Backroads and Ballplayers #38-Taking the Big Leagues by Storm

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Note: Important access to this weekly post: There are three ways to be sure you receive this column/blog.

Subscribe, always free.

Remind yourself each Monday evening to look for the post on my Facebook.

Email me directly. Link

The Changing Game

The response to my Ohtani math endeavor from BRB #37 was lots of fun. In summary, all perspectives see him as a generational talent, doing remarkable things, and good for baseball. The difference of opinion is based on evaluating him based on cumulative accomplishments, or never-before-seen short-term performance. I am still in the “wait and see” group. I like him very much, but I am still not sure if he is Ruth, Mays, Williams, or even Big Papi.

To move on to pitching in the “changing game” discussion, do you remember shutouts and complete games? I expect that those two will disappear soon from the categories listed prominently on Baseball Reference.com. Last year Gerrit Cole and Framber Valdez tied as American League leaders in shutouts with two. Sandy Alcantara and nine others shared the National League “title with one each.

Alcantara also led the National League hurlers in complete games with three. American League leader Jordan Lyles also pitched three complete games. Lyles led the league in losses and had a 6.28 ERA. Contrary to the historical significance of a complete game, Lyles lost all three of his complete games.

Cy Young winner Blake Snell has never pitched a complete game.

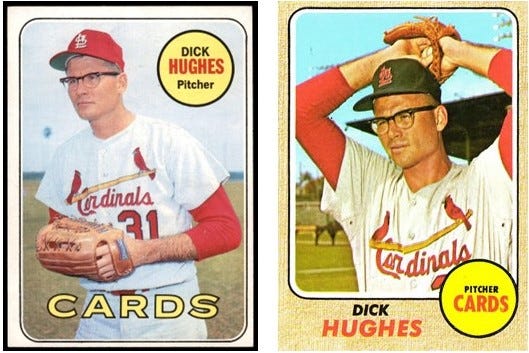

Dick Hughes Magic Summer 1967

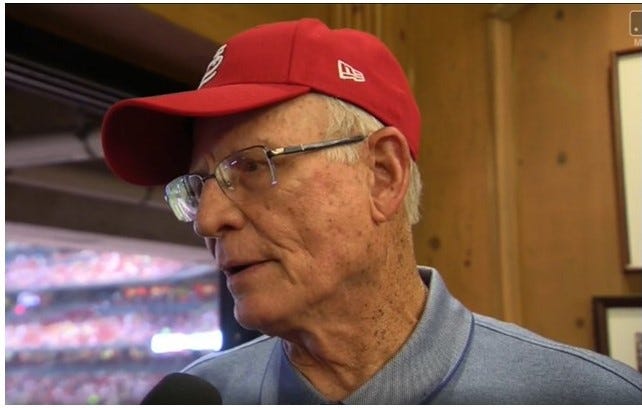

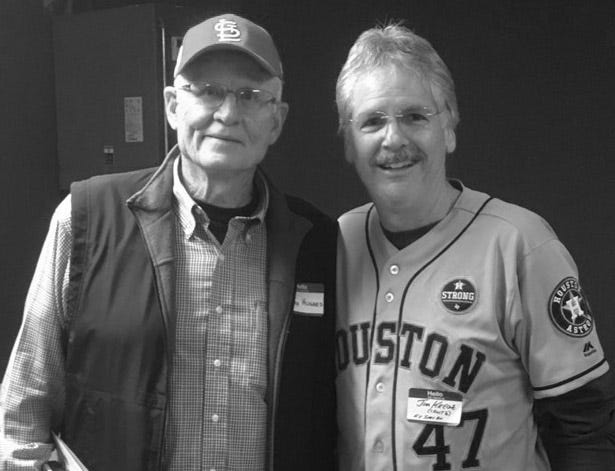

On April 16, 2022, Richard Henry Hughes threw out the ceremonial first pitch in the Razorbacks’ 6–2 victory over LSU. Just over 11,000 were at Baum-Walker that day. Many were hearing for the first time the remarkable accomplishments of a 1967 rookie named Richard Henry Hughes. Those in the crowd old enough to have “seen it on the radio,” knew the story very well. In the Cardinals country of 1960s Arkansas, the Cardinals Baseball Network ruled the airways.

The 1967 Cardinals were seldom on television, but Harry Carey and Jack Buck described the tall bespectacled Arkansas farm boy who leaned forward looking for a sign as if he could not see the catcher. Harry and Jack said he was amazing—that career minor leaguer who had arrived the fall before from somewhere in the Cardinals farm system and became the best pitcher in the game. Dick Hughes had taken 10 years to become an overnight success.

