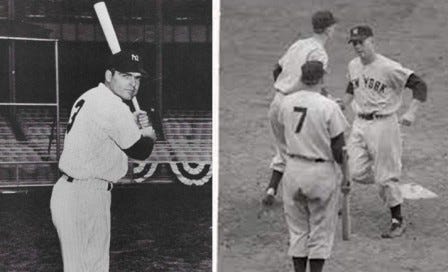

Of course, the Yankees have the most retired numbers. They have retired two numbers worn by outfielder Cliff Mapes. Mapes wore number “3” before the Yanks retired Babe Ruth’s number in 1948. Mapes was wearing “7” when New York promoted the kid from Oklahoma. The Mick wore “6” during his first call-up to the Yanks.

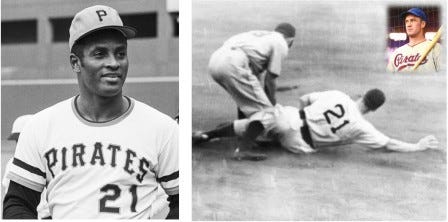

George Kell, who is primarily known as number “21” also wore “3” in his time with the Baltimore Orioles.

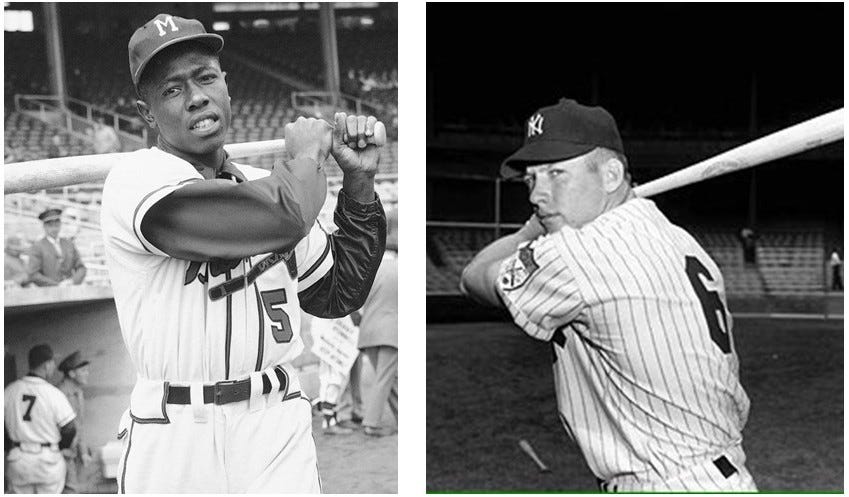

Hank Aaron wore number “5” early in his career, and Mickey Mantle wore “6” in 1951. Most Arkansans know Brooks Robinson wore number “5,” but Brooks also briefly wore “6” in his 15 games for the Orioles in 1956.

Kell’s “21” was also worn by Arkansas’ Hall of Famers Arky Vaughan and a guy in Pittsburgh named Clemente.

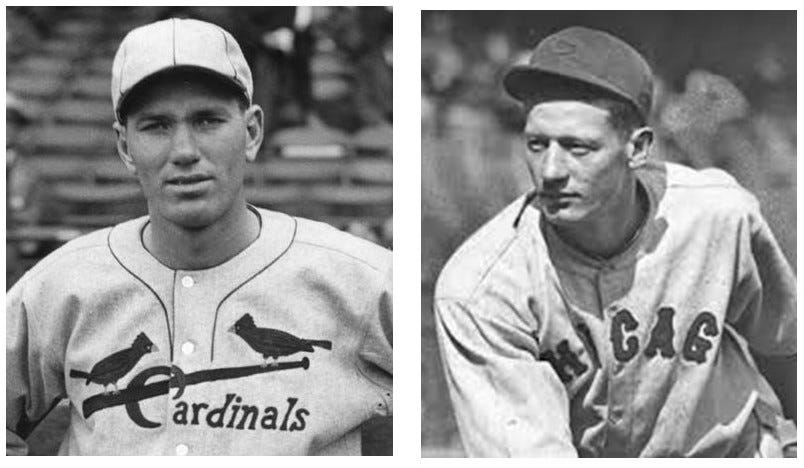

In 1932, a rookie pitcher from Arkansas named Dizzy Dean won 18 games and led the National League in innings pitched. Another Arkansas native, Lon Warneke, won 22 pitching victories and led the league with a 2.37 ERA. Was it a coincidence they both wore the number “17”? Warneke changed to “16” the next season and never wore “17” again.

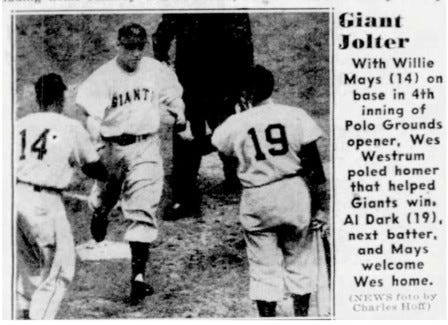

By the way, just as Mantle was not always “7” and Aaron wore “5” before “44” Willie Mays wore number “14” early in his career.

