Merry Christmas, Important Announcement, Rickey, and back to 1940s Nicknames

I am humbled (and honored) to have about 500 readers of these weekly posts. My mission is to save the stories of Arkansas baseball history. Thanks for joining me on this adventure. Your readership is a wonderful gift and your friendship is a blessing.

Important Announcement:

ALWAYS FREE will never change!

Some of my readers distrust subscriptions, and I have tried to provide an alternative to a subscription by posting a link to each weekly blog/column on my Facebook page.

I have discovered that my “followers” do not necessarily get a notification that I have posted a new Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly, therefore I have paid Facebook each week to “Boost” my post.

I will continue to link each weekly blog/column to my Facebook page after every post, (usually Monday evening), but I am asking you to help me discontinue buying Facebook “boosts.”

Here is a link to Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. Save it somewhere if you do not feel comfortable subscribing. Look for a new post on Monday evening.

I also understand that you can turn on notifications for my page which will send you an alert whenever you post something new.

To turn on notifications for a favorite Facebook page, go to the page itself, and click "Following.” Under "Notifications" select the type of posts for which you want to be notified. Choose Standard" or Highlights. This will prompt Facebook to send you alerts whenever the page posts new content. Maybe!

That said, please subscribe if you wish, and share if you can. Currently, there are about 300 subscribers in our community. The biggest benefit for me is that I can email any subscriber personally to discuss our shared love for baseball history.

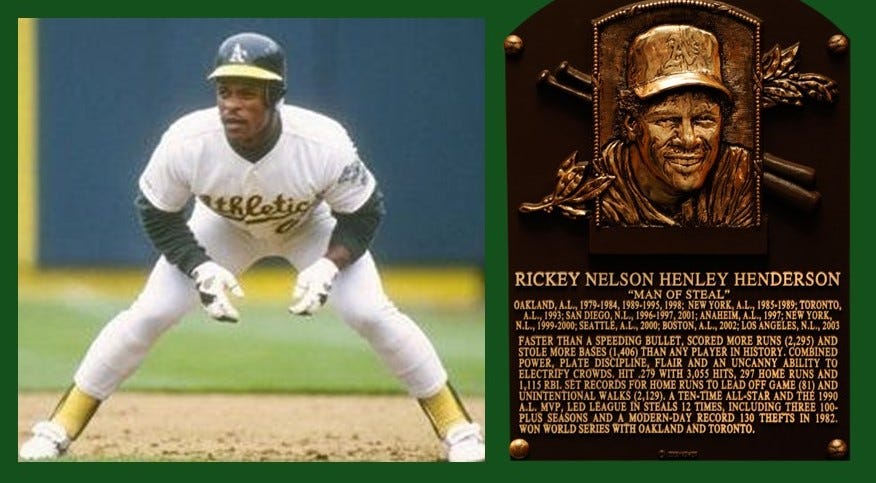

Rickey,

Rickey Nelson Henley Henderson was born in the back of a car on Christmas day, 1958.

He loved to play baseball. Rickey might have played for free, in fact, he almost did when he joined the Newark Bears in the independent Atlantic League at age 45. By the way, he stole 37 bases during his time in Newark, and he was thrown out twice by catchers who probably tell that story once a day.

Rickey was certainly fun to watch, even if he was on the opposing team. He has almost as many famous quotes as Yogi. Most of his memorable quotes are in third person.

The voicemail left for the Padres GM late in his career is my favorite and sums up his love of the game in a few words, “Kevin, this is Rickey, calling on behalf of Rickey. Rickey wants to play baseball.”

“Rickey played a cautious sport with abandon. Rickey played a timid sport with flash. Rickey irritated and thrilled and frustrated and dominated and left us all wanting more.” —Joe Posnanski

Do you have a Rickey story?