Hughes was born in Stephens, Arkansas, on February 13, 1938. His family followed his father’s job with the Tennessee Valley Authority to Shreveport, Louisiana, after World War II where young Richard was a high school pitching star at Byrd High School. His former teammates had to think twice to realize the amazing rookie of 1967 was their classmate from 1956. “But even under a different name—Hughes never changed much from the kind, humble kid who classmates claim could “play the guitar, and throw a baseball as good as anyone.”

According to Thomas Van Hyning, Hughes’ biographer in the SABR Bio Project, St. Louis Cardinals’ scout Fred Hawn recommended Hughes to Bill Ferrell, baseball coach at the University of Arkansas. Ferrell was known best as the trainer for the football team, but he also coached the baseball team.

In addition to his notoriety as a coach and trainer, Ferrell was credited by insiders at U of A as the man who saved Dick Hughes’ life. On a late-night road trip back from Mississippi in April of 1958, the car driven by Ferrell collided with another vehicle somewhere between Little Rock and Alma. Only Ferrell’s legendary strength kept the car upright. According to Hughes, Coach Ferrell, “. . . bent the steering wheel in his hands,” holding the car on the road. Hughes and the other players in the car were uninjured.

Hawn, who lived in Fayetteville while scouting the southwest for the Cardinals, kept an eye on Hughes. In 1958, the summer after his sophomore year, the scout arranged for the 20-year-old to attend a tryout camp in St. Louis. According to Hughes’ recollection of the tryout, “I struck out every guy I faced.” The impressed Cardinals signed the 20-year-old to his first pro contract. During the next eight seasons, Hughes made a circuitous journey through the various destinations in the Cardinals’ farm system but never made a trip to St. Louis.

In 1958, he pitched four games for Keokuk, Iowa, in the Midwest League, and three for Winnipeg, Manitoba, in the Class C Northern League. He returned to Winnipeg in 1959 and posted a 10–3 record for the league champ Goldeyes. Hughes was the winning pitcher in the final game in the Northern League playoffs. That 1959 Winnipeg championship squad was inducted as a team into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame 60 years later.

In 1960, Hughes led Tulsa to a Texas League playoff title. He won seven straight games down the stretch and his 3.71 ERA was the best among the Oilers’ starting pitchers, but Hughes’ seemingly routine journey to St. Louis bogged down in 1961.

Beginning with the arrival of Bob Gibson in 1961, the talent in the Cardinals’ farm system began to pay dividends, but Dick Hughes’ rise to the big league had lost momentum. From 1962 through 1965, Hughes won 34 pitching decisions and lost 23, with a 3.32 ERA—acceptable marks, but not attention-getting. He remained in the high minors while younger Cardinals prospects like Steve Carlton, Nelson Briles, and Larry Jaster were promoted.

Hughes began to make some plans for life after baseball. He had married Anne Wreyford, a graduate of Southern State University, in 1964. He and the new Mrs. Hughes had saved enough from his minor league salary and some winter-league work to start a cattle operation with his father in Ouachita County. Hughes thought he still had major-league stuff, but, realistically, he must have wondered if he would ever get the chance. The turning point in his career occurred in a flurry of promotions in 1966.

After starting the 1966 season in Tulsa, Hughes moved to Little Rock in mid-May. He was outstanding in a brief stay with the Travelers, striking out 43 batters in 41 innings and posting a 2.35 ERA. In some mysterious arrangement, the Cardinals “sold” Hughes to the triple-A Toledo Mud Hens on June 19.

If a clandestine clause in the sale allowed the Cardinals to change their mind, Little Rock manager Vern Rapp did not seem to be aware of the details. Reacting to Hughes’ excellent start in Toledo, the Arkansas Gazette quoted Rapp’s prediction that “he might be pitching in Yankee Stadium before the season is over. He looked like he had found himself before he left here.” Rapp was somewhat correct. Hughes would be promoted to the parent club in September, but that team was the St. Louis Cardinals.

Whatever Hughes found in Little Rock elevated him to the Cardinals’ prospect list in a matter of weeks. In 17 games for the Mud Hens, Hughes won nine decisions and lost four. He struck out 132 batters in 110 innings and posted a 2.21 ERA. In early September, he packed his bags for the fourth time. On that trip, he met the Cardinals in Pittsburgh. After nine years and eleven uniform changes, things were looking up for Dick Hughes. The new Cardinals’ pitcher described his minor league travels as “. . . a long fight with a short stick.”

Hughes was the winning pitcher in his major league debut, a relief appearance on September 11, and he ended the month with a complete-game shutout on September 30. In his six games with the Cards, Hughes pitched 21 innings with a 1.71 earned run average, setting the stage for his historic rookie year in 1967.

Cardinals fans and sportswriters, tired of the same stories, loved the arrival of a country personality like Dick Hughes, and he obliged them with some of the Arkansas folk wisdom they expected. Quick to think but slow to speak, the sagacious Hughes made good press. When asked if he thought he would be nervous facing a Pittsburgh lineup with hitters like Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente, Hughes replied, “I really try not to think about not thinking about being nervous.”

