Backroads and Ballplayers #89

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Losing Mr. Baseball, An Evening with Tito, and the Miracle of ‘37

“The headline in the paper read Braves Swap Bob Uecker for 2 Cards, …but at least one of those was a Bob Gibson card.” —Bob Uecker

If you find yourself in major league baseball without the necessary talent to be a star, how do you become a beloved part of the history of the game? In the case of Robert Charles Uecker, you tell stories, funny stories about the colorful guys you played with and against, and especially self-deprecating stories about yourself.

Bob Uecker was a broadcaster, actor, after-dinner speaker, comedian, and a good enough baseball player to play about 300 games in the major leagues. He was a recipient of the prestigious Ford Frick Award presented by the Baseball Hall of Fame for excellence in broadcasting.

Uecker was playing in the big leagues when I was a youngster, and he was an iconic ambassador for the game during my adult years. He will be greatly missed.

If you have 15 minutes and fond memories of Bob Uecker, you will love his acceptance speech when he received the Ford Frick Award for baseball broadcasting. Baseball was the only way I wanted to go.

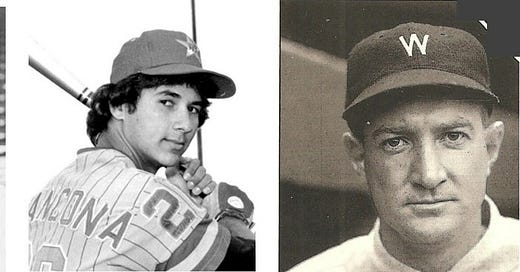

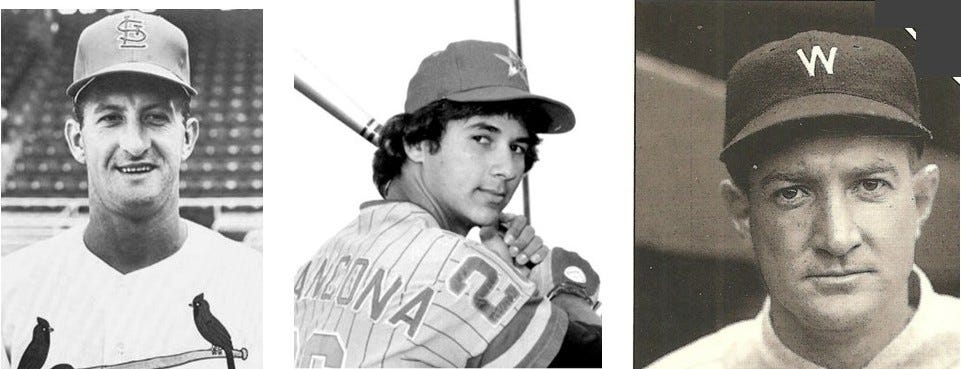

Talking Baseball with Terry Francona

Saturday evening with the Chiefs in a tug of war with the impertinent Houston Texans, Arkansas Tech held a kickoff event to their baseball season. Despite the NFL alternative, there was a full house in the ATU baseball facility to hear Cincinnati Reds manager Terry Francona.

Sometime in the upcoming season, Francona will win his 2,000th game as a manager. He has won three pennants and two World Series titles, but Francona will always be known as the manager who broke the “Curse of the Bambino.” That alone should headline a Hall of Fame resume.

Francona had some prepared notes, mostly for the Tech players in attendance, but he was at his best sitting on a stool and answering questions for most of an hour after he finished his remarks.

Does Pete Rose belong in the Hall of Fame? “If there is a Hall of Fame, Pete Rose has to be in it.”

Manny Ramirez being Manny! “He wanted a few days off late in the season and came by the office to let me know his hamstring was acting up.” Which leg? “Pick one,” Manny replied.

I attended with my buds, Dr. Joe Whitehead who played for Tech in 1955-56, and Dr. Tom DeBlack, Arkansas Tech’s official historian, if there is such a thing. It was a great evening, and no one seemed to be checking the football score on their phone.

