Backroads and Ballplayers #84

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

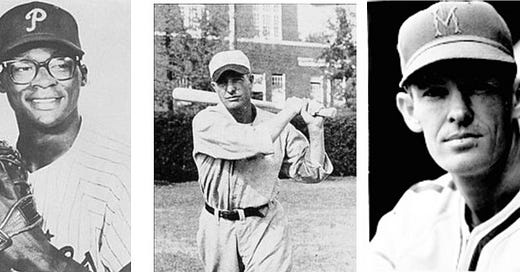

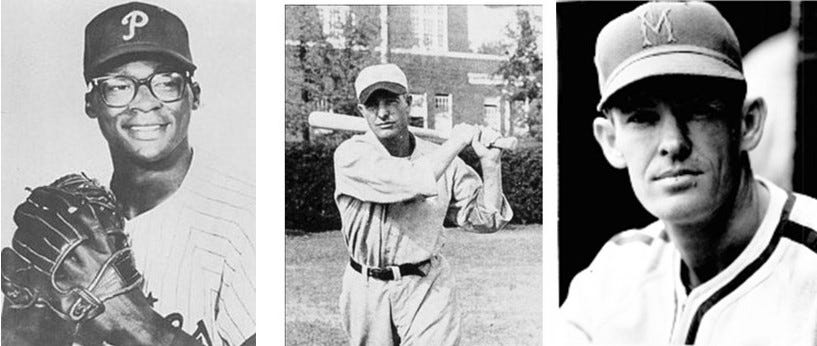

Dick Allen 1963, The Lost Story of a Three-Time All-American, and Nicknames

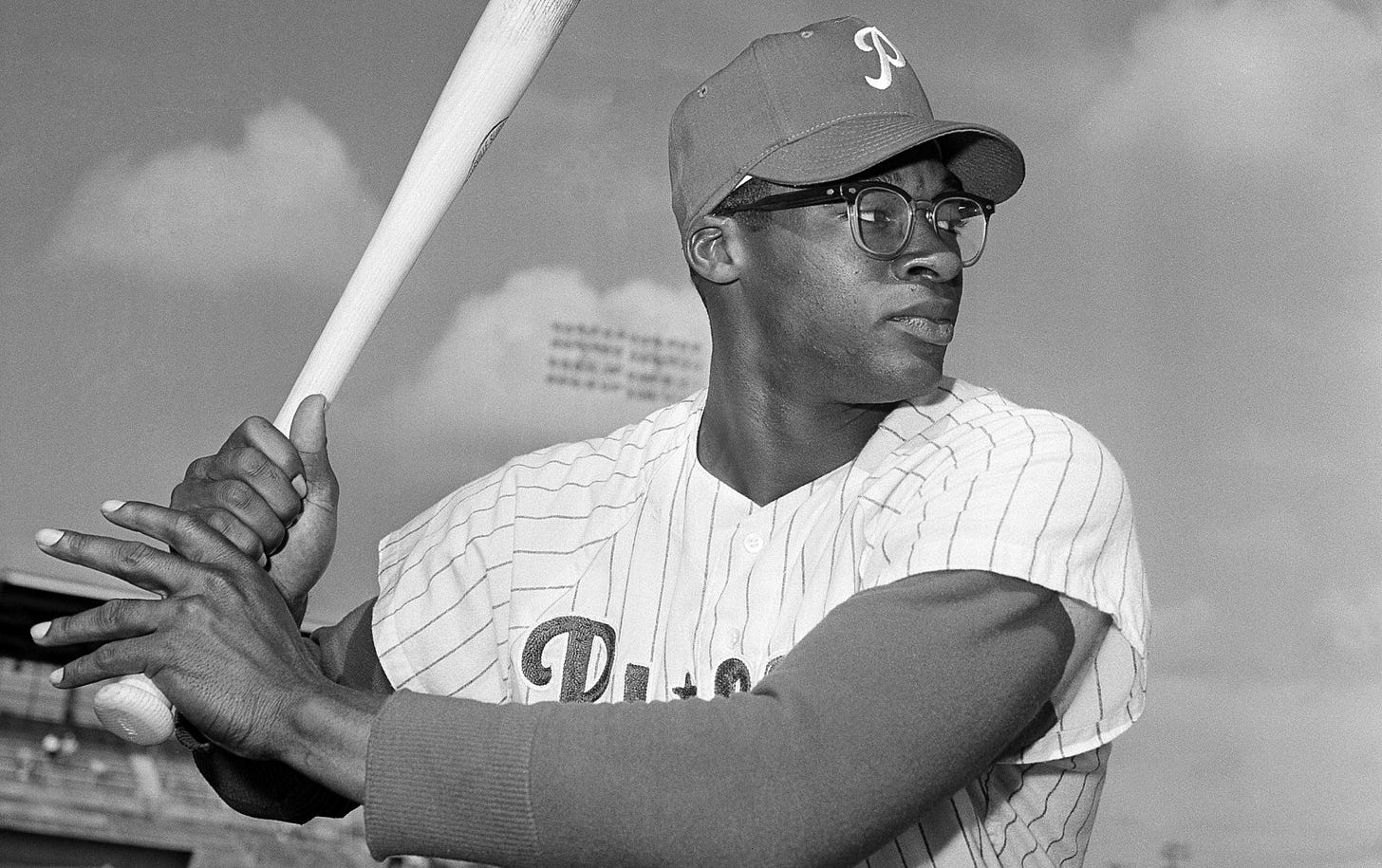

Dick Allen in Little Rock

A few years ago my beloved cousin, editor, and sister substitute gave me a treasure called The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. It is a hardback of some substance, published in 1993 by Baseball America. Although my “Official Record Of Minor League Baseball” is more than 30 years out of date, it is always on my desk.

According to THE ENCYCLOPEDIA, the 1963 Little Rock Travelers competed in the South Division of the International League, minor league baseball’s highest level. The ‘63 Travelers finished third in the South and seventh in the 10-team league in attendance. It took complicated circumstances for the Travs to be members of the International League South with Indianapolis, Columbus, Jacksonville, and Atlanta. The 1963 season would be Little Rock’s only year in the International League, but that is another story.

The Minor League Encyclopedia has only facts, records, and league leaders. In 1963, a guy the encyclopedia calls Richie Allen of the Little Rock Travelers led the league in home runs (33) and RBIs (97). Last week the Classic Era Committee selected Richard Anthony Allen as a 2025 inductee into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

I would love to write that 1963 went well for the first African American to play for the Little Rock Travelers. On the field, things were great. He led the team in hits, runs scored, home runs, triples, and RBIs. Outside the ballpark, Little Rock was still a segregation stronghold, and Allen later described a personal discomfort that often became fear.

On Opening Night, Governor Orval Faubus threw the ceremonial first pitch before a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 7,000, some of whom carried hand-lettered signs opposing a Black player on the Travelers. According to Bob Razer’s excellent entry in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, out in left field, the Travelers’ first African American repeated the twenty-third Psalm to himself.

