Backroads and Ballplayers #90

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Link to: Spring Training Countdown

Arkansas’ Team and a Lost Dizzy Dean Story

A few thoughts about the St. Louis Cardinals.

“I was raised as a coach's son and I was a baseball player back in Arkansas, [ ]So that's what I was going to do: Pitch for the St Louis Cardinals” —Billy Bob Thornton

As we count down to another baseball season, I usually share some version of this story about Arkansans’ affection for the St. Louis Cardinals.

Sometime in the mid-1950s, I decided I was a Yankee fan. My buddy Johnny Carpenter picked the Dodgers, and my Midget League teammate Bob Anderson chose the Braves. Those decisions may have been influenced by our chosen teams being three of the most successful major league franchises of our childhood. They also appeared on the Game of the Week TV schedule more than any other teams.

Every adult I knew was a St. Louis Cardinals fan.

In the summer of 2018, Susan and I made a quick trip up to St. Louis to catch a Cardinal Baseball game. The Cards were fourth in a five-team division and it was a Tuesday evening. On that weeknight, with a team going nowhere, the Cardinals drew 43,000 fans to Busch Stadium. Despite finishing in the middle of their division, and not making the playoffs, the Redbirds would draw more than three million fans that summer and finished second in major-league attendance.

My first book would be published that fall, and I had yet to write an introduction. However, I had done a lot of thinking about Arkansas’ love for the St. Louis Cardinals.

I received a transistor radio for Christmas in 1959. It was about hand-sized, had a leather case, and operated on a battery that I soon realized needed a backup ready for an emergency transplant. Some of my first radio memories were of a loud, heavily-accented voice, proclaiming that I was listening to the “Cod Nal Baseball Network.” In the daytime, that network arrived in the Ozarks via KWHN in Fort Smith, and in the evening, from KMOX in St. Louis.

The distinctive voice on that broadcast was Harry Caray, one of the most iconic baseball broadcasters in American radio history. His partner was the equally unique and celebrated Jack Buck. The Cardinals were not my chosen team, but they were the only game available on my radio in Ozark, Arkansas. I followed every game while claiming to be a Yankee fan. Like millions of my generation, I loved Mickey Mantle.

What is it about the St. Louis Cardinals that unquestionably makes them the chosen team of a majority of Arkansans? Some of it is a historical and cultural confluence of several factors from the first half of the 20th century.

Arkansas was basically a rural state for much of the early 1900s and baseball was part of the summer routine. Three acres, a ball, and a bat were all it took to play, and every community had a town team. Arkansans from this era grew up in hard times. They endured a world war, a pandemic, a historic flood, and a great depression. Baseball was an escape and they loved the game.

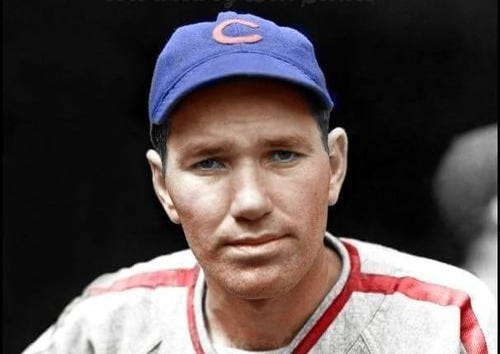

By the 1930s, new and exciting technology brought baseball into their homes. Radio took them to the stage of the Grand Ole Opry and Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, places most would never see in person. They identified with the mountain music and they connected with the baseball team playing in St. Louis. Especially, since two of the most famous stars on those early 30’s Cardinal teams were Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean and Paul “Daffy” Dean, from Logan County, Arkansas. The Cardinals had won World Series Championships in 1926 and again in 1931, but the 1934 season would be the ultimate event in the romance between Arkansans and the St. Louis Cardinals.

The rowdy, impetuous, and talented 1934 version of the Cardinals was tagged with the nickname, “Gas House Gang.” Their accomplishments and rough-and-tumble ways endeared them to their 1930s fan base and secured their place in Cardinal history. They scrambled to the pennant on the last weekend of the season with the Deans winning the last three games. Our great-grandparents were listening, and Arkansas was indeed Cardinal Country.

The 1934 World Series between the Gas House Gang and the Detroit Tigers was billed as the matchup of Arkansas pitching stars, and the first three games played exactly on script, with Dizzy Dean, Schoolboy Rowe, and Paul Dean trading pitching victories.

