Backroads and Ballplayers #70

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Out on old 10!

A series of potholes and asphalt patches called “Old Highway 10” is all that remains of one of Arkansas’ most traveled early 20th-century routes. Old 10 parallels the newer Arkansas Highway 10 and a section of seldom-used railroad tracks for approximately 20 miles in eastern Yell County and western Perry County.

You can drive from Ola to Casa on Old 10 and not meet another motorist, but you can’t make that solitary trip without imagining what life was like when this neglected stretch of asphalt was a busy highway. It doesn’t take much nostalgic inclination to know there are hundreds of stories out on Old Ten. One of them is about a member of a baseball hall of fame.

A Hall of Famer From Rutland!

My friend Ricky Kimzey, a beloved educator in those parts, surmises that a wide place in the road about three miles out of Ola on Old 10 is the location of a once-thriving railroad community called Rutland. Clues indicate that Ricky is correct. There is no railroad depot in today’s Rutland, no stores or residences, and no sign proudly declaring that Rutland, Arkansas, is the birthplace of a baseball Hall of Famer.

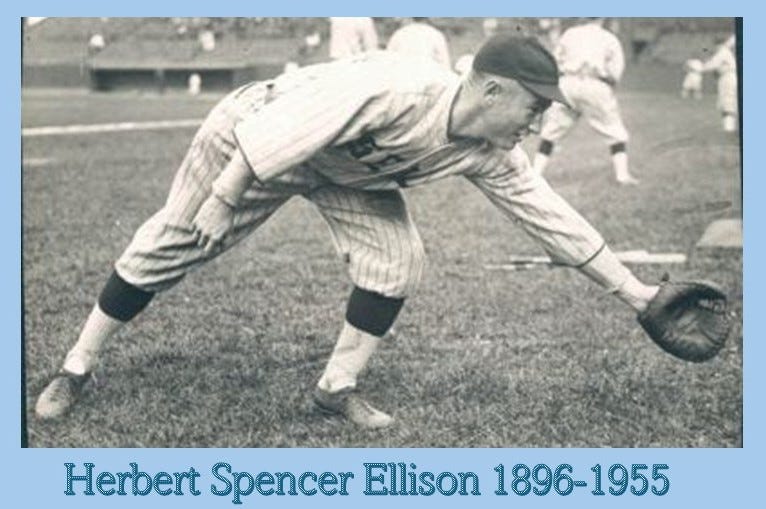

The baseball star’s name was Herbert Spencer Ellison. He was born in Rutland on November 15, 1896. When his father died before Herbert’s second birthday, he and his mother moved to his grandfather’s farm just west of Ola on Ola-Plainview Road.

Young Herbert’s grandfather, John Sandlin, was a prominent farmer in Yell County, Arkansas. Sandlin’s descendants became lawyers, teachers, and farmers who continued to manage the family farm for several generations. His grandson, Herbert Ellison, became a professional baseball player. Although his major league career was less than distinguished, Bert Ellison became one of the most celebrated minor leaguers of the early 20th century.

In the fall of 1914, the Sandlin’s young grandson enrolled at the University of Arkansas with the hope that he would become satisfactorily credentialed to assume a role as a prominent Yell County citizen. At the U of A, they called him “Crook,’ and, while he did not obtain a degree that assured his stature back in Ola, he did become the most illustrious member of the Razorback baseball squad.

The 1916 Razorback yearbook promoted Ellison as a highly regarded big man on campus. “Crook still retains the reputation of being the heaviest hitter on the team. His popularity led to him being elected captain of the team in 1915–1916. In addition to being a first-class baseball player, ‘Crook’ also has quite a reputation as a lady’s [sic] man.”

Ellison never assumed the role of team captain for the 1916 college season. In late spring, after the 1915 Razorback season ended, he signed his first professional contract with the St. Louis Cardinals and joined the Clinton Pilots of the Central Association. Bert Ellison was 18 years old.