As baseball writers are fond of saying, “The baseball found” the petrified Allen on the first pitch. A routine fly ball to left field went over his head and rolled to the wall. Allen recalled, “I froze. I missed the ball because I was scared. I don’t mind saying it.” He later hit two doubles in the Opening Day game the Travs won 4-2. The Arkansas Democrat story was far different than Allen’s perception of his welcome.

“The fans gave Allen a hand as he stepped to the plate his first time, which showed that they were behind him 100%.” Arkansas Democrat April 1963

Loyal Reader Dennis Ritchie reminded me last week that there seems to be an inexplicable lack of details about Dick Allen’s year in Little Rock. It was an unusual time. Being moderate and tolerant was not popular politically or financially. The two state newspapers very carefully wrote only about Allen’s life on the field and avoided his struggles with the culture of his summer home. Both the Democrat and Gazette had lost advertisers and subscribers by condemning the absurd action taken when Governor Orval Faubus blocked nine children from attending Central High School because of their race.

Dick Allen was obviously hardened by his minor-league experience. He would later write that in Little Rock he learned that two sets of rules existed: one set for the white players and one set for Allen. In the future, if there were going to be two sets of rules, he would see to it that the rules governing him were of his own choosing.

He developed his own standards for personal behavior. He was a tough interview for the press, and on several occasions, Allen was branded as a distraction in the clubhouse. None of those offenses should have postponed his Hall of Fame induction to a time when he was not here to receive the honor in person.

Dick Allen spent most of his retirement life in Los Angeles, California. In December 2014, he missed being elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by only one vote. Richard Anthony Allen died on December 7, 2020. In 2025, he will finally be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

If you are a subscriber to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, be sure to read Philip Martin’s op-ed about Allen in last Sunday’s edition.

