Update 1-9-2025

Best Wishes for 2025 and a Happy Snow Day

This week, in my Monday post I reflected on 2024. I was asked to choose the my favorite story and my favorite Substack post.

Below is the post from May 6, 2024. This post has been read by more than 800 individuals. My trip to Johnson County was a special evening for Susan and me and my favorite Substack post of 2024.

Town Teams Part I Watching Leroy

Lost Stories: Town Teams Part I

I spent an amazing evening last week at the Johnson County Historical Society. My favorite part of my “work” on the baseball history of our state, is hearing what I call the “grandpa stories.” I love the memories of the men and women who grew up in a time when baseball was “Arkansas’ Game.” Some of my favorite of these “lost stories” originate in Johnson County.

Some of you may be old enough to remember when the newly developed Interstate Highway system funneled America’s coast-to-coast travelers through the Arkansas River Valley. One of the last incomplete sections brought a steady stream of travelers through Ozark, Arkansas.

In Ozark, we could listen to the Cardinals on our transistor radios. We received a single TV station that carried one major league game each week…and we had the “town team.”

On Sunday afternoon, my dad loved to sit on a bench at the Milam’s Lion Oil station and watch the “variety” of America’s travelers pass through our sleepy little town. He would drop me off at the ballpark on the east side of town to watch a local semi-pro team called the Dixie Blues. The Ozark town team was pretty good. I thought they were great. In my 14-year-old evaluation, the collection of college-age players and hometown guys were just short of major leaguers.

Watching Leroy

The Dixie Blues had players from the College of the Ozarks, and Arkansas Tech as well as some locals in their 30s who had been playing on town teams for several years. One of the veterans was obviously different, even to a kid who had never seen a professional team play.

The player who caught my attention was Leroy Douglas, and he looked a lot older than some of the Blues. I think he was 28. Douglas was the basketball coach at Coal Hill High School about 10 miles down the road. He was the Dixie Blue’s ace pitcher and when he wasn’t pitching, he played first base. The story around the ballpark was that he had once been a major-league prospect before getting hit in the head in the minor leagues somewhere. I thought that was a good story, but judging by the reputation of the tellers, I decided it probably lacked any basis in fact.

Douglas was a right-handed pitcher who had a decent fastball and a lot of other stuff that left the opposing hitters shaking their heads. He batted left, and he hit those line drives that hooked left to right like a tee shot. I have a vivid memory of one of those. It was still about 10 feet off the ground when it crossed US 64 somewhere near Gar Creek Park.

After I reached high school, he became the junior high principal in another building. I saw him every day. He was tall and athletic-looking, but the town team no longer played on those Sunday afternoons, and I never saw him play again. I had my own games to play.

As I grew older, I never lost my love for baseball. I thought a lot about how enamored I had been watching that team of men in my hometown. I also thought about Leroy Douglas. When I wrote my books, I did not research Douglas. I had filed away my memory of the Dixie Blues, as the misplaced infatuation of a kid.

That changed about a year ago when I received an email from a lady named Lori Weathers. Mrs. Weathers is a teacher in the Clarksville School District and the daughter of Leroy Douglas. Did I have any information about her dad?

