Backroads and Ballplayers #73

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

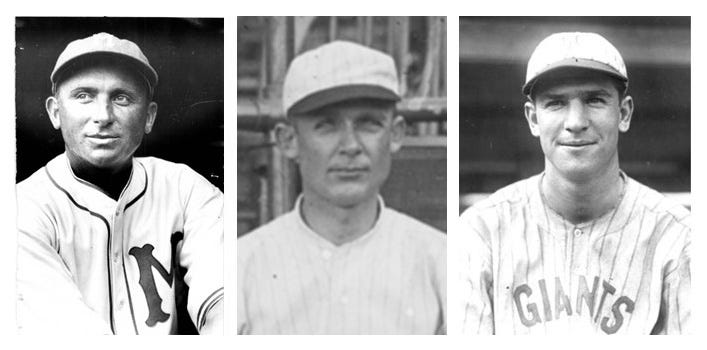

2024 Postseason Begins - Lost Stories: Pea Ridge, Baldy, and the 1924 World Series

Braves and Mets

Just before publishing this post, I watched the first game of Braves-Mets extra-day doubleheader. With the playoffs at stake, it was a classic. No one was miked, and no players were quizzed about their pets or favorite movie while the game was going on. I left the sound on for the entire game. Now Braves, win this one. Both teams deserve to be in the playoffs.

Lost Story: The Triumph and Tragedy of Pea Ridge Day

Now there's some sad things known to man

But ain't too much sadder than

The tears of a clown

-Tears of a Clown - Hank Crosby, Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder 1967

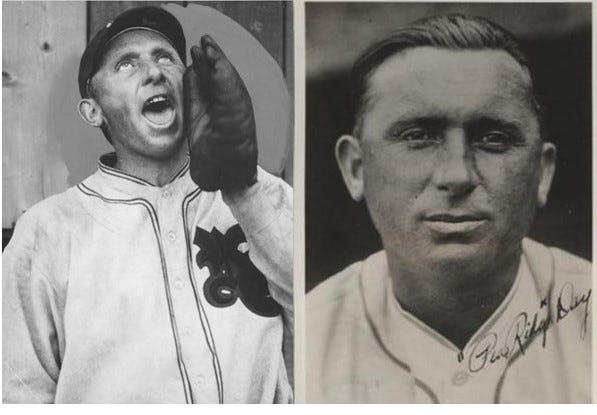

As the baseball season of 100 years ago moved toward its conclusion, a colorful pitcher from Northwest Arkansas, received an expected promotion to the St. Louis Cardinals. The 25-year-old had spent the past three seasons in the Western Association where he was something of a regional celebrity.

Henry Clyde Day's biographical tale is filled with contrasting terms. At times his career and personal life were eminently promising and at other times his future seemed utterly hopeless. His time in the limelight of pro baseball was alternately and often simultaneously comical yet tragic. His hillbilly antics were entertaining but often obscured the real Clyde Day, a clown with a troubled soul.

Henry Clyde Day was born in Southern Missouri in 1899, but he would forever be linked to the small Ozark Mountain town of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, where he grew up. Writers loved the sound of the town’s rural name and soon Clyde Day became known as “Pea Ridge” Day. Not unlike other mountain boys, he hunted, fished, played baseball, and boasted about all three. Day brought this Ozark Mountain bravado with him when he began his professional baseball career.

Day was first noticed by baseball scouts pitching for the town teams of Northwest Arkansas and Southwest Missouri. Some of the attention was for being rowdy, but his local notoriety came mostly for pitching.

After a late-season trial with Joplin in 1921, Day pitched his first full season in 1922 with Fort Smith Twins, a Class D team in the Western Association. The press loved the nickname Pea Ridge but there was little good news to write about Day’s season. He gave up about seven runs a game and finished that forgettable season with a 4-13 record. The next two minor league seasons would be very different from his discouraging first professional season.

Day went 19–14 with Joplin in 1923, and at the time of his promotion in the late summer of 1924, he had won 28 games at Muskogee. Day led the league in pitching victories, but he had pitched an ominous 377 innings, a workload that foreshadowed the sad ending of his career.

Maybe Pea Ridge Day was one of the Cardinals’ most promising minor leaguers, but his story went far beyond his performance on the mound. Ten years before the Dean brothers made the rural Arkansas persona popular among sports writers, Pea Ridge had perfected the character.

Day claimed to be a champion hog caller back home in Arkansas and when he felt the urge he demonstrated his best call on the mound. After a strikeout, an inning-ending putout, or any event he judged worthy, Pea Ridge threw down his glove and let out a high-pitched, prolonged yelp that could be heard blocks away.

