Backroads and Ballplayers #87

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Another Moon Story, the Lost Story of “Klondike Kane,” and personal thoughts on 2024.

Another Moon Story

A Good Day in the Swamp - Story by Subscriber Herb Lunday, Contributed by Subscriber Bob Sivils…

My buddies and I were having a good day on Bird Lake, deep in the cypress swamps of the Cache River in eastern Arkansas. I’ve forgotten who was there that day. It was usually Arthur Bowie, Quinton Hollingsworth, Sonny Thompson, and James Brown. Mallards were flying low, cupping straight into the blind over the decoys (and surely in response to the sweet sounds of our calling).

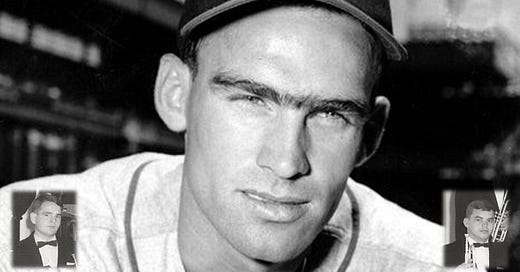

After we had fired several volleys that morning, we heard an outboard motor leaving the river and coming down the narrow, log-filled slough to our blind. We listened to the familiar sounds of water lapping against aluminum as they stopped the motor and coasted underneath the blind to conceal the boat. A couple of guys got out. We knew one of them. It was Lloyd Henry, an attorney who once lived in our hometown but had moved over to Searcy. He introduced the other fella. The name didn’t register, but he looked like a square-jawed athlete chiseled out of a block of granite. “Not much action over at Dupree,” Lloyd said, knowing he was welcome in our blind, “but we heard you shooting all morning.” We all settled back in and enticed a few more bunches. As we were picking up mallards, we noticed a beautiful drake was banded. “My friend got that one,” Lloyd announced. Well, how did he make that calculation with all those 12-gauges blasting in rapid-fire mode? But, he was older and we respected his keen eye. We motored out single file in several boats and then walked a mile through wooded backwater to our trucks. Much of the way out I watched that banded mallard bouncing along the leg of Lloyd’s friend. “That oughta be mine,” I continued thinking to myself. I was sure of it. We parted cordially after our good hunt, never to see Lloyd or his friend again. The friend? Some guy named Wally Moon.

______________________________________________

This extraordinary personal encounter was shared by my old friend Bob Sivils, who credits the story to his college buddy, new subscriber Herb Lunday.

Bob is a retired educator who taught music and directed bands in several Arkansas and Oklahoma high schools. His unique sense of humor and devotion to his students are legendary among his friends and colleagues.

According to Sivils, Dr. Herb Lunday, a friend of Sivils from their college days at Arkansas Tech, was among the most talented trumpet players in Arkansas Tech’s history of exceptional musicians.

Dr. Lunday is retired from a career in higher education. He spent the last 21 years of his career as Dean of Student Services at Missouri State University-West Plains. Lunday remains a baseball fan somewhat afflicted with an incurable addiction to nostalgic stories from the colorful history of Arkansas/Missouri baseball. I love this “Duck Hunting” story. Thanks for sharing.

The First Arkansas-born big Leaguer of the 20th Century

Lost Story - “Klondike”

I have written often about the “characters” of Arkansas baseball history. Some were uneducated hillbillies, some were college guys, and a few were the somewhat privileged sons of country doctors. The first Arkansas-born major leaguer of the 20th century fit none of these typical big-league profiles. He was the son of Jewish merchants from St. Louis and he was probably born in Arkansas by accident. Although our state’s first 20th-century big leaguer did not share most of his contemporary’s ancestry or culture, he epitomized the entertaining uniqueness Arkansans brought to the game.