_____________________________________________

1940s More Nicknames: “Hooks” and “Jittery Joe”

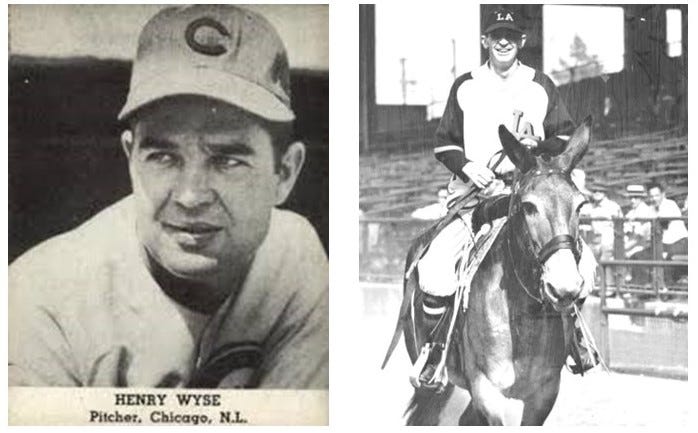

Henry “Hank” “Hooks” Wyse

Twenty victories in a single season is considered a benchmark for success as a pitcher. Moving that arbitrary mark to 22 wins suggests an even more selective accomplishment and creates an unofficial elite fraternity of Arkansas’ distinguished major league greats.

The list of Arkansas-born major league pitchers who reached 22 or more pitching wins in a season reads like an honor roll of celebrated stars. The “22-win club” includes Dizzy Dean, who accomplished the feat three times, Lon Warneke, who won exactly 22 on two occasions, and Cliff Lee, who won 22 in his Cy Young Award year of 2008. The other well-known names in the prestigious group are Ellis Kinder, Johnny Sain, Preacher Roe, and the not-so-famous “Hooks” Wyse.

All the prominent pitchers on our list, except Wyse, have been chosen for the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. The list includes Cy Young Award recipients, World Series heroes, Baseball Hall of Fame members, and the considerably less renowned, “Hooks” Wyse.

Henry Washington Wyse was born in Lunsford, Arkansas, in 1918, or perhaps a few years earlier, if the 1920 census is accurate. The census indicates Henry was 4 and 11/12 years old in 1920. It would be common among pro baseball players in Wyse’s era to “lose” a few years to be more attractive prospects.

Regardless of his age, Wyse was raised in hard times. Assuming his accepted birth date, Wyse lost his father at age 12 and dropped out of school in eighth grade to help his family get by during the depression. By his mid-teens, he was working full-time for a lumber company in Trumann and playing semi-pro baseball for the company team on weekends.

His big break came in the summer of 1940 when he was spotted by the Chicago Cubs pitching in the Kansas Ban Johnson League. Although the United States was not officially involved in World War II, many professional players had joined the military, and pitchers were in short supply. By the end of his first summer in the minor leagues, Wyse had been promoted to the Cubs AA farm team in Tulsa.

Back in Tulsa for the 1941 campaign, Wyse had an attention-getting season. He won 20, lost only four, and posted a team-leading 2.09 ERA. Wyse’s performance led the Oilers to the finals of the Texas League playoffs, where he was outstanding in a losing effort.

In 1942, Wyse was again impressive for the Oilers. He and fellow Arkansan, Jittery Joe Berry, pitched in 88 games and combined for 38 pitching victories. The remaining members of the Tulsa staff won 36.

Wyse’s 20 wins led the Oilers, despite an early September promotion to the Cubs. He was 2-1, in 28 major-league innings, including a complete-game shutout of the Phillies on September 17th.

Wyse had an exemption from his draft board back in Arkansas, due to the care required for his seriously ill wife. He missed 1943 spring training to be with his wife, but the Cubs saved a spot on their roster for his return. Wyse had earned his permanent major league promotion, and despite a late start, he became an integral part of the Cubs pitching staff. After his return in May, Wyse started 15 games and relieved in 23. He picked up nine wins and five saves.

