Backroads and Ballplayers #82

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Is it Tommy John Time? - Lost Stories: Pat Seerey Makes History and Another Forgotten Game in Little Rock

Hall of Fame Season Part I

The Classic Baseball Era Committee of the Baseball Hall of Fame will meet on December 8 in Dallas to discuss and vote on the nominations for 2025 induction. Seven players and one manager comprise the eight-name Classic Era ballot, which could include players, managers, umpires, and executives whose primary contribution to the game came before 1980.

Here are the finalists for the Classic Era Committee vote: Dick Allen, Ken Boyer, John Donaldson, Steve Garvey, Vic Harris, Tommy John, Dave Parker, and Luis Tiant. This is a pretty good group. Perhaps good enough to overshadow the guy whose name is more prominent in today’s media associated with a game-changing surgical procedure and a popular brand of boxer shorts.

I think it is Tommy John’s time, but I also think it is Dave Parker’s time, Luis Tiant’s time, and Dick Allen’s time. Negro League outfielder, Vic Harris, became a legendary manager, winning eight pennants in the Negro National League. It seems like Harris has been overlooked. Negro League historians rank John Donaldson as one of the greatest pitchers in an obscure time before the more documented years of the Negro Leagues. Maybe it is time to honor a player from that less publicized era.

There has been significant support for Garvey since he was dropped from the writers’ ballot in 2007, and of course, he played in the bright lights of LA. If I had a favorite Cardinal from my transistor radio days, it had to be Kenny Boyer. Boyer was an 11-time All-Star selection and the 1964 National League Most Valuable Player. He is a sentimental favorite in these parts.

Some of these guys are not going to be selected.

Since the number of career pitching wins “required” for a starting pitcher to be considered a “sure Hall of Famer,” began to fall in the last two decades Tommy John’s 288 wins look good enough to me. Is it time for Tommy John to get the call?

Pick a sure thing…

Lost Stories: Pat Seerey’s Big Day, and Black Sox in Little Rock

Pat Seerey

Regardless of your affection for baseball, there is a pretty good chance that you have never heard of James Patrick Seerey. He did not look like a baseball player, his manager was not sure he belonged on his team, and his career accomplishments are lost in time among more famous Arkansas major leaguers.

Seerey came out of Little Rock, Arkansas, with a charming southern accent, a soft middle, and a likability factor that was off the charts. Fans loved him. He swung from his heels and occasionally hit home runs, often with flair and drama.

James Patrick Seerey was born in Oklahoma in 1923, but his family moved to Arkansas when he was a child. Seerey was a much-heralded football player at Catholic High School in Little Rock, a strong lumbering youngster when 5’10’ and 200 pounds was a big high school footballer. His best sport, however, was baseball, where he got pro scouts’ attention playing for an outstanding American Legion team in Little Rock known as the Doughboys.

In the spring of 1941, before his high school graduation, Seerey signed a pro baseball contract with the Cleveland Indians. The Indians rushed him off to spring training just after his 18th birthday. By the time the senior class of Little Rock Catholic High received their diplomas, their classmate Pat Seerey was playing pro baseball. He received his diploma in absentia.

Seerey was outstanding in his first two years of pro baseball, and by 1943 he had been promoted to the Cleveland Indians. Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau was not the guy to appreciate Pat Seerey’s hitting philosophy. The future Hall of Famer they affectionally called “Old Shufflefoot” coached his players that games were won by putting the ball in play and lost by striking out with runners on base. Pat Seerey’s all-or-nothing style did not win the rookie any favor with his manager.

By their second season together, the young outfielder and his manager were a baseball odd-couple. Faced with few viable alternatives due to a shortage of players serving in the military, Lou Boudreau reluctantly played his rotund, free-swinging fan favorite in 101 games. Boudreau led the American League in batting average. Seerey led the league in strikeouts.

Although Seerey and Boudreau were incompatible, the Cleveland fans loved their every-man power hitter. Boudreau enjoyed a line drive off the wall. Seerey saw that wall as an invitation to hit a fly ball over the barrier that would lead to a leisurely trot around the bases. It was a tenuous relationship that was destined for failure. By his fifth season with Cleveland, Seerey’s future with the Indians was doomed.