Unfortunately for Rowe, his win took 12 innings and 132 pitches to come to a 3 – 2 conclusion. He was never as sharp the remainder of the series and the Cardinals prevailed in seven games, with Dizzy Dean pitching an 11–0 shutout in the finale. The Gas House Gang had finished the dream season and caught the imagination of baseball fans everywhere, perhaps nowhere more than in the home state of the Deans, and Schoolboy Rowe.

Few Arkansas fans saw the Gas House Gang in person, but they talked about them like they knew them personally. The games and their conversations about them helped Arkansans through some tough times. They never saw Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, but they imagined what it looked like. It was green and symmetrical, not unlike the converted cow pasture where they played on Sunday.

In the 1940s, Cardinal fans, including those in Arkansas, fell in love with a line-drive-hitting first baseman named Stan Musial. Stan “The Man” played more than 3,000 games as a Cardinal and remains the most beloved Red Bird of all time. He helped Cardinal fans through a world war and teamed with a hard-nosed throwback named Enos “Country” Slaughter to win three World Series.

Some tried to copy Musial’s batting style, left-handed, in an awkward slouch, with his bat pointed straight up. They had seen it on the radio. Our grandpas told us about Musial’s heroics and Slaughter’s mad dash from first base to score the winning run in the 1946 World Series. After all, they were there, listening on the radio.

I met Slaughter once. Back in my baseball card shop days, we were vendors at a weekend sports card show in Tulsa. Enos Slaughter was the special autograph guest. On Sunday morning before the show opened, he walked down the aisles visiting the vendor tables. “Got anything I need to sign,” he asked as he chatted with Susan and me. “No, we had you sign a few things yesterday.” “Do you have a picture of me scoring from first base in the World Series" he added as he strolled away. “By the way, I am asking folks to help me get into the Hall of Fame,” was his departing line at each table.

In an earlier post, I told the lost story of the St. Louis fans’ cold reaction to the Redbirds trade that resulted in Wally Moon replacing the beloved World Series hero. In case you missed the Wally Moon story

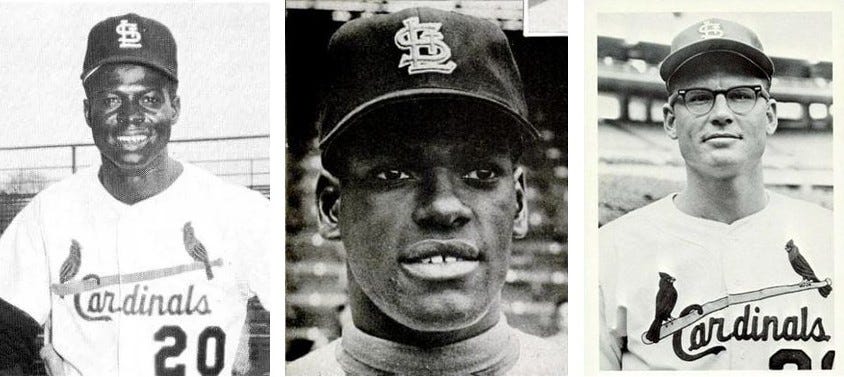

The 1960s radio generation did not have to see Lou Brock steal 888 bases as a Cardinal. The radio broadcast vividly described the Arkansas native disrupting the opposition with his speed. They heard Harry and Jack describe Bob Gibson’s intimidating presence, before finally getting to see him win two championships on TV. In 1967, local fans celebrated Stephens, Arkansas’ Dick Hughes’ amazing rookie season. Forced into the rotation by injury, Hughes went 16-6 and was instrumental in the championship season.

Regardless of Arkansas baseball fans’ allegiance to today’s St. Louis Cardinals, the Red Birds are culturally and historically the Arkansas team. They are the team of our great grandfathers, and the legacy of baseball tradition found deep in the roots of our rural past. The stories are fading and somewhat muddled in the retelling. But they remain not only stories about baseball but also about our heritage.

Bob Gibson is the luckiest pitcher I ever saw. He always pitches when the other team doesn't score any runs. —Tim McCarver

__________________________________________________

I do pretty well on Cardinal baseball history. It is the current situation in St. Louis that baffles me. I rely on my bud Daniel to keep me informed. Take a look at his latest take on the saga of Nolan Arenado: Cardinal70 at bat!