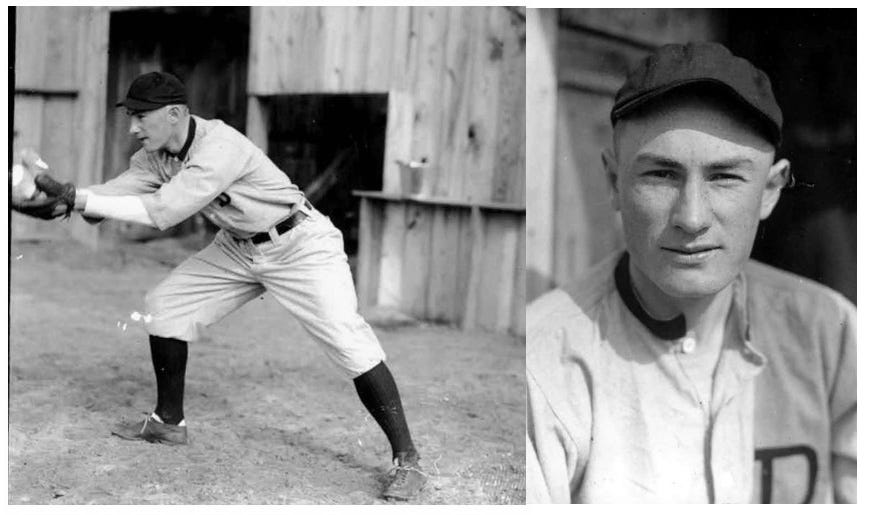

Despite his age, Ellison spent just short of two years in minor league baseball before getting his first major league shot. Both teams were in the Central Association. He played the 1915 season for the Cardinals farm club in Clinton, and after a late-season trade to the Tigers, he spent his second minor league season just down the road in Muscatine, Iowa, in the Detroit farm system.

Although Ellison was the youngest player on the Muskies squad, he led the team in most offensive categories, including 16 triples, and 46 two-base hits. His .361 batting average was the best in the Central Association. At age 19, Bert Ellison had earned a major league trial.

Detroit promoted their teenage prospect from Class D directly to the major leagues on September 1, 1916. In less than two complete minor league seasons, Bert Ellison had gone from college shortstop for the Arkansas Razorbacks to a major league team that featured future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb and Harry Heilmann.

The Tigers were a contending team in 1917. They had finished the 1916 season just four games behind the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox and expected to be in the middle of the pennant race again in 1917. With Cobb, Heilmann, Wahoo Sam Crawford, Arkansan George Harper, and other veterans, Detroit did not have enough playing time for their 20-year-old prospect.

Ellison was assigned to the St. Paul Saints of the Class AA American Association. Once again, he was the only regular under the age of 21, but this time the roster was made up entirely of big-league prospects. Every member of the 1917 Saints would eventually play in the majors.

In a league that featured Hall-of-Fame pitchers like Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown and Dazzy Vance, Ellison hit .278 with power. His 22 three-base hits led the team. The Tigers, once again, promoted him to the big leagues in late September.

Ellison hit two triples and drove in three runs in his first game with the Tigers, but the good beginning was not a sign of success to come. He had only three hits in his last 25 at-bats, and although one of the three was a home run, he seemed outclassed by American League pitching.

Still unproven as a big leaguer at age 21, Ellison was expected to be reassigned to the minors for the next season, but conventional baseball wisdom did not apply in 1918. With hundreds of professional baseball players on active military duty in the World War I mobilization, players were evaluated differently. In early March, after being turned down for the Naval Aviation program, Bert Ellison looked good enough to the Tigers to make the opening-day roster.

The 1918 Detroit Tigers opened the season with Ellison in right field. He was batting a weak .167 with no extra-base hits on April 25 when the Yell County draft board notified him to report for active duty. Ellison missed the remainder of the season except for three games in August while on a furlough before going overseas. He finished 1918 with a .261 batting average in seven total games.

Ellison would remain on the Tigers roster for the next two complete seasons as a utility player. He played 55 games in 1919 and 61 in 1920. On November 17, 1920, Detroit gave up on the player who had once been their number-one prospect, trading Ellison to the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League for a pitcher named Bert Cole. The former Razorback had turned 24 years old two days before the trade. Ellison became one of the most renowned players in PCL history, and Bert Cole won 28 games and lost 32 as a Detroit Tiger before finishing his career back in the PCL.

Bert Ellison had played his last major league game. In his 135 games in Detroit between 1916 and 1920, he played every position for the Tigers except catcher and pitcher. His career batting average was a disappointing .216, with one home run and 42 RBIs. The Tigers never saw the real Bert Ellison.

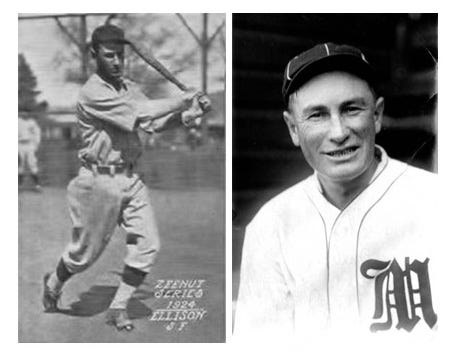

With a fresh start, Ellison regained his confidence and became an instant PCL favorite. A thousand miles from the nearest major league city, the teams and players of the Pacific Coast League were at the top of the sports page news. The San Francisco Chronicle predicted big things for the young man from Arkansas. “Bert Ellison will find himself one of the most popular players who ever pastimed here if he keeps up his present lick in hitting.”