The Travs Return: 1916 and Beyond

After a going-out-of-business sale created an unfortunate interlude without pro baseball in Little Rock, Robert Allen, Ray Winder, and Judge William Marmaduke Kavanaugh revived the franchise in 1915. Although the year would begin in celebration, in February, the Travs lost their tireless advocate when Judge Kavanaugh succumbed to acute indigestion and died at his home. The season on the field was also disappointing.

The new team quickly dropped to the bottom of the standings and finished last in the eight-team league, 26 games out of first place. Allen managed the team until May, when he reassigned himself to run the business end of the franchise, look for a more capable field general, and find better players. By the next season, he had found some, and others had found him.

Baby Doll

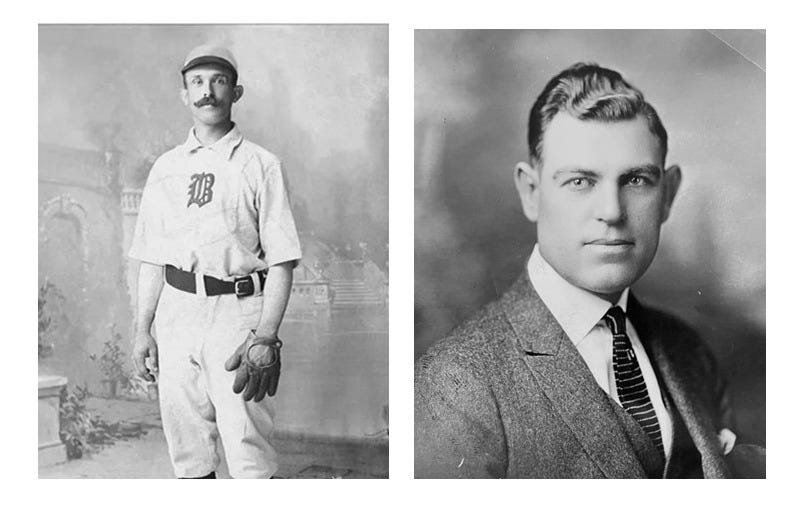

Perhaps the most surprising of Allen and Winder’s finds was an out-of-luck ex-major leaguer named William Chester Jacobson. In dire need of a second chance, and tagged with a less than respectful nickname, the outfielder they called “Baby Doll” had seemed overmatched in 1915 when he played in 71 major-league games for the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Browns. At age 24, after more than 460 games in the minor leagues, time was running out for the big outfielder to either prove he was a major league prospect or to settle into a career on the backroads of professional baseball.

Jacobson was hitting .215 when the Tigers gave up on him in August of 1915. Detroit traded him to the Browns, where his .209 batting average the remainder of the season convinced no one he was ready for the big leagues. St. Louis was happy to send him down to Little Rock for the 1916 season with the option to recall him later. An option that the Browns probably never planned to use.

Baby Doll’s one summer in Little Rock would answer the question of his future in a resounding fashion. From day one, he was the centerpiece of the Travelers’ lineup. The club started slowly, but in mid-July, the Travs went on a rampage. The Travs won 15 of 22 games during one three-week surge and moved from seventh place to the first division. Down the stretch, Baby Doll Jacobson was the Southern Association’s best hitter.

Jacobson led the league in batting average, hits, and triples for the 1916 season. The Travelers got as close as third place, but Baby Doll’s bat in the middle of the lineup was not enough to catch a good Nashville team. Little Rock eventually finished in fourth place, a game behind third-place Birmingham. The following January, as expected, the Browns promoted Jacobson to the major leagues.

In 1917, at age 26, Jacobson became the St. Louis Browns’ everyday center fielder. Unfortunately, just as his career had started in the right direction, Jacobson spent the entire 1918 season in the Navy. When he returned to the Browns’ lineup for good in 1919, he began an eight-season run as one of major league baseball’s leading hitters and an outstanding defensive outfielder.

From 1919 to 1927, Jacobson batted .315. He was among the league leaders in doubles and triples four times and finished in the top ten in the MVP voting in 1924 and 1925. Defensively, he led the league in putouts by a center fielder three times, including a major-league record 488 in 1924, a mark that stood until 1948. Six times he was in the top ten in fielding percentage at his position.

Baby Doll Jacobson played his last major league game on September 22, 1927. After two years in the minor leagues, he retired to his home in Orion, Illinois, where he remained until he died in 1977.

Occasionally, Jacobson’s name appears on some lists of players overlooked by the Baseball Hall of Fame, but an objective evaluation of his career record does not reveal Hall-of-Fame credentials. Baby Doll Jacobson was, however, one of the outstanding players of his time and the first star for a franchise in dire need of a quality player.