Another lost story from 1937

I hope you read the story in Only in Arkansas about the amazing story of the 1937 Little Rock Travelers.

While that historic drama in Little Rock was playing out in the Southern Association, a tragic melodrama in St. Louis would be life-changing for Arkansas’ Dizzy Dean.

Dizzy’s Apology

May 19, 1937, was a Wednesday in St. Louis, but more than 26,000 fans called in sick or skipped school to see two of baseball's most popular country-boy pitchers face off in one of the hundreds of games the press would label the “game of the century.”

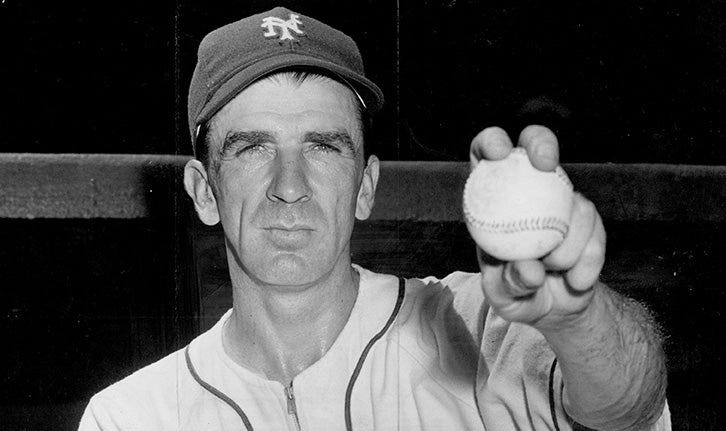

Carl Hubbell, the product of a pecan farm in Meeker, Oklahoma, had used an anatomically challenging screwball to win 21 straight decisions during parts of two seasons. His pitching opponent that day was Dizzy Dean, the epitome of a country hardball pitcher. Dean, the spinner of backwoods yarns, master of self-promotion, and hero of rural America was 5–1 with a minuscule 1.09 ERA.

The matchup at old Sportsman's Park between the Cards and the Giants was a classic. Dizzy Dean was on the mound trying to end the longest streak of winning pitching decisions in baseball history. “King Carl” Hubbell, the Most Valuable Player in the National League the previous season, was going for his 22nd consecutive win.

The game was exciting and emotional, but the lingering effects of that pitcher's duel in St. Louis were life-changing. The game began a series of associated incidents responsible for the tragic decline of Dizzy Dean’s career.

Diz got the early advantage when Ducky Medwick homered in the second inning. He allowed the Giants only two hits and two walks through the first five innings, and, entering the sixth inning, no New York runner had reached second base.

Dizzy was pitching as though the one run was all he needed. That changed quickly in the visitor’s half of the sixth inning. Burgess Whitehead led off the inning with a single to right, and Hubbell moved him to second with a sacrifice bunt. Dick Bartell lofted an easy fly ball to left field, but the second out was nullified when umpire George Barr called Dean for a balk on the pitch.

Dizzy protested vehemently, as did his manager Frankie Frisch, but to no avail. When the game resumed after the prolonged tantrums, Dean was shaken. An error scored one run, and two consecutive singles plated two more. When the Giants’ half of the inning mercifully ended, Dizzy and the Cards were down 3–1.

The ninth inning would produce another Giant run and feature a bench-clearing melee between the two emotional teams. The 4–1 Giant victory was a difficult loss for the Cardinals and an especially painful defeat for Dizzy Dean.

Dizzy Dean and the Cardinals awoke the morning of May 20 still fuming from the events of the day before. Dizzy and manager Frankie Frisch received scolding phone calls from National League President Ford Frick. Diz was also assessed a $50 fine for his outburst after the balk call and his part in the ninth-inning brawl. Although Umpire George Barr had called the balk, the weeks that followed the game moved the confrontation to a battle of words and wills between Dizzy Dean and league president Ford Frick.

The battle of wills reached a critical public turning point for the league president about a week after the balk incident. At a father-and-son banquet, Dean openly criticized Frick with comments that drew widespread newspaper coverage. Dizzy used the word “crooks” to describe the league president and the umpire who called the balk a few days earlier. At a time when organized crime was still an emotional issue in America, being called a crook was a slanderous characterization.