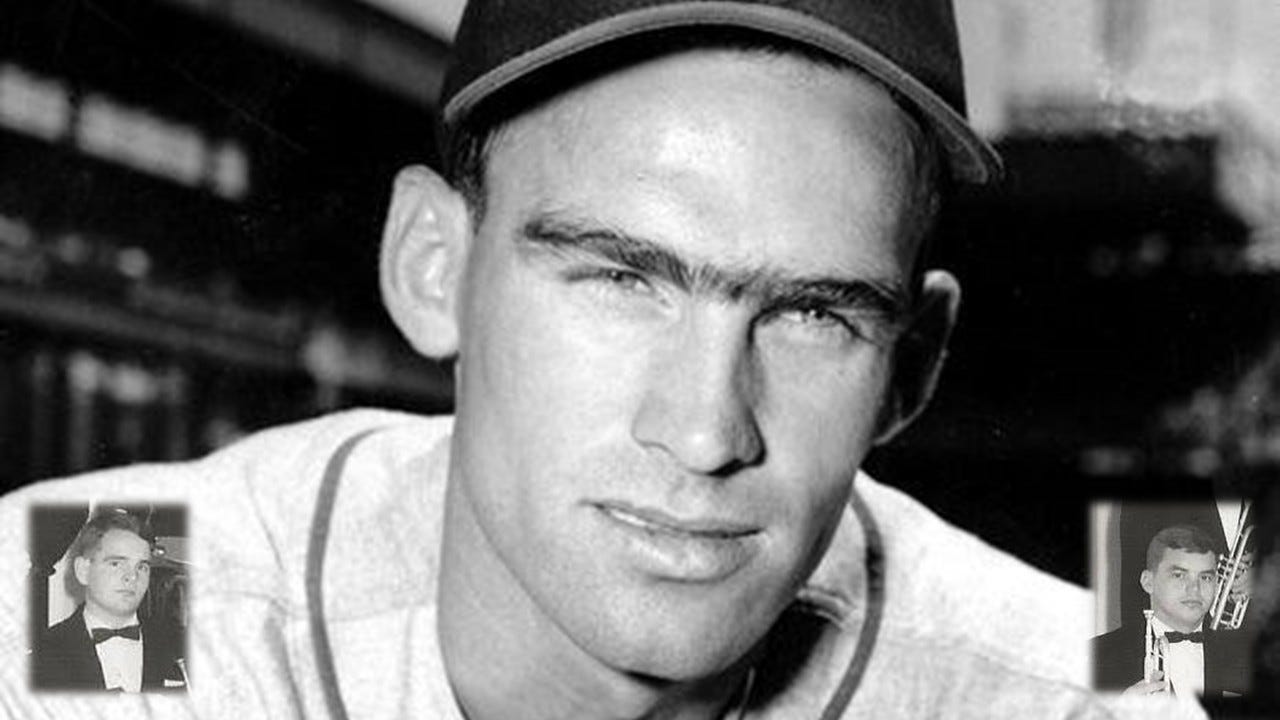

The baseball player known in the early 1900s as Harry Kane was born Harry Cohen in Hamburg, Arkansas sometime in the mid-1870s. Although his date of birth is questionable, and his baseball name was fictitious, the fascinating story of Harry Kane is very real. If 1900 is accepted as the beginning of what is now known as the “modern era” of major league baseball (fervently debated), Kane was the first major leaguer born in Arkansas.

Why the assumed name? Cohen’s South Arkansas family was Jewish, and many young Jewish ballplayers of that period changed their names to avoid controversy. “It’s impossible to know the precise number of Jewish players of that era since not a few of them operated incognito for fear of anti-Semitism.” - Ford Frick, former Commissioner of Baseball

It seems likely, that while assuming a new name would improve his chances in professional baseball, a new birthday would also benefit his career. Like many aspiring ball players of his era, Kane obviously decided being a few years younger would also be advantageous.

In March of 1900, Arkansas-born Harry Kane signed a professional baseball contract with the Denver Grizzlies. He had earned a reputation as a pitcher back home in St. Louis, where he clerked in the family dry goods store and played semi-pro baseball in the competitive leagues around the city.

Pro baseball men had been keeping an eye on Kane in St. Louis, and he came to Denver with great promise, tempered by concern about his lack of experience. “Not a pitcher in the National League has more speed, but he lacks control, and he has no knack for using his head.” Hausen (catcher) will break this man in no time.”