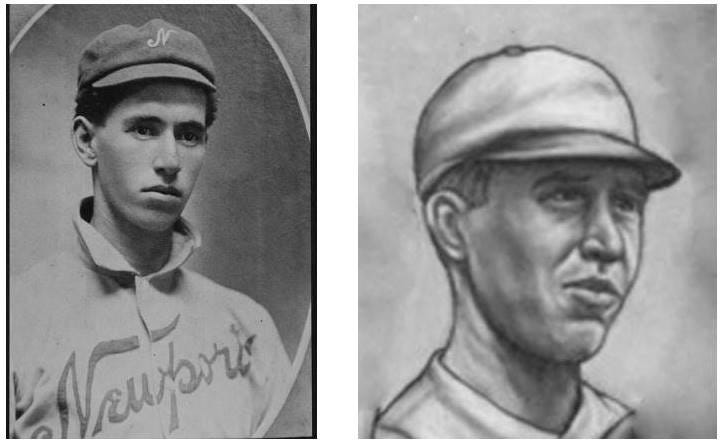

Rube

Robert Allen and Ray Winder get some approbation for finding a big-time outfielder like Baby Doll Jacobson on the scrap heap of major league baseball. They get less credit for signing a farm boy from White County who would eventually become the most successful pitcher in Little Rock Travelers’ history.

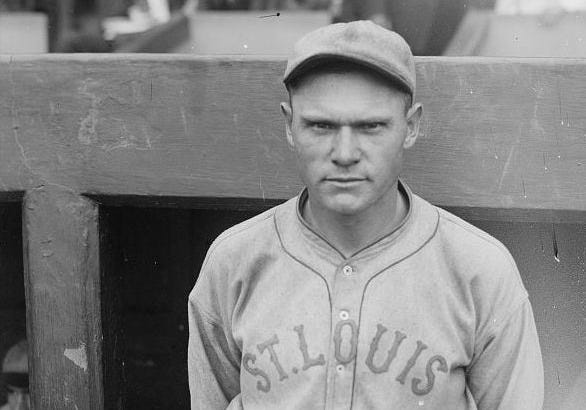

John Henry Roberson was so adamant about pitching in Little Rock that in 1916 he packed his bags, left the Cardinals, and declared himself a free agent. Known locally as Rube Robinson, a nickname he acquired pitching for Argenta in about 1908, the big lefty from Floyd, Arkansas, managed to become a “free agent’ whenever he tired of city life.

By 1916, “Rube Robinson” was in his eighth year of pro baseball. He had proven himself in Pittsburgh, but he did not like the idea of playing in the big cities back East, nor a contract that made him the property of a major league team. Perhaps being “owned” by a big league team was second on his “dissatisfaction list” to his feelings that he was mismanaged by the Cardinals.

Robinson had been comfortable with his original major league team, the Pittsburgh Pirates, but the Cardinals tried to use him as a relief pitcher on off-days, a plan that resulted in a sore arm that bothered Robinson most of 1915. He did not post a pitching victory after July 31, and sports writers began hinting that they had been wrong to predict he was a quality big league pitcher.

In January 1916, the Cardinals assigned their sore-armed lefty to San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League. In a move that should have surprised no one, Robinson remained in Floyd. Citing a somewhat sore arm and dissatisfaction with the terms in San Francisco, Robinson declared he would pitch only in Little Rock or for a White County semi-pro team. Other teams need not apply.

Thus continued the saga of a major-league-quality pitcher who simply refused to pitch where assigned if it did not meet his wishes. His arbitration strategy was unique and effective. As in the past, if a team purchased or traded for his services, he would simply refuse to go. Robinson soon convinced the Cardinals that he was not bluffing. He remained in Floyd, worked his sore arm into shape, and sent word to the Cardinals that he would only pitch in Little Rock.

Robinson’s arm had fully recovered by mid-July, and his staunch refusal to play anywhere else prompted the Cardinals to assign him to the Travelers. Little Rock got the Rube Robinson who had been one of the best left-handed prospects in the majors, not the sore-armed, ineffective Robinson of the last two seasons.

He won five of his first six starts with the 1916 Travs. The Cardinals exercised their option to recall Robinson in August, but he would not go. He remained in Little Rock and posted an amazing 11 - 1 record from July 15 until season’s end.

By November of 1916, the Cardinals were further convinced Robinson was not coming back to St. Louis. They sold his rights outright to Traveler’s owner Robert Allen. For the next 13 years, the Travelers would benefit from the services of a major-league-quality pitcher who would rather play for less and remain near his Arkansas home.

In 2018, I worked with Caleb Hardwick, the administrator of the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia, and Mark Williamson, an SABR member and expert on the Northeast Arkansas League, to recalculate the number of pitching wins Rube Robinson had accumulated in his pro career.

After months of tedious research, we agreed on a career total of 329 pitching wins. That total makes Robinson (John Henry Roberson) (Hank Robinson, BaseballReference.com) the career leader in wins as a professional among Arkansas-born pitchers. Link

_________________

A Subscription sends the weekly post to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link

Rub Robinson story 👍!

I'm glad Brooks Robinson switched to 5, because George Brett (who chose that number in part as a tribute to Brooks) just wouldn't have seemed right as number 6. Brett also wore 25 his first couple of years in the majors.