Over the next 8 years, his career moved from sore-arm ineffectiveness to moderate success with an assortment of off-speed stuff. After averaging 300 innings per season in his first three seasons of pro baseball, Day averaged less than half that workload for the remainder of his career. As the stress of trying to recapture his place on a big league roster became an everyday concern, the spontaneous hog calls became rare.

Pea Ridge Day reached the big leagues three more times, but the most consistent feature of his later days in baseball was frustration with his chronically sore arm. Despite his reputation as the boisterous hillbilly hog-caller, his skills came nowhere near those of his successful younger days. The bravado of his youth was replaced by failure and depression.

In the summer of 1933, Day’s wife, Lois, announced that she was expecting. His son, Charles, was born in February 1934. Even the birth of his son failed to restore Day’s mental stability. Consumed by the prospect of a dead pitching arm, Day grasped at any hope. Somehow, if he could hold on to the light-hearted image of Pea Ridge Day, things would be better.

For that to happen, he had to pitch. He reportedly spent over $10,000 on arm surgery that did not work, and he began drinking heavily. With his image and self-esteem tied to the character of Pea Ridge Day that no longer existed, he was losing hope, and his despair was spiraling out of control.

In March of 1934, Day somehow convinced the San Francisco Seals to take a chance on him. On his way to California, he stopped to visit an old friend and former teammate, Max Thomas, in Kansas City. While at his friend’s house Day complained of confusion and loss of memory. A local doctor prescribed rest, and Thomas took Day to his apartment to recover. While Thomas unpacked his friend’s bags, Day took his own life.

Henry Clyde “Pea Ridge” Day was buried on March 23, 1934, in his beloved Pea Ridge, Arkansas. He was survived by his wife, Lois, and five-week-old son, John Charles. It was a tragic and shocking end for a man who refused to take baseball seriously. A colorful clown on the outside, Day was greatly troubled on the inside. Pea Ridge Day was 34 years old.

Lost Story: Baldy Earns a Return Trip to the Big Leagues

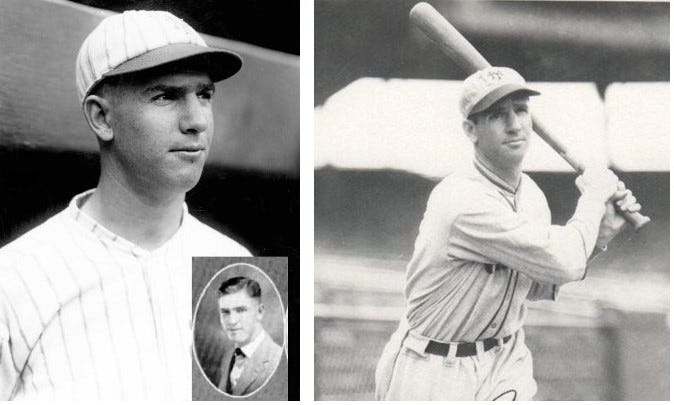

While Pea Ridge Day was getting his first taste of big-league baseball in the final days of the 1924 season, another Arkansas’ adopted son was earning a return to the show after being exiled to the Southern Association two years previous.

Benn Karr was a key member of the rebuilding Little Rock Travelers in 1919 when the September 5 edition of the Arkansas Gazette bid farewell to their home-state favorite.

Bennie Karr pitched his farewell in Little Rock yesterday afternoon – pitched and hit his farewell in the park in which he has made his second start toward baseball fame and baseball prosperity. Little Rock fans will long remember Bennie Karr. Arkansas Gazette - 1919

Karr, a Mississippi native, was destined for a major league shot after his iron man season in Little Rock. “Baldy,” as he was known locally had worked 336 innings for the second-place Travelers. He and Arkansas native Rube Robinson combined to win 44 games. The remainder of the Little Rock staff won 30. On the previous day, Baldy had topped off his 21-win season by winning both ends of a doubleheader. The two complete games took 21 innings for Karr to earn the victories. The season would end the next day, and Baldy was ordered to turn in his gear for the year. He had done enough.

Benjamin Joyce Karr had the typical childhood of professional baseball players of his era. He was born in 1893 and raised on a farm near Mount Pleasant, Mississippi. Although he tried college at Union University in Jackson, when he had the opportunity to sign a pro baseball contract in 1914 he jumped at the chance to “see the world,” he later explained.

It took five unremarkable minor league seasons and a stint in the military during World War I for Karr to reach his breakout season in Little Rock in 1919. In 1920, as the Gazette had predicted, he made the Boston Red Sox pitching staff out of spring training. He remained on the big-league roster for three seasons, although he became disenchanted late in his first major league campaign and attempted to escape the majors for a semi-pro offer. Ironically his AWOL adventure turned out to be a major financial success.