Wyse returned to the Tulsa area in the winter of 1943. He and his young wife had made their off-season home in Oklahoma since his days with the Oilers. Hank worked in a defense plant and continued to deal with his wife’s declining health. Rowena Patrick Wyse died on November 21, 1943. She was 24 years old.

The 1944 Cubs finished fourth, their first appearance in the first division of the National League since 1939. Wyse led the team in wins, games started, and innings pitched. The master of a knee-buckling curveball, Wyse was tagged with the nickname “Hooks” by his teammates. In a harbinger of things to come, the 1944 Cubs went 24-16 in their last 40 games.

Cubs fans were accustomed to disappointment, but the 1945 season would be magically different. As the season began, some regular players were being discharged and returning to their major league teams, but rosters were by no means at pre-war levels. Overall talent was still more equivalent to the high minors than the big-league level. Chicago was better off than many clubs, with a starting eight similar to the two previous seasons and their ace pitcher, Hooks Wyse, still not called by his draft board.

In mid-June, the Cubs were in the middle of the standings, and Wyse was a respectable 7-5 when bad news arrived. No longer the caretaker of an invalid wife, Wyse was summoned by his draft board in Oklahoma to report for induction on June 24th.

Although Wyse had previously passed a military physical in 1944, he had suffered a work-related injury to this back in the winter of 1945, and he now wore a medical corset when he pitched. The new injury was debilitating enough for Wyse to be permanently rejected for military service before induction.

On July 1, when Wyse joined the club in New York, the Cubs were in 4th place, five games behind the Dodgers. After a 36-hour train ride from Oklahoma, Wyse pitched the second game of a doubleheader and beat the Giants 4-3. That remarkable win, by a pitcher who had been idle for ten days, began one of the most remarkable months in Cubs history.

The Cubs’ win on Wyse’s first day back in uniform, began an 11-game winning streak and a 26-6 record for July. Wyse was the winning pitcher in eight of those victories. In one month, the Cubs went from 4th place to league leaders, five games ahead of the Cardinals and Dodgers. Wyse’s return was the catalyst for the Cubs’ historic ascent.

The Cubs didn’t maintain their torrid mid-summer pace, but they held off the Cardinals and Dodgers the rest of the way and finished in first place by a game and a half over the second-place Cards. Hooks Wyse won 22 games, second in the National League. He was also second in the league in innings pitched and third in winning percentage. Wyse was named to the Associated Press National League All-Star team, although the official All-Star Game was canceled because of the war-time travel restrictions.

Wyse did not have a very good World Series. He was the losing pitcher in Game Two and gave up three runs in less than an inning’s work in Game Six. Despite the lackluster performances in two appearances, Wyse thought he was the obvious choice to start Game Seven. He had been the anchor of the pitching staff throughout the season, but manager Charlie Grimm chose Hank Borowy who had pitched the last four innings of the Cubs victory in Game Six.

Borowy gave up four runs in the first inning and failed to record an out. The Cubs never recovered, and the Tigers wrapped up the World Series in a 9-3 rout. In an interview in 1998, Wyse still felt the manager’s decision cost the Cubs the World Series. “It was Grimm’s fault,” Wyse stated bluntly. “It was a mistake. I thought so then and I still do.”

Wyse remained with the Cubs for two seasons after the “regulars” returned from military service. He was the ace of the Cubs’ staff in 1946, and his 14 wins led the team. His excellent 2.68 ERA, against the full rosters replenished after the war, was 7th best in the league and matched his mark for the previous year. The Cubs finished third, a distant 14 ½ games back. In 1947, Wyse dropped off to 6-9 with an ERA of 4.31. He was demoted to a long reliever by mid-season and the Cubs faded to sixth place.