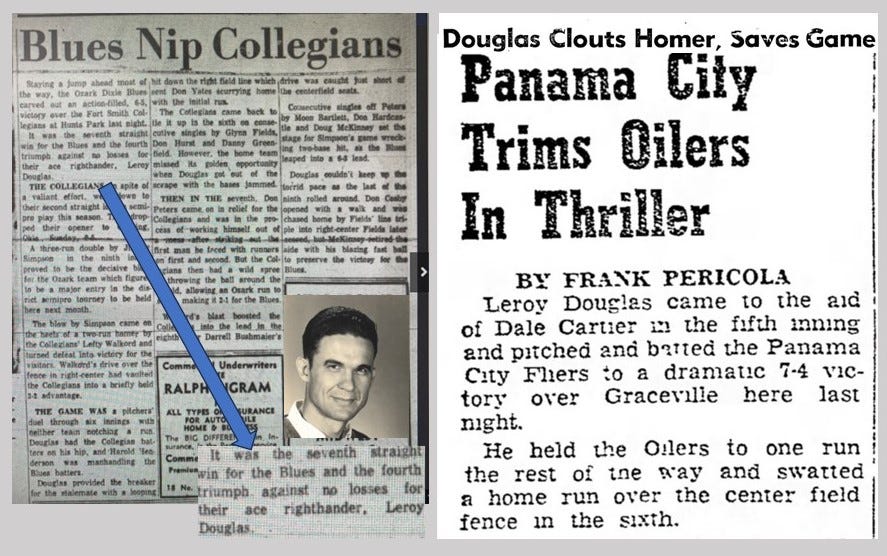

My research that day started with a newspaper search. To my surprise, Leroy Douglas was indeed one of Arkansas' most acclaimed baseball players in the early 1950s, and the ballpark tale of his career-ending injury was true!

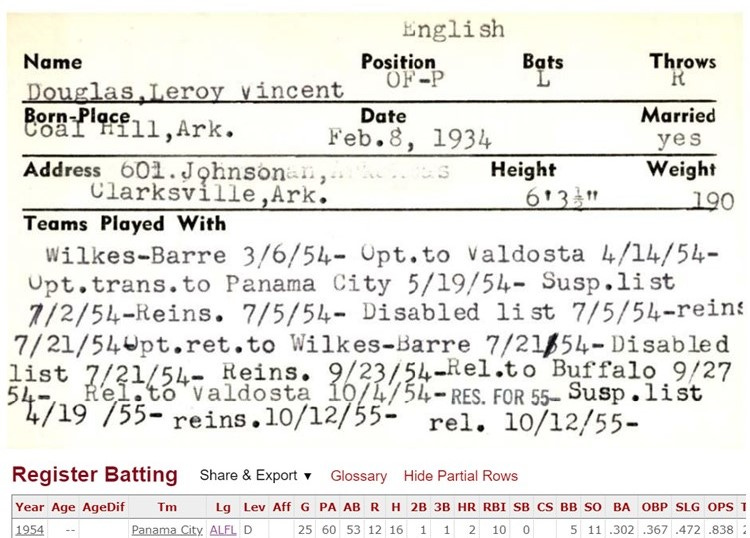

As a freshman in 1954, he was an All-Conference pitcher and .481 hitter for what was then the College of the Ozarks. The Detroit Tigers offered him a $4,000 bonus, and by age 20, he was playing minor league baseball in Valdosta, Georgia.

The Tigers obviously had not decided if he was an outfielder or a pitcher, so after a month in Georgia, Detroit reassigned him to Panama City, Florida. In his new assignment, he played outfield on the days he didn’t pitch, a pretty bold experiment for 1954.

The plan worked with one small flaw. He was exceptional at both. As spring moved to summer Douglas was 3-0 as a pitcher, and he was batting .300+ with two home runs and 10 RBIs in 10 games as a pitcher and another 15 in the outfield. Almost seventy years before Shohei Ohtani, a young minor leaguer from Coal Hill, Arkansas, was proving that pitchers could play successfully on days they were not on the mound.

On July 2, Panama City announced that Douglas would be placed on what was then called the “suspended list” due to a probable concussion. As indicated on this data card above, Douglas attempted to play again on several occasions, but he never played another professional game. The ballpark story that followed Douglas to the Ozark town team was true.

Leroy Douglas was officially released in October 1955, but he eventually recovered from his injury to become a semi-pro star in Western Arkansas. First with the Fort Smith Smokies and later the Ozark Dixie Blues, Douglas was one of the most outstanding players in the region.

At least three times he was named to the All-State Semi-Pro team by the National Baseball Congress, and in 2004, Leroy Douglas was inducted into the University of the Ozarks Hall of Fame. He holds a special place in my baseball life, a place reserved for hometown heroes.

Thanks for the memories!

Thanks to Bronson Ruston and Lori Douglas Weathers for their contributions to the Leroy Douglas story.