Harry Kane the pitcher seemed to be a pro prospect, but Kane the impetuous young man was unpredictable. He picked up his first professional victory late in the summer of 1900, but he left the team in September before the season ended. According to newspaper accounts, Kane had been offered a position with a dry goods store in St. Louis that he could not turn down.

From that abbreviated debut season, Kane would spend more than 30 years in baseball as a player, manager, and later an umpire. Diamonds in the Dusk described Kane’s tumultuous baseball life as a “quasi-vagabond” existence. The much-traveled Kane changed uniforms “at least” 34 times.

Back in St. Louis, Kane rejoined the St. Louis semi-pro circuit in the summer of 1901, but by the spring of 1902, he was back in the minor leagues. In March, local papers announced the 23-year-old Kane had signed with the San Francisco Seraphs of the California League. “Kane is a southpaw and bears an excellent reputation here.” St. Louis Republic

Harry Kane began his remarkable 1902 season with the Seraphs where he was matched twice against the great Rube Waddell. The unrestrained Waddell was pitching in Los Angeles while on one of his regular escapes from disputes with A’s manager, Connie Mack. Kane and Waddell split the victories.

By late June, Waddell and Mack had reconciled and Rube was back in Philadelphia. Kane had become dissatisfied in California and he had also found a new home in Springfield, Missouri. With the Springfield Midgets, Kane became a dominant pitcher and something of a folk hero.

If young Cohen selected “Harry Kane” as his new baseball identity to produce some notoriety, he may have been disappointed that fans did not get the relationship of Harry Kane to “hurricane.” Just in case, Kane decided to add “Klondike” to his name. In reality, he did not need the new nickname to get attention.

Klondike Kane won ten consecutive games in Springfield and was the center of adulation without a colorful moniker. Addressing local fans’ concern about his restless nature, Kane announced he was in Springfield to stay, but revealed to the press that he didn’t sign contracts in order to keep his options open.

On August 1, Kane predictably decided he was ready for the major leagues and headed to St. Louis to avail himself to the Cardinals. The Cards weren’t interested, but the cross-town Browns would take a chance. By August 8, 1902, he was in uniform with the Browns and pitched three innings of scoreless relief.

Unfortunately, the successful debut was not an indicator of Kane’s readiness for the major leagues. He was hit hard and often in successive appearances, including a 15-hit assault by the A’s on August 21st. During his three weeks in St. Louis, Kane was 1-4 with a 5.48 ERA. The Browns dropped from 3rd to 4th in the standings during that period, and the press blamed Kane.

By late August, a restless Kane had contacted the Midgets and asked to return. Since Springfield needed pitching and Kane was popular with the fans, his transgressions were quickly forgiven. He had deserted Springfield to give the majors a shot but he was welcomed back as if nothing had happened.

Statistics for Kane’s split year in Springfield are sketchy, but local newspapers credit him with 20 wins and only 1 loss for the two stints with the Midgets. If news accounts are accurate, Kane’s combined record with San Francisco, St. Louis, and Springfield was 26-11.

Klondike Kane, the toast of Springfield, was back with the Midgets in 1903, where he won 22 and lost 12, before a late-season call back to the majors with the Detroit Tigers. Once again Kane was ineffective in the big leagues. He pitched 18 innings and gave up 26 hits, with no wins, two losses, and an 8.50 ERA.

Kane split time between five minor league teams in 1904 and 1905, winning 20 games in ‘04 and 22 in ‘05. Once again, he earned a major league chance with the Philadelphia Phillies in late September of 1905. On September 27, Kane pitched a 6-0 shutout over the Cardinals, it was Harry Kane’s finest hour.

His 1.59 ERA in 17 innings late in 1905 earned him a spot on the Phillies’ 1906 Opening Day roster. He remained with Philadelphia until May 15th when he failed to last the first inning of a start against Brooklyn. It would be his last major league appearance. Baseballreference.com lists his age at the time as 22. He was likely in his 30s.

Over the next ten years, Harry Kane, the baseball nomad, would play and manage in towns from the Georgia coast to the Montana Rockies. After his playing career ended, he became an umpire, first in Texas and finally earning a promotion to the Pacific Coast League, just one step below the majors.