The Forgotten All-American

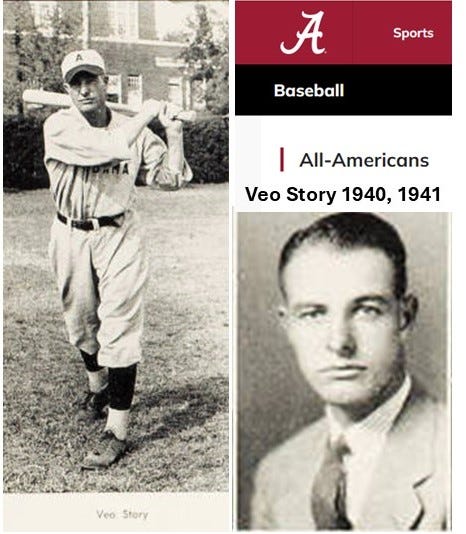

If there are degrees of “lost,” this biography of a country boy from the foothills of the Ozarks is one of the “most lost” in Arkansas baseball history. He starred at every level before and after World War II, yet his story has virtually disappeared.

He excelled in three sports at Arkansas Tech, made three All-American teams, played on two SEC Baseball Championship teams, and hit .299 as a professional baseball player. In his shining moment, he was chosen the Most Valuable Player in a prestigious national tournament. He is not a member of the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame nor the halls of fame at the colleges he attended.

His name is Veo Story and saving a story like his is the primary mission of Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly. Story was born on November 25, 1918, on a farm in the Northern Pope County community of Hector. In the first half of the 20th century, the rural hamlet was a tiny unincorporated village. Hector was named after President Grover Cleveland’s dog and the last stop before entering the back roads into the Ozark Mountains. There is no sign outside Hector welcoming travelers to the home of one of the area’s most successful baseball players.

Story enrolled at Arkansas Tech in the fall of 1936 and became an immediate starter in basketball and baseball. By 1939, he was the leading hitter on the baseball team, the leading scorer in basketball, and finished second in the pole vault in the state meet, won by Arkansas Tech.

After graduating from what was then a junior college, Story enrolled at the University of Alabama in the fall of 1939. Perhaps Alabama found Story, or Story found Alabama, on the advice of Arkansas Tech coach John Tucker, who had played for the Crimson Tide National Championship football team in 1930. The distance from a farm in Pope County, Arkansas, to the SEC cannot be measured in miles.

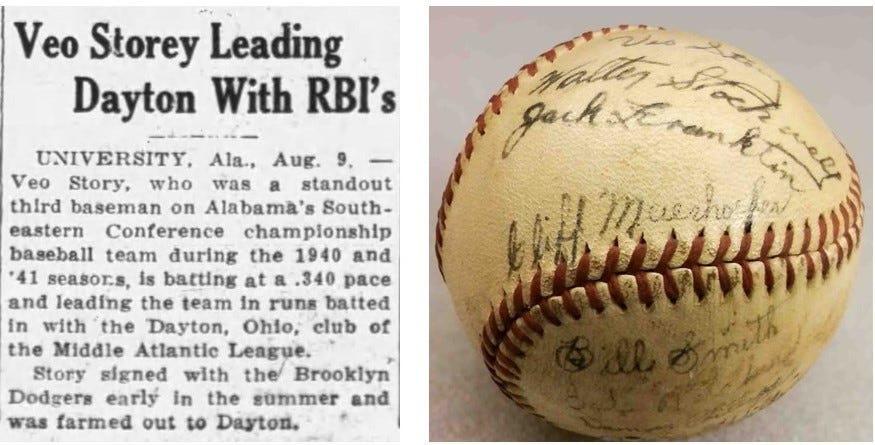

Despite a jump from the AIC to a nationally competitive program, stepping up to the Southeastern Conference was a smooth transition for Veo Story. His “long-range set shot” earned him a spot in the basketball starting lineup and he batted .340 in his two seasons of SEC baseball. In 1941, after leading the Tide to a second consecutive SEC baseball title, Veo Story was named an All-American for the second time.

After his last season at Alabama, Veo Story signed a pro contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers. That summer the Dodgers skipped the low minors and placed their new infield prospect directly to the Dayton Ducks, a Class C team with older more experienced minor leaguers. As he had done when he moved from a tiny rural high school to Arkansas Tech, and later from a small junior college to Alabama, Veo Story became an immediate success.

He batted .312 and led the team in runs scored, games played, and hits. Veo Story was 22 years old and among the younger players on the Ducks. He looked like he was on the fast track to the major leagues. That seemingly inevitable promotion never happened. It was the summer of 1941, and Veo Story’s life was about to take a detour.