Bone spurs in his elbow sidelined Wyse in 1948 and the Cubs optioned him to Shreveport in the Texas League. Wyse recovered well enough to get a last major league chance in 1950 with Connie Mack’s Phillies. It was Mack’s last year to manage, and Wyse’s last year as a pitcher in a big-league starting rotation.

At age 33, or perhaps several years older, Hooks’ dominating curve was no longer big-league quality. Washington purchased his contract from Philadelphia in May of 1951, and the Senators subsequently sold him to the Yankees a month later. Farmed out to the Yankees’ minor league club in Kansas City for the remainder of 1951, Wyse was finished as a major league pitcher.

Determined to continue pitching, Wyse pitched two more somewhat successful minor league seasons before retiring in 1953. He finished his career with very respectable major league totals that included 79 wins and a 3.52 career ERA. His minor league record of 115-69 and a 3.15 ERA are even more impressive.

Perhaps you have never heard of Hooks Wyse. His 194 professional wins rank 10th among native Arkansans.

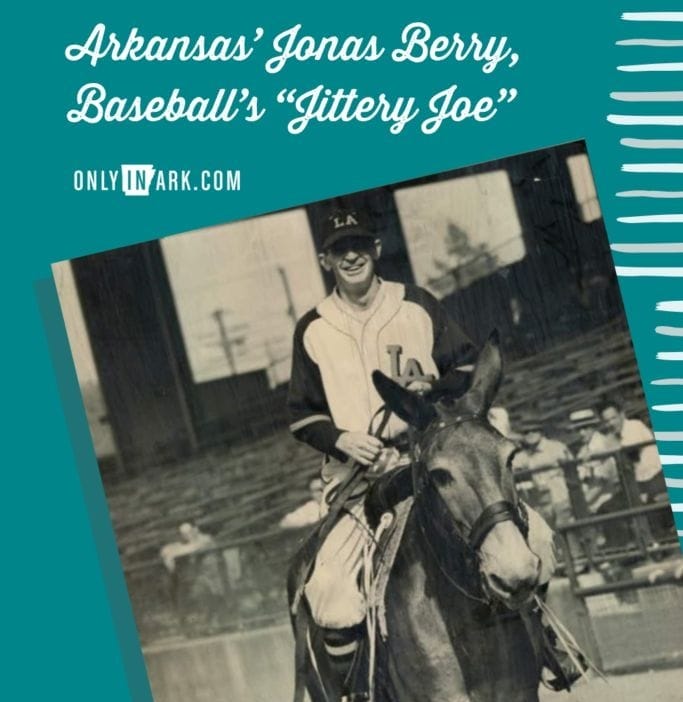

“Jittery Joe”

The story of Jonas Arthur Berry is among my favorite “lost stories” in Arkansas baseball history. He was a teammate of Hooks Wyse in Tulsa.

They called him Jittery Joe, and he made his first big-league appearance on September 6, 1942. Behind 3-0 and going nowhere in the standings, perhaps Cubs’ manager, Jimmie Wilson, was more curious than hopeful about this strange-looking fellow in his bullpen.

His appearance did not exactly strike fear in opposing hitters. The rookie pitcher was maybe 5’ 9” and on a good day weighed about 135 lbs. His uniform hung from a wiry frame like a child in an adult’s shirt, and his county stride walking to the mound was almost comical. Jittery Joe had been dominating for Tulsa in the Texas League in the 1942 season, but it took considerable imagination and some apathy for a major league team to give him a shot. Incidentally, Jittery Joe was 37 years old, and he had pitched more than 3,000 innings over 16 seasons to earn this chance.

Click here for the complete story of Jittery Joe Berry.

Book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

My favorite Rickey story is that Harold Reynolds led the AL in steals in 1987 with 60, in a year Rickey was injured. Sometime in the offseason, Reynolds' phone rings and he picks up. Henderson simply says, "Rickey would have had 60 at the break" and hangs up.

Merry Christmas, Jim!

Rickey lived with his grandmother in Pine Bluff AR from age 2 to 7.