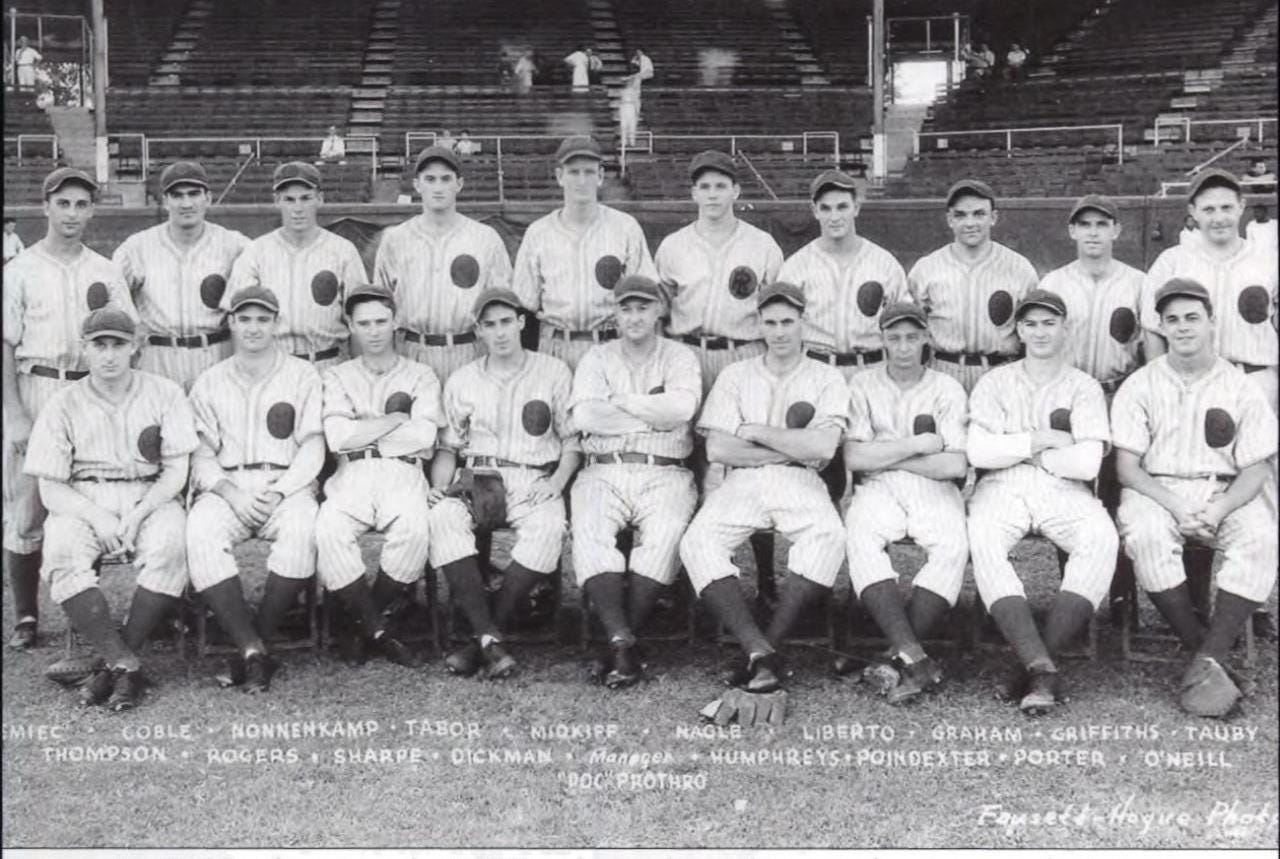

The Miracle of 1937

The Little Rock Travelers’ pennant-winning 1937 season is one of the most improbable stories in Arkansas baseball history. In a decade when finishing in the first division seemed unlikely, the 1937 Travelers won a title, swept the Yankees and Indians, and gave the city two of its favorite adopted sons. Please use the link below to read this amazing lost story.

That lost story is the feature story this week in Only in Arkansas. LINK

After reading the story of the 1937 Travelers come back and read about their shrewd manager.

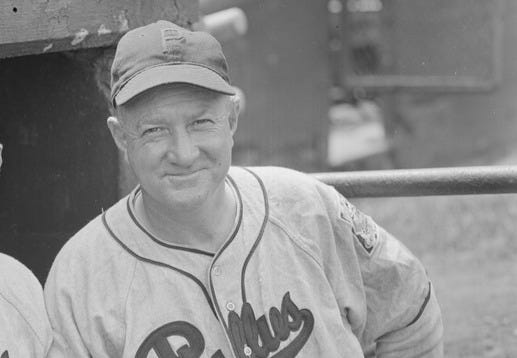

Doc

In the summer of 1920, James Thompson Prothro was practicing dentistry in Dyersburg, Tennessee, and playing second base for the town team when a persistent scout convinced him that he was good enough to be a major league infielder. Washington Senators’ scout Joe Engel was so adamant that Prothro was a pro prospect that he persuaded the Senators to put the dentist on a train directly to the big-league team that was wrapping up the season at Boston’s Fenway Park.

The scout was correct. On September 26, Prothro pinch-hit for the pitcher in the ninth inning, singled and knocked in a run. In doing so, Prothro became one of those fortunate footnotes in baseball history, a player who got a hit and an RBI in their first major league at-bat. Perhaps he was the first practicing dentist to do so.