Despite his popularity in Cleveland, the Indians placed James Patrick Seerey on waivers to start the 1948 season. His batting average had fallen to .171 in 1947 and Boudreau was out of patience. After clearing waivers the Indians traded Seerey to the last-place Chicago White Sox. The Associated Press announced the trade in an unflattering analysis of Seerey and his career. “Fat Pat Seerey, who could hit a ball a mile but couldn’t do it often, climbed down the ladder today from first-place Cleveland to last-place Chicago.” Associated Press, 1948

Although he was only 25 years old, Seerey’s career was in a steep decline. He only played about 100 major league games after going to the White Sox. One of those games was among the most outstanding individual performances in big league history. Seerey had experienced some memorable days in his career, but in 1948, those moments in the sun seemed a distant memory.

On Sunday afternoon, July 18, the second-place Philadelphia A’s hosted the last-place Chicago White Sox for a doubleheader at historic Shibe Park. The A’s jumped out to a 5–1 lead after three innings of what looked like a routine win for the home team.

In the top of the fourth inning, things began to improve for the White Sox. Pat Seerey led off the inning with a solo home run to make the score 5–2. After the A’s added another run in their half of the fourth, Seerey hit his second home run—this time a two-run shot that narrowed the A’s lead to six to four.

The A’s scored another run before Seerey batted again in the sixth inning. The White Sox’s new addition added a three-run home run to the two runs the Sox had scored earlier in the inning. Chicago moved ahead 9–7 and Pat Seerey was in the midst of another historic adventure.

The game entered the ninth inning tied at 11, and, with the home crowd on its feet, A’s pitcher Joe Coleman walked Seerey to load the bases. A harmless popup to first ended the White Sox’s ninth inning. When the A’s failed to score in the bottom of the ninth, the slugfest moved into extra innings.

Of course, right on script, Seerey hit the go-ahead home run in the top of the 11th inning. At that time, he was the fifth player in big-league history to hit four home runs in a single game. The Sporting News called hitting four home runs in one game “. . . the greatest single-game accomplishment in baseball.”

The 1948 season would be Seerey’s last full season in the majors. He played three more pro seasons including an excellent year in the minors with Colorado Springs in 1950, where he batted .300 and hit 44 home runs. After retirement in 1951, Pat Seerey became a school custodian in St. Louis. He died in Jennings, Missouri, in 1986.

The game has changed significantly since Pat Seerey’s strikeout totals of around 100 were considered unacceptable. In 2021, as a result of an early season trade, the Texas Rangers and New York Yankees combined to pay Joey Gallo six million dollars to hit home runs. He hit 38 home runs but struck out a league-leading 214 times. New York raised his salary to ten million for 2022.

Lou Boudreau died in 2001. In 2004, Topps began posting the newly popular hitting metric OPS on baseball cards. Some baseball stat geeks declared that OPS (On Base% + Slugging%) was the best indicator of hitting success. Boudreau never saw the day coming when an association of hitting statistics would create a measurement that ranked him below Pat Seerey. In 1946, Seerey’s OPS was .804. Boudreau’s was .755.

Black Sox in Little Rock

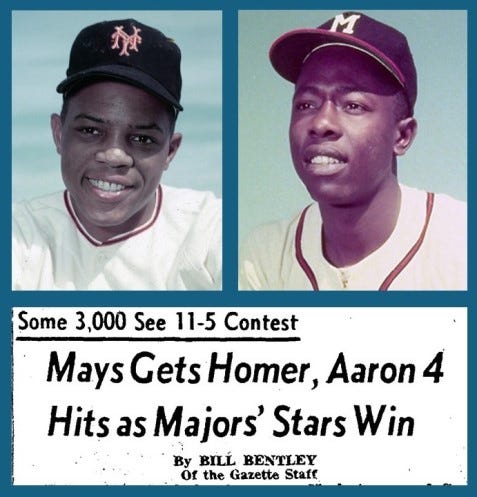

In October, I wrote a feature story in Only in Arkansas about the historic exhibition game in Little Rock on October 10, 1955. I shared the memories of my friend Dr. Joe Whitehead who saw that game in person.