Above a newswire photo of Dizzy signing an autograph for a young fan, the headline read, “Dizzy Dean Assails National Loop President And Umpire Barr At Father-Son Dinner Here.”

Dean had taken the conflict to a new level, and the president reacted in a way that would soon place his office in a no-win position. On June 3, Frick announced that Diz was suspended until he made a remorseful public apology. “It is up to Dean if his suspension lasts for 24 hours or three months,” Frick said. “It’s got down to the question if Dean is bigger than the National League. I don't think he is. This could all be settled quickly if Dean sees the error of his ways and frankly apologizes to the league for the things he said or implied and puts it in writing.”

Ford Frick had taken a decisive stand, but Dean did not flinch. It would take some significant negotiations, mostly between the Cardinals and the league president, to find a way out of Frick’s ultimatum. The All-Star Game was just over a month away in the nation’s capital, and Dizzy Dean had publicly vowed not to pitch in the game. President Roosevelt would throw out the first pitch, and baseball needed Dizzy Dean.

The popular pitcher knew he was operating from a position of power, and he responded with three public threats: to quit baseball and spend the rest of the summer in Florida, to offer his services to semi-pro teams, and to call his wife. Perhaps Diz viewed the third alternative as the most serious.

The next day, the Cardinals persuaded their ace to participate in a phone interview that would allow Frick to save face. The two-hour session resulted in Dizzy's reinstatement but offered little in the way of a capitulation on his stance. “Well, I won my point, I said I wouldn't sign anything, and I didn't sign anything,” Diz stated proudly.

Now that some sort of truce had been called, the commissioner could call it an apology, and Diz could be the National League starter in the All-Star game. Although Diz had vowed to skip the All-Star Game, he couldn't pass up the opportunity to represent his fans and the Cardinals.

Dizzy Dean had the ball for the National League in the first three innings. He got off to a good start. It looked like Diz would cruise through his stint unscathed, but, after two scoreless innings and two routine outs, a pair of New York Yankee All-Stars gave the American League two runs on a DiMaggio single and a Lou Gehrig homer.

Thirty-five-year-old Cleveland Indian outfielder Earl Averill batted next and hit one of the most tragic groundouts in baseball history. The sharply hit line drive struck Dizzy Dean on his left foot and caromed to second baseman Bill Herman, who threw to first for the final out. A jubilant National League team celebrated their good fortune as they ran from the field, but Dizzy did not join the celebration. He could barely walk on what would later be diagnosed as a broken big toe on his left foot.

For the first few weeks after the injury, Dean and the team medical personnel refused to confirm the toe was broken. On July 21, Dizzy pitched a complete-game loss to the Boston Bees. Despite the 2–1 score, something was wrong. Dizzy’s delivery was awkward, and he had virtually no fastball. By now, even Diz was forced to admit there was a problem with the toe. To compound his frustration, his unnatural delivery had done irreparable damage to his arm.

Dizzy Dean won one game for the Cards in the last half of the 1937 season, and his 12–7 mid-season record deteriorated to 13–10. General Manager Branch Rickey, never known for sentiment, traded the Cardinals’ most popular player to the rival Chicago Cubs before the beginning of the 1938 season.

Dizzy tried valiantly to reinvent himself with the Cubs, and, although he pitched in constant pain and his arm was unable to produce anything that resembled a Dean fastball, he managed to win some big games. Despite his arm problems, Dizzy Dean’s pitching smarts were formidable, and his courage and resourcefulness, belied by his backwoods rhetoric, were easily overlooked. He pitched a total of 226 innings over parts of four seasons with the Cubs. He had averaged more than 300 innings a season during his heyday. After one ineffective inning in 1941, Dizzy retired at age 31.

The heartbreaking events that led to the premature end of Dizzy Dean’s career tend to be retold beginning with the All-Star game on July 7, 1937. While it was the most significant moment in the tragic saga, the Earl Averill line drive that broke Dizzy’s toe was preceded by a series of related events that, had they transpired differently, could have changed baseball history.

______________________________________

Link to Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. Save it somewhere if you do not feel comfortable subscribing. Look for a new post on Monday evening.

Currently, there are about 300 subscribers in our community. The biggest benefit for me is that I can email any subscriber personally to discuss our shared love for baseball history.

Please consider a free subscription to Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly. These posts will always be Free.

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Great Baseball stories!

I appreciate the link! Though my brother would be surprised to see his name attached instead. 😂