The next day he started at shortstop and collected two more hits and another RBI. The rookie, whose teammates called “Doc” appeared in six games in his week with the Senators. He batted 13 times, finishing his short trial with a .385 batting average.

Prothro’s deal with the Senators included the option to decline and return home if he did not agree to a minor league assignment. In a decision that seems incomprehensible today, in 1921, when Prothro was assigned to the Senators farm club in Reading, Pennsylvania, he opted to return to his dental practice.

Prothro remained Dyersburg, Tennessee’s dentist until Washington re-signed him in the spring of 1923. According to Bill Nowlin, who authored Prothro’s story in the SABR Bio Project, some sort of mysterious agreement in Prothro’s Washington deal allowed him to play with the Memphis Chicks, just down the road from Dyersburg. He played 111 games with the 1923 Chicks and six games in a September call-up for the Senators. In the process, he found a baseball home in Memphis and became one of the city’s all-time favorite players.

From 1924 through 1927, Doc played in 168 major league games with Washington, Boston, and Cincinnati. Although he only played one full season, his cumulative batting average was .318. During those four years, he played 378 minor league games, 76 games with the Chicks in 1924, and 302 games with Portland in the prestigious Pacific Coast League.

Prothro also found some hidden power in the PCL. After 600 major league at-bats without a home run, he hit 24 homers in two seasons in Portland. Although the salaries and prestige in the PCL rivaled the big leagues, Doc Prothro negotiated himself back to Memphis as player-manager in 1928. His son, Tommy, was eight years old, and Doc Prothro was coming home.

Doc Prothro brought a pre-packaged baseball saga to Memphis. Fans and sportswriters loved the backstory of a dentist-turned-major-league-ballplayer. He had been a .300+ hitter in the big leagues, and, after moving out west, he had taken the Pacific Coast League by storm. In Memphis, he would be both a player and a manager and excel at both jobs. Best of all, he was their guy, from just up the road in Dyersburg.

Over the next seven years, Prothro’s Chicks won two pennants. His teams finished second and third twice, winning 637 and losing 438. He played 584 games in his player role, posting a cumulative .304 batting mark. To say Doc Prothro was a hometown hero would be an understatement, so when he left for Little Rock after the 1934 season, his departure was a mournful time in Chicks’ history. That year, their manager, the legendary baseball player James Thompson “Doc” Prothro left the ball club after seven glorious seasons at the helm.

After repeating his Memphis managerial heroics in Little Rock, Prothro earned the expected major league offer. In 1939, he accepted the challenge to manage the Philadelphia Phillies, one of the big leagues’ most beleaguered franchises. The Phillies had finished last in the National League in 1936, moved up to seventh in 1937, and returned to the cellar in 1938. So hapless were the Phils, that they finished 24 games behind the seventh-place team.

While Prothro had proven himself to be an exceptional manager at Memphis and Little Rock, he was not a magician. He led Philadelphia to three more consecutive last-place finishes and found himself back in Memphis managing the Chickasaws in 1942. The immensely successful minor-league manager’s record as a major-league field boss remains among the worst in baseball history (138–320).

In his second tour of duty in Memphis, Prothro guided the Chickasaws to two second-place finishes in six seasons, but he never regained the success of his first stint with the club. This time around he also had the difficult balancing act required by his position as part owner of the Chicks. In December 1947, the Memphis Commercial Appeal announced that Prothro had sold his share in the franchise to the Chicago White Sox and retired to his home in Arkansas.

Thompson Prothro and his wife, Katherine (the only known person who preferred “Thompson” over ‘Doc”), followed the lead of his old friend Harry Kelley and bought a 616-acre farm about 30 miles down the road from Kelley’s operation in Wynne.

The Arkansas farm was a new adventure for the dentist-turned-baseball-man. The retirement estate was handy to a train stop the railroad company called “Prothro.” Doc and Katherine needed the train access to follow their son, Tommy, who had embarked on a coaching career that would lead the younger Thompson Prothro to induction into several halls of fame.

One of those hall of fame selections was the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame where James Thompson “Doc” Prothro, the baseball man (1973), and football coach James Thompson “Tommy” Prothro Jr. (1988) share a common honor.

______________________________

Link to Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. Save it somewhere if you do not feel comfortable subscribing. Look for a new post on Monday evening.

Currently, there are about 300 subscribers in our community. The biggest benefit for me is that I can email any subscriber personally to discuss our shared love for baseball history.

Please consider a free subscription to Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly. These posts will always be Free.

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/