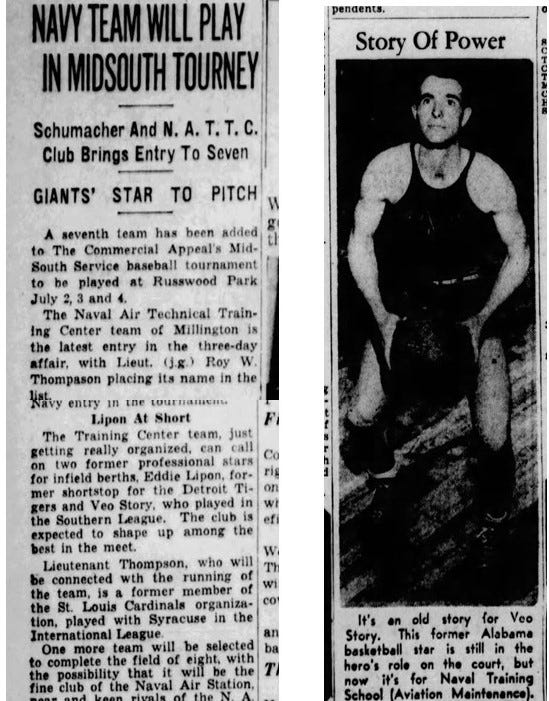

From 1941 until the summer of 1945, Story served his country in the Navy. While in the Navy, Story made headlines in various semi-pro basketball contests. He began as a “Chief Boatswain's Mate at Naval Training Station Norfolk in March of 1942, but appears to have graduated from the Tunney School and was redesignated an Athletic Specialist and transferred to the Memphis Naval Air Training School on 12/22/1942” —Chevrons and Diamonds link below

Information courtesy of Chevrons and Diamonds. (highly recommended)

When he resumed his pro career in 1946, minor league baseball had changed significantly. The professional players from the pre-war days were back, but teams were looking for young prospects. Veo Story was now 27 years old and among the oldest players on his Class B Asheville Tourists. He played in 135 games and batted .298, but at age 27 his time had run out as a big-league prospect. The Dodgers released him to a new Class B team at Reidsville, North Carolina, where he spent most of 1947, before a demotion to Class C the last month of the season.