The Black major league team that visited on that Monday of “Texas Week” featured Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Ernie Banks among the dozen or so big-league stars. Only in Arkansas October 21, 2024

That was not the only time some of baseball’s biggest stars played in Arkansas. Thirty-five years before that historic game a group of the major leagues most revered players played a game lost in Arkansas baseball history. Unlike Mays, Aaron, and Banks, many of the players in the 1920 game were about to become among the most infamous men in baseball history.

West End Park was the last stop for the Ninth Street Trolley Line. Little Rock’s most popular public transportation choice took streetcar passengers to 14th Street near the entrance to the park, and from there, it was a short stroll to the ballpark. The park was the home of the Little Rock Travelers, a lake, and a bicycle track. It was the most visited recreational option in early 20th-century Little Rock.

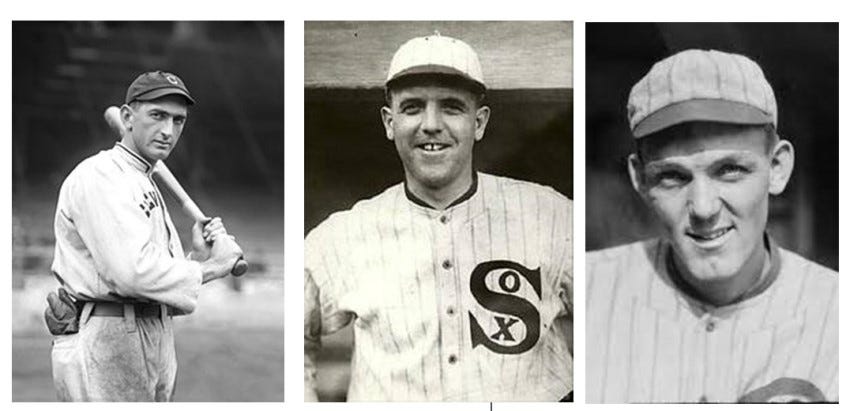

On April 6, 1920, more than 2,000 fans took that ride or walked to West End Park to see the hometown Travs play an exhibition game with the reigning American League Champions.

It was not unusual for major league teams to stop in minor league towns to play exhibition games on their way north to start the regular season. The Chicago White Sox played one of those games in Little Rock on that spring day. The fans attending had no reason to suspect this exhibition game against a team that played in the last World Series was anything other than a chance to see a big-league team in action. In hindsight, the game would be a historic event in Travelers history.

These White Sox were the American League Champions. They were also the team that had lost the World Series six months earlier under suspicion that they consorted with gamblers to throw the series. That day, against the Travs, the big-league stars gave the crowd what they came to see. Shoeless Joe Jackson hit a triple in the first inning, Buck Weaver had three hits in the game, and Happy Felsch had four hits, including a three-bagger. Swede Risberg, a promising 25-year-old, dazzled the Little Rock crowd at shortstop. The White Sox appropriately defeated the home team 10–5.

Jackson, Weaver, Felsch, and Risberg were playing their last season in pro baseball. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis would permanently ban the four in August 1921, along with pitchers Lefty Williams and Ed Cicotte, first baseman Chick Gandil, and infielder Fred McMullen.

No one in Little Rock that April day in 1920 had the insight to imagine they were watching the most infamous team in baseball history. Although researchers examining the same 100-year-old information disagree on the guilt of some of the eight players being banned, and the group was found not guilty in court, Landis’ final decision ended the careers of the men forever known as the “Chicago Black Sox.”

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ballgame; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball. –Kenesaw Mountain Landis, August 21, 1921

More Arkansas Baseball History and Book Ordering Information:

Welcome new subscribers. Stories you may have missed.

Pat Seerey definitely came along at the wrong time in baseball history. Nobody would bat an eye at those strikeouts now as long as he kept hitting home runs.