Backroads and Ballplayers #68

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Encounters with the Babe!

A Day with Frank, and Lost Stories: Arkansans and the Babe

Our guest speaker for the annual Robinson Kell SABR meeting at Hot Springs Baseball Weekend was Frank Amoroso a Babe Ruth “scholar” with a twist. He has created a series of Babe Ruth stories based on fact, but not bound by it.

I have a theory about “historical fiction.” To write creative stories about real people and actual events, the writer has to be more precise than those of us who rely on the retelling of well-known tales.

It was obvious that Frank Aromoso was not satisfied with telling the same Babe Ruth stories that have been part of the Bambino saga for decades. He dug deeper and found a more complete Babe Ruth or some would say “created” a more complete Babe Ruth story.

Frank was the featured speaker at our annual Hot Springs Baseball Weekend meeting. He was entertaining, knowledgeable, and often humorous. If you did not attend Frank’s presentation at Hot Springs Baseball Weekend, you can order his Wopper series and his other books on Amazon. Link

Frank mentioned several Arkansas-born players who are part of the Babe Ruth story. Two of my favorite Arkansas players from that era were born about 15 miles apart in the shadow of Mt. Magazine.

Aaron Ward, from Booneville, got the first hit by a Yankee in the new Yankee Stadium, a single in the bottom of the third inning on April 18, 1923. Second baseman Ward was batting seventh in a Yankees’ lineup that included Babe Ruth batting third and playing right field. Later in the same inning, Ruth hit the first homer in what is now known as Yankee Stadium I. The Great Bambino got the headline. Ward got a box of cigars.

Johnny Sain threw the last pitch to Babe Ruth in an organized game. During World War II, Sain was a Navy aviator and pitched for a military team that played an exhibition game against a group of major leaguers at Yankee Stadium on July 28, 1943. Sain walked Ruth who was then 48 years old.

The stories that link Johnny Sain and Aaron Ward to the Babe are staples in baseball trivia games. Who was the last pitcher to face Babe Ruth in an organized game and who got the first hit by a Yankee in the the original Yankee Stadium?

Two similar stories involving the Babe and Arkansas-born pitchers are not as familiar, although one was born in the same community on the Yell County side of Mt. Magazine.

Lost Stories: Jimmy Walkup and Orville Armbrust meet the Babe

“Lefty”

Checking the records for a pitcher named Jim Walkup of Havana, Arkansas, is not a simple thing. BaseballReference.com has the career record of two major leaguers named Jim Walkup and both are from Havana, Arkansas. James Huey Walkup known as Jimmy in Havana and “Lefty” in the baseball world, was born in 1895 and is the cousin of James Elton Walkup who was born in 1909. The younger Jim Walkup is “Elton” back in Yell County.

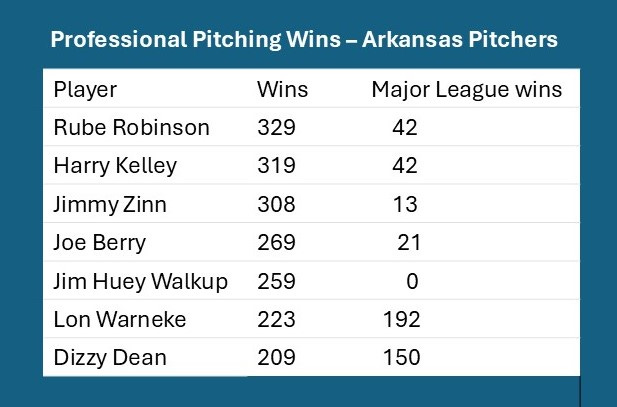

Lefty Walkup is also the answer to a much harder baseball trivia question: “What Arkansas native has the most professional pitching victories without a single major league win?” Walkup’s 259 professional wins over a 17-year career ranks fifth in pitching victories among Arkansans. He is, however, the only pitcher in the top 15 Arkansas natives in that category without a major league win.

Jimmy Walkup pitched in hundreds of professional baseball games and thousands of innings. Only two of those appearances and less than two of his total innings-pitched were in a major league game.

Lefty was a star in the Western Association for seven seasons, before and after his service in World War I. During those years he pitched for Muskogee, Oklahoma City, Joplin, and Okmulgee, winning more than 90 games before he was promoted to Fort Worth in the Texas League in 1924. At Fort Worth, he continued his success, winning a combined 41 games in 1925 and 1926.

Walkup remained with the Fort Worth Panthers until 1930 except for his brief major league visit in 1927. Fort Worth was on a run of great teams during the 1920s. Many of those teams are ranked among the best minor league teams of all time. Walkup would win more than 100 games in the Texas League, and he was perhaps the best control pitcher in league history. In more than 1,500 innings pitched, he walked just 276 batters, an average of 1.6 per nine innings.