Not only did he maintain his promising start to the 1921 season, but Ellison became one of the Seals’ most productive power hitters. In the long season played in the moderate California sun, he played 171 games, batted .311, and hit a team-leading 18 home runs. Assured that he would be in the lineup every day, Ellison thrived in California.

The 1922 Seals would be named the 44th-best minor league team of all time in a 2001 project by Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright. The Top 100 list was part of minor league baseball’s 100th anniversary celebration. Bert Ellison, who was now the Seals’ regular first baseman, batted .306 with 30 doubles, 10 triples, and 16 home runs. He led the PCL with 141 RBIs.

The Seals won another pennant in 1923, a year in which Ellison’s season totals were extraordinary. He batted .358, hit 23 home runs, 67 doubles, and recorded 271 hits. In September of the Seals’ pennant-winning campaign, San Francisco manager Dots Miller died unexpectedly of tuberculosis. Indicative of the respect he had gained in less than two seasons in the PCL, 26-year-old Bert Ellison became interim manager.

Ellison became the permanent manager of the Seals in 1924. Although the Seals slipped to fourth place, he led the league in RBIs (188) and became one of a select fraternity of professional baseball players to collect more than 300 hits in a season (307).

The 1925 Seals also made the Weiss/Wright Top 100 Teams list (#10). The pennant-winning team finished the PCL campaign with a 128–71 record and went on to defeat the Louisville Colonels of the American Association in a mythical minor league baseball championship series in October.

In 1924, Ellison had added Dick Moudy, a pitcher from his home county in Arkansas, and, in 1925, he made an even more significant Arkansas addition. Smead Jolley, from Wesson in Union County, joined the Seals for the stretch run and hit .447 with 12 home runs in just 34 games. Jolley would eventually become a legend in the PCL and a member of the league’s Hall of Fame in 2003.

Although the 1925 team is generally recognized as the best San Francisco Seals team of all time, Ellison slipped at the plate. His 22 home runs and .325 batting average were down considerably from his performance the previous two seasons. Player-manager Ellison was the toast of the town but managing had taken its toll on San Francisco’s skipper.

A disastrous start to the 1926 season ended Ellison’s managerial career on July 7, with the defending league champions unexpectedly buried in last place. Publicly, the Seal’s manager was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. “Ellison claimed he has lain awake nights of late, trying to figure how to win ball games . . . he contemplates a long rest.”

Ellison took about a month off to collect himself mentally and physically. He rejoined the Seals in early August, and, although he finished the year with a respectable .302 batting average, he was never able to regain the power he had shown the previous five seasons in San Francisco. After playing in just 12 games in the 1927 season, he was traded to the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association where he hit .248 with 4 home runs in 52 games.

A final 79 games as player-manager of the Dallas Steers of the Texas League in 1928 ended Ellison’s baseball career. He was 31 years old. Ellison returned to California where he was an appraiser for the United States Customs Service for 20 years. He died in San Francisco in 1955.

In 2006, Bert Ellison was inducted posthumously into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame.

The Lost Story of Ellison’s Watch

In the fall of 1925, Herbert Spencer Ellison was the most popular man in San Francisco, California. The San Francisco Seals had won the Pacific Coast League pennant and a post-season series with the Louisville Colonels, the champions of the American Association. Since Class AA was the minor league’s highest classification, the Seals justified calling themselves the “Champions of all Minor League Baseball.” The gifts of appreciation presented on “Bert Ellison Day” included an automobile and an engraved gold watch.

Ellison retired in 1928 and spent the remainder of his life in San Francisco. On a trip to Kobe, Japan, in 1933, the watch presented to him on Ellison Day was stolen, and all attempts to recover it were eventually abandoned. The last clue was a tip that the watch had been pawned in China but attempts to contact the buyer were unsuccessful. Ellison had given up on ever locating the watch by 1946 when an interesting mystery resulted in the return of Ellison’s treasured memento.

Young boys walking in a park in Vancouver, British Columbia, came upon a gold watch in a puddle of water. Examination revealed the watch was given as a gift to Bert Ellison in 1925 by the San Francisco Seals baseball team. The youngsters turned the watch over to Capt. Dewey Crowley of the Vancouver police force. The officer contacted President Charles Graham of the San Francisco club to ascertain Ellison’s whereabouts. A few weeks later, the watch was back with its grateful owner in California. According to Ellison, the watch still kept perfect time.

The mystery remains. How did a watch stolen in Japan find its way to a park in Canada 13 years later?

— — — —

Please subscribe to receive these free posts in your inbox or check my Facebook page each Monday evening. Share this post.

Christmas season special on signed books: Link to book ordering page.