Backroads and Ballplayers #69

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Jordan Wicks, Lost Stories: Yell County Part I

I hope each of you had a restful and recharging Labor Day. This post will be brief but it will kick off a series of lost stories from Yell County, Arkansas. If you like the “lost stories,” you will enjoy the adventures of the country boys from the Petit Jean Valley. Next Week - “Out on Old 10.”

It’s More Fun in Person

In case you were watching football, Jordan Wicks is back! I love the continuing story about Arkansas’ young pitchers, Gavin Stone and Jordan Wicks. Not only have they had exceptional rookie success, but more significantly, they have dealt with unexpected adversity as if they were seasoned veterans. Stone struggled in July, but bounced back with an excellent August.

Stone’s feature story Only in Arkansas.

Wicks had his best start of the season on April 23, giving up two runs in six innings in a victory over the Astros. Two days later the Cubs placed him on the 15-Day Injury List with an omonious-sounding left forearm strain. He returned on June 8, but a Grade 2 right oblique strain sent him back to the injury list on June 15. This time he was sidelined about two months before a rehab stint in late August.

What would the Cubs do with Wicks after successful rehab starts in AAA? Many predicted he would spend the remainder of the year in the minor leagues and be faced with making the Cubs starting rotation all over again in 2025. However, in a strong vote of confidence, the Cubs gave Wicks the starting assignment Sunday in Washington and he responded like he had never been away.

Wicks gave up one run on four hits in five strong innings. He threw only 69 pitches and did not walk a batter. It was an impressive start for a pitcher returning from the injury list, but perhaps it was Wicks’ resolve to overcome two devastating injuries in his rookie season that made the most significant impression on the Cubs’ manager Craig Counsell.

Welcome back, Jordan Wicks.

“It’s been exciting watching them. I’ve been tuned into pretty much every game while I’ve been gone,” the southpaw said. “Just to see the way we’re swinging the bats and flying around the field and doing all that sort of stuff is a lot of fun to see and it’s even more fun in person.” — Jordan Wicks MLB.com

Lost Stories: Yell County Part I - A Herring from Dutch Creek

A Herring from Dutch Creek

Not surprisingly, the life stories of many Arkansas rural baseball players from the first half of the 20th century are more interesting than their baseball accomplishments. Often fact and fiction are mixed, embellished, and enhanced in a back story that is difficult to unravel. Such is the case with Herbert Lee Herring of Yell County, Arkansas.

This much we know. “Lee” Herring was born in Shark, Arkansas, in 1886. Of course, Shark is appropriately located in Herring Township about four miles north of Briggsville, as the pelican flies, and eight miles west of Danville. Although located near inconspicuous little Dutch Creek, Shark and Herring Township are undoubtedly several hundred miles from the nearest authentic shark or herring. Regardless of the remote location and incongruous name, Shark has a distinction missing in more well-known communities. The bucolic little village is the birthplace of a former major league baseball player.

Lee Herring, known to his teammates as “Red,” was discovered by Washington Senators’ manager Clark Griffith, a Hall of Famer who had an eye for talent. Herring had caught the attention of one of Griffith’s scouts while playing for a barnstorming Cherokee team from Oklahoma. Predictably, in Herring’s unique story, it is highly unlikely that the Arkansas farm boy had any Native American heritage. However, playing baseball for money undoubtedly sounded better than a hardscrabble farm life on Dutch Creek, so becoming a Cherokee was certainly no obstacle.

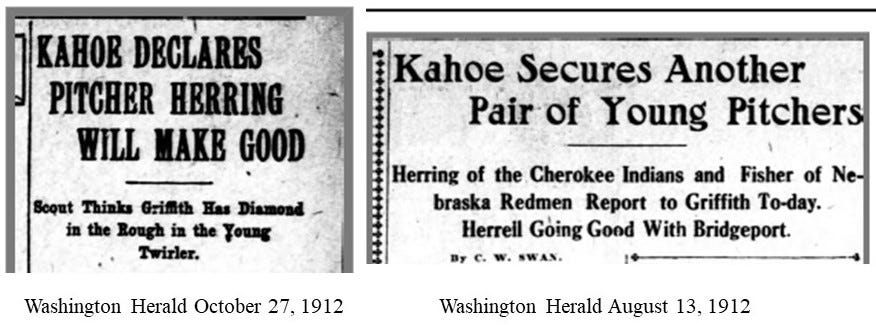

When the Cherokee team played local African-American teams in the Washington D. C. area in late summer 1912, scout Mike Kahoe convinced Herring to stay in town until the Senators returned from a road trip so Griffith could take a look. After all, locals who saw him pitch said he had all the makings of a “corking good pitcher.”

About that time, Herring may have decided his future in baseball would be brighter if he were a few years younger. Although the census of 1900 lists his birth year as 1886 and his age as 13, Herring apparently felt more attractive as a prospect if he assumed his brother Joe’s birth year of 1891. As a result of his decision, he conveniently became five years younger. This new birth year was accepted without question and became the date of his birth on all his baseball records.

Griffith kept Herring around for the next few weeks to take a look or to be entertained. The brash young pitcher exuded confidence and told everyone within earshot that he was ready when Griffith called his name. Among his boasts, Herring claimed to have a double spitter, some sort of saliva-induced delivery that broke in all directions. When Griffith, respectfully known as the Old Fox, described the pitch to Washington writers, they dutifully bought the entire package and predicted the young “Cherokee” would be almost unhittable.

On September 4, 1912, Herbert Lee Herring got the nod from Griffith and took his place in major league history and Arkansas baseball lore. The Senators were 13 ½ games out of first place going into the Wednesday game with the Boston Red Sox, and, while not mathematically eliminated, they were certainly out of the race. This was a good time to evaluate some talent. With nothing to lose, Griffith decided to pitch some rookies, among them the brash “twenty-year-old” with the new birthday and the wicked double spitter. When called on in the 8th inning, Herring gave up one hit and a walk, but no runs, in his one inning of work. No Red Sox batter hit the ball out of the infield. He must have thought he was on his way. Little did Herring know that his major league career was finished. His career record would stand forever as one game and one inning.

In December 1912, Griffith decided Herring could use some work in the minors and farmed him out to the Atlanta Crackers, but he was cut before the 1913 season began. Manager Bill Smith of the Crackers must have been disappointed in what Clark Griffith mistakenly thought was a promising young prospect. Smith sent him farther down the ladder looking for work, and Herring appropriately landed with the Waycross Georgia Blowhards, where he hit .175 and pitched in 18 games in a brief trial.

In keeping with his borrowed birthday and unpredictable personality, Lee Herring decided to use his brother’s name during his minor league days in Georgia. While Herbert Lee, now “Joe” Herring, was pitching in the Empire State League, the real Joe Herring was a live-in farm hand back in Yell County. Lee Herring resurfaced again in Fort Smith in 1915, had some moderate success, but was released in late July after what was described as a “row” with manager Bubs Mosley.

By 1916, Herbert Lee Herring was out of the headlines and pitching semi-pro games in the Western Arkansas League. After his baseball career was over Herring made his home in Bauxite, Arkansas. He later moved to Arizona where he died in April 1964.

Shark, Arkansas, is now in the Ouachita National Forest, and Herring Township has few residents. There is no sign on Highway 80 designating Shark, Arkansas, and no billboard boasting that Shark is the home of former major leaguer, Herbert Lee “Red” Herring.

Please subscribe to receive these free posts in your inbox or check my Facebook page each Monday evening. Share this post