Hughes had pitched well in his late-season trial with the Cards the previous fall, and, as expected, he made the 1967 Opening Day roster. He was finally in St. Louis, but the Cardinals had no plans to make him a part of their regular starting rotation. With Bob Gibson, Larry Jaster, Nelson Briles, Ray Washburn, and veteran Al Jackson slated to be the starters, Hughes was used in relief.

Hughes pitched five times in April, all in relief. Although saves were yet to become an official part of baseball statistics, he finished three games and two were retroactively recorded as saves. His April ERA was 2.35. As the season moved into June with the Cardinals in a tight pennant race, manager Red Schoendienst decided to make a pitching staff adjustment. He moved Al Jackson to long relief and made Dick Hughes a starting pitcher.

Hughes won five straight in June including a complete-game three-hitter over future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry in San Francisco. The win moved the Cards into first place, a position they never relinquished for the remainder of the season.

At the time Red Schoendienst moved Dick Hughes to the starting rotation, the Cards were two games out of first place and Hughes had won three games and lost two. When the National League season ended on October 1, Hughes had won 16 games and lost 6 to lead the Redbirds who had outdistanced the rest of the league by ten and a half games.

Along the way, amiable general manager Stan Musial called Hughes into his office on two occasions to give the Cards’ new pitching ace a raise. After all, the rookie sensation was leading the team in wins, innings pitched, complete games, and shutouts. Hughes had a better ERA than Steve Carlton, more strikeouts than Bob Gibson, and an 8–1 record vs the Giants, Cubs, and Phillies, clubs that were in the pennant race all summer.

Although he did not pitch well in his two World Series starts, Dick Hughes had produced one of the most celebrated rookie seasons in Redbird history. Tom Seaver was chosen by sportswriters as National League Rookie of the Year, but the Sporting News award for National League Rookie Pitcher of the Year, selected by player vote, went to Dick Hughes.

When the Cardinals’ first salary offer tied his new contract to the number of pitching wins he might produce in 1968, Hughes politely thanked the team for the confidence but declined. Back in Arkansas, folks do not gamble with their future income. A raise to $25,000 would be just fine.

With his World Series share, he and Ann bought some cows and a used farm vehicle. Hughes’ only extravagance was a new deer rifle, which he carried over his shoulder on the team plane. His teammates called him “the sniper.”

Although he had a good spring training in 1968, Hughes knew something was not right with his pitching shoulder. The persistent pain, first diagnosed as tendonitis, was later determined to be a torn rotator cuff, a career-threatening injury in 1968.

Armed with courage and persistence, Hughes had an acceptable 1968, but far below his and the Cardinals’ expectations. He gave up six runs in less than two innings in his first start. By May, he was pitching in constant pain, and his ERA was ten runs per nine innings.

He only made seven appearances from June 1 to August 1, but, with more cleverness than velocity, he pitched well down the stretch. In ten games in August and September, Hughes pitched 28 innings and allowed only six earned runs. His final totals for 1968 were a 2–2 record, 63 innings pitched in 25 games, and a 3.53 ERA.

The Cardinals left Hughes in Florida when the team moved north in April 1969. He pitched effectively for 15 games for St. Petersburg in the Florida State League, but the reality of constant pain brought him home to Stephens before the end of the season. His pro baseball career was over but not his life.

Dick and Anne started a new routine back in Arkansas beginning in 1970. She became a beloved English teacher at Stephens High School, and he became a cattle farmer and part-time baseball scout. Every Sunday, the couple, whose photos once appeared at the top of the sports pages, could be found simply being Dick and Anne at the First Baptist Church of Stephens.

On February 3, 2018, Dick and Anne Hughes were the guests of the Robinson-Kell Chapter of SABR in Bryant, Arkansas. After an hour and a half of baseball stories, well told, the Hugheses volunteered a favorite song they had not only sung often but lived their life by. In a well-practiced performance, the couple offered their philosophy in the hymn, “One Day at a Time.”

If you have missed some posts click here: Link to access past posts.

More of my stories in Only in Arkansas

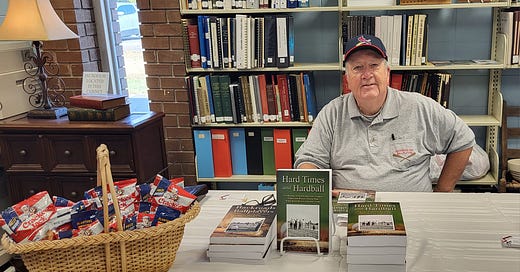

If you want signed Hard Times and Hardball or Backroads and Ballplayers: Ordering instructions Link