On August 2, 1920, after a relief appearance against the Tigers in Detroit, an unhappy Karr agreed to abandon the Red Sox and join the Oil City Independents semi-pro team in the booming petroleum country of Pennsylvania. He slipped away, boarded a train, and was headed to Oil City when a representative of the Boston club caught up with him at a train stop and persuaded him to return to the Red Sox. In a shrewd bit of negotiating, Karr received a $1,500 bonus for going back to the team that already held his contract.

Three seasons in Boston produced a 16-27 record and a demotion to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. Like his first Southern Association season when he starred for the Travs, Karr was outstanding in Atlanta. He won 21 games in the 1923 season and followed with 23 wins in 1924. After leading the Southern Association in several pitching categories, the Cleveland Indians summoned him back to the majors in 1925.

Now in his early 30s, Karr was no longer the hard-throwing fastball pitcher of his youth. He often relied on a collection of off-speed pitches to keep hitters off balance. His new pitching strategy led to a well-publicized incident in Karr’s career.

According to the prevailing story, Karr was cruising along with a 2-1 lead over his old team the Red Sox in a game in Cleveland early in 1925, when he struck leadoff hitter, Ira Flagstead, just over the eye with an errant fastball. By the time a concerned Karr got to Flagstead, he was on his feet and seemed fully recovered. “Did I hurt you,” Baldy asked. “Not at all,” the Boston player replied. “Well for the love of Pete,” yelled an exasperated Karr, “Lie down will you, it makes my fastball look pretty lousy when I hit a man squarely in the head and can’t hurt him.”

Karr remained with the Indians until 1927. He finished his career by returning to the Southern Association, playing three seasons with New Orleans and finally back with the Travelers in 1931. Karr is among the all-time leaders in pitching victories in the history of the Southern Association, having won more than 100 games during the eight seasons he pitched in the league. Karr finished his career with a major league record of 35-48 in 177 big league appearances. His minor league mark was 122-96.

Apparently, Benn Karr also had fond memories of his time in Little Rock. When his baseball career ended, he returned to Arkansas and began his second career on a farm in Crittenden County near Earle. He continued to make his home in Eastern Arkansas, managing various farming operations until his death in a Memphis hospital in 1968.

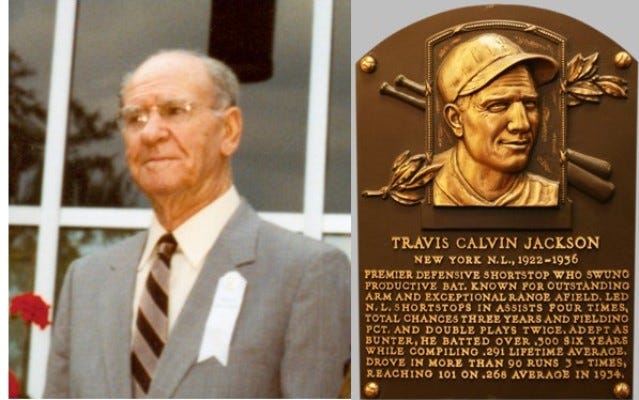

Lost Story From 100 Years Ago: 1924, Travis Jackson’s First World Series

There have been six Arkansas-born major leaguers inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The first of these players to reach the majors was infielder Travis Jackson from Waldo, Arkansas, in Columbia County. Jackson would enjoy 15 outstanding big league seasons. He was in the top-20 vote-getters in the MVP selection process eight times, batted .300+ in six seasons, and finished in the top five in fielding percentage at his position ten times. Despite credentials that merited a place in Cooperstown, the World Series of 1924 was not his finest hour.

The 1924 season was Jackson’s first as a regular, and he did not disappoint. He was still inconsistent at shortstop, but Jackson hit .302 in 151 games, his career-high for games played in a season. While it was a season to remember for the 20-year-old from Waldo, Arkansas, the World Series would not be a fond memory.

The Giants won their fourth consecutive pennant in 1924 and lost their second World Series in a row. The Washington Senators won the series in seven games behind a 12-inning pitching performance by 36-year-old Walter Johnson in the deciding game.

Jackson’s 1924 World Series was a nightmare. He hit .074 for the seven games (two singles in 30 plate appearances) and committed a costly error in the 12th inning of Game Seven.

Travis Jackson would eventually win a World Series ring with the Giants in 1933. His career batting average in four fall classics is .222.

Christmas season special on signed books: Link to book ordering page.

As you can see, Hard Times and Hardball is a favorite at beaches throughout America. This candid shot of a reader comes from blogger Darin Watson creator of U. L.’s Toothpick.