Harry “Klondike” Kane lived his entire life with his bags packed and his options open. Kane experienced American baseball from the relative luxury of the major leagues to the converted cow pastures of back roads semi-pro circuits. He knew nothing else. Kane opened modern baseball’s “Dead Ball Era” in 1900 and saw the game forever changed by the glamour of the home run in the 1920s.

“Klondike” Kane was the first Arkansas country boy in major league baseball but was soon followed by other rural Arkansans. Unsophisticated young men with colorful nicknames like Boss, Rube, Mutt, and Rabbit caught the imagination of baseball fans and sportswriters alike.

On September 13th, 1932, Harry Klondike Kane (Harry Cohen) collapsed during an umpiring assignment in Portland, Oregon. He died two days later.

Personal thoughts on 2024:

Sharing my induction to the Arkansas Tech Hall of Fame with family, coaches, and former players was one of the highlights of my life. These young women began their careers playing before a sparse crowd of mostly parents and friends. A few years later they played a National Tournament game before more than 2,500 fans in Tucker Coliseum.

They called my name at the induction ceremony, but the honor belongs to my staff, our loyal fans, and the amazing players who changed women’s college basketball forever

Early last summer a young PBS producer named Shotaro Kanari called to ask for my help in creating a documentary on Hugo Bezdek to air at halftime of the Arkansas High School football playoffs on PBS TV. I had no idea how that would go. It turned out to be far beyond all of my expectations. I am very proud of the final product. All the credit for the “Father of the Razorbacks” belongs to Kanari and the amazing staff at Arkansas PBS.

Hugo Bezdek, Father of the Razorbacks Produced by Arkansas PBS, 2024

I was asked last week to list my favorite story from 2024 among my contributions to Only in Arkansas. First Security Bank sponsors Only in Arkansas. The outstanding online magazine is edited by the amazing Stephanie Buckley of Petit Jean Coffeehouse fame. I am humbled to be part of such an outstanding publication. Like the Natural State OIA promotes, there is something for everyone at Only in Arkansas.

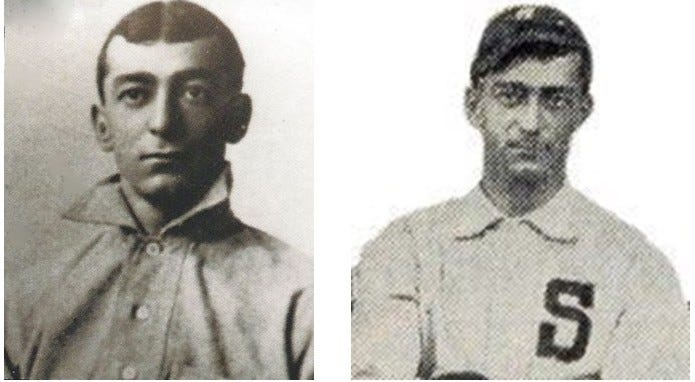

My favorite contribution for 2024 was the story of a barnstorming team of African American major leaguers who made a stop in Little Rock on October 10, 1955. The story also includes an inconceivable encounter with an amazing gentleman who was there that evening 70 years ago. A Forgotten Night in October, 10-21, 2024, Only In Arkansas.

_______________________________

Here is a link to Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. Save it somewhere if you do not feel comfortable subscribing. Look for a new post on Monday evening.

I also understand that you can turn on notifications for my page which will send you an alert whenever you post something new.

To turn on notifications for a favorite Facebook page, go to the page itself, and click "Following.” Under "Notifications" select the type of posts for which you want to be notified. Choose Standard" or Highlights. This will prompt Facebook to send you alerts whenever the page posts new content. Maybe!

Currently, there are about 300 subscribers in our community. The biggest benefit for me is that I can email any subscriber personally to discuss our shared love for baseball history.

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Jim, what a year it has been for you. I am so honored to call you friend. I know Mike would be the first to shake your hand in congratulations, then give you a big hug! May 2025 hold as many exciting endeavors for you. Happy New Year! I am waiting for pitchers and catchers to report!