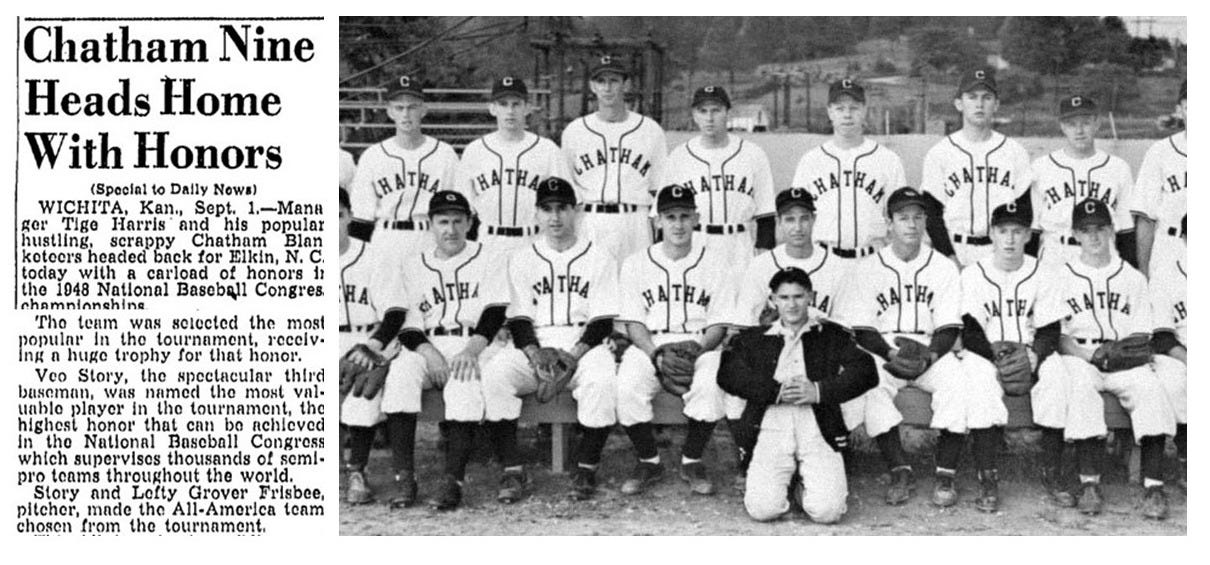

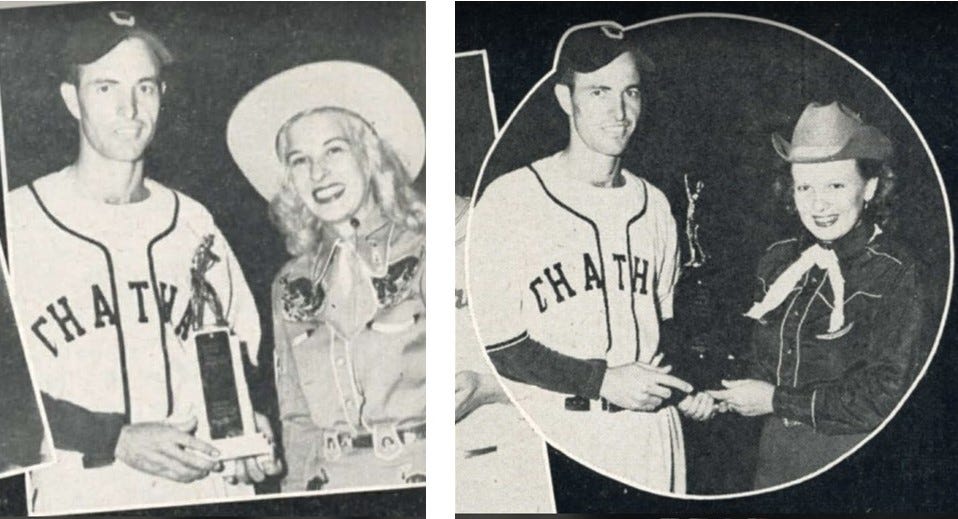

At age 28, Veo Story’s professional baseball career was over, but his baseball career had one more shining moment. He spent the summer of 1948 playing for one of the most successful semi-pro teams in the nation, the Chatham Blanketeers, sponsored by the highly successful Chatham Blanket Company in North Carolina.

The Elkin/Chatham Blanketeers represented North Carolina in the Semi-pro National Tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The Blanketeers were voted the most popular team in the tournament and reached the finals before losing to eventual champion Fort Wayne, Indiana, 2-1.

“Veo Story, the spectacular third baseman of the Elkin Chatham Blanketeers was named as the Most Valuable Player in the Tournament.” - Joplin Globe 1948

Story spent most of his post-baseball career teaching and coaching in Oklahoma. He died in 2007 in Fresno, California.

Note - Special thanks to the Chatham Blanket Manufacturing Company for the photos above.

Nicknames

Nicknames are an integral part of the culture of professional baseball and perhaps one of the game’s most colorful characteristics. When it comes to baseball monikers, one thing is abundantly clear. There is no warm-fuzzy empathy that protects players from alternate identities related to their personality and appearance.

There have been dozens of big leaguers called “Slim,” “Slats,” and “Skinny,” and a few tagged as “Fatty,” “Runt,” and “Pudge.” Players simply called “Lefty” number in the hundreds, but “Righty” seldom sticks as a nickname. Dizzy Dean was not the only major leaguer with an alternate name based on some erratic behavior. There have actually been several other “dizzy” big leaguers, and a 1970s pitcher known for his unpredictability was given the more contemporary sobriquet, “Spaceman.”

Since I plan to do some kind of “Arkansas Nickname of the Month” thing, I have been thinking about the categories of nicknames. There are certainly two major classifications for nicknames. The most lasting ballplayer monikers are those that replace the player’s actual name. Three obvious examples are Preacher Roe, Arky Vaughn, and Dizzy Dean. I would challenge casual fans to name the “real” name of all three, or how about any of them?

Then there are the guys who have a newspaper nickname but were almost never called that name by teammates. Did anyone in the Dodgers’ dugout call Randy Jackson, “Handsome Ransom?” Probably not. What about Lon Warneke? Did teammates ever say, “Good mornin’ Hummingbird?”

Maybe my favorite of these sportswriter nicknames belongs to Robert Fausett, born in 1908 in Sheridan, Arkansas. Teammates likely called him “Buck,” that is one choice. BaseballReference.com replaces Robert with Buck, but claims his nickname was “Leaky.” Come on…in his pretty successful pro career that spanned 18 seasons and more than 2,000 games was he ever called “Leaky” in the clubhouse.

Did you know he is part of a baseball trivia question? When Joe Nuxhall became the youngest pitcher to appear in a big-league game, who did he relieve? Of course, he entered in relief of Leaky Fausett!

You can still order signed books for Christmas delivery.

Book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Great feature as usual. I was certain or at least hopeful, you would have mentioned Grady, “Butcher Boy” Adkins from the late 1920’s

or maybe his great great Grandson formerly at Arkansas Tech, Nick “Ice Cream” Jones.

Thanks for the article on Allen. I enjoyed Martins. As always, I enjoyed your substack! Merry Christmas!