The little lefty got hitters out with control, finesse, and breaking pitches. He seldom threw anything that resembled a fastball. On one occasion, while with Fort Worth, Walkup faced Babe Ruth three times in an exhibition game. The Babe fanned all three times. A miffed Ruth angrily downplayed Walkup’s success against him, “I can kick’em up there faster than he throws, that’s why I am in the big leagues and he ain’t.” Despite Ruth’s evaluation, Walkup had all the promise of a future major leaguer, and in late spring of 1927, he got his one and only chance with the Detroit Tigers.

Walkup’s stay with the Tigers was brief, but one of his two appearances was against the greatest team of all time, the 1927 New York Yankees. It was Monday, May 16, and the wind off Lake Michigan brought a winter-like chill to Navin Field. Sunday’s game had been snowed out, and only about 4,000 brave fans rattled around the spacious stadium for the last game of the series. Of course, most were there to see Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the other stars of what would be historically ranked as the best major league team of all time. Even the mighty Yankees could not entice more fans on a day James Harrison of the New York Times declared those attending “should have had more sense.”

The Yankees were one month into a season that would become legendary and a benchmark for measuring great teams in the future. It would be remembered as Babe Ruth’s signature season. and the Yankees of 1927 would become a team for the ages. Yankee fans who later followed DiMaggio and the Mick, Reggie, and A-Rod could readily recite the lineup of the ’27 Yanks.

The batting order on that May afternoon featured Combs and Koenig at the top of the lineup, followed by “murderer’s row” of Ruth, Gehrig, Meusel, Lazzeri, and Jumpin’ Joe Dugan. This was a lineup that would set a standard for intimidating pitchers for years to come. On this mostly ignored and inauspicious stage, a little lefthander from the foot of Mount Magazine, Arkansas, would make his final appearance in the “show.”

Lefty had pitched the last inning of a game with the Cleveland Indians two weeks earlier and had given up a run in the 9th in a 6–2 loss. On this cold day in Detroit, Jim Walkup would come face to face with baseball history’s most legendary heroes and exit the big leagues forever.

The Bronx Bombers had scored four runs entering the ninth. In the third, a homer by Lou Gehrig was followed by a single by Bob Meusel who proceeded to steal second, third, and home. The Yanks added two more in the 7th on a sacrifice fly by Ruth and a double by Gehrig. The Tigers scored two runs in the first and entered the ninth inning with some hope of overcoming a 4-2 deficit.

George Smith had pitched a successful 8th against the Yanks but the 9th would be far different. Catcher Pat Collins walked to start the inning. Pitcher Dutch Ruether, a good-hitting pitcher, batted for himself and grounded out. Smith proceeded to walk Earle Combs and Mark Koenig to load the bases. At this point, Tiger manager George Moriarty called for the little lefty from Arkansas.

Jimmy Walkup stood only 5’8” and weighed in at about 150 pounds, hardly an imposing stature for pitching to the likes of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. With the bases full of Yankees, that is exactly what faced Walkup that unseasonable spring day in Detroit. The Great Bambino may not have remembered Walkup’s success in the exhibition game a few years earlier. This time he greeted Walkup with a single, scoring two runners the little lefty had inherited from Smith.

Somehow the youngster righted himself and ended the inning with harmless pop-ups by Lou Gehrig and Bob Meusel. Jim Walkup’s part of history would be relegated to a line in an obscure box score in the Yankees’ glorious 1927 season.

Looking back, however, through the perspective of Arkansas baseball history, the story of Jim Walkup has a much larger place. The odds against a youngster from Havana, Arkansas, making the major leagues are overwhelming at best, but to have that small moment in time on the mound facing Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig gives Walkup’s last major league appearance a unique significance. The runs that scored on Ruth’s single were charged to Smith, therefore Walkup’s official line for the 2/3 inning’s work against the Yankees would show no runs allowed.

If the story of Jim Walkup’s baseball career ended on that cold day in 1927, it would be an intriguing story, but only the story of his major league career ends that day in Detroit. Walkup, like so many young hopefuls in those days, was a baseball player by profession. He would return to the minors and win more than 100 games in the next eight seasons. Most of that time, he was back with Fort Worth in the Texas league where he was a bona fide star.

Walkup retired in 1934 with 259 minor league wins, one of only a handful of Arkansans with more than 250 career wins. The year Jimmy retired, his cousin, James Elton Walkup, made his first appearance with the St. Louis Browns.

James Huey Walkup died at age 95 in Duncan, Oklahoma.

Arkansas’ Orville Armbrust Spoils Babe’s Last Game as a Yankee

On September 30, 1934, in the season’s final game, Babe Ruth played in a Yankee uniform for the last time. Coincidently, the Washington Senators’ pitcher that day was pitching his last major league game without the fanfare of Ruth’s departure. The Senator’s rookie hurler was only 26 years old and it was his third appearance in his first major league season. While those in attendance knew that at 39 the Great Bambino was finished as a Yankee, few suspected the rookie was making his last appearance in the big leagues.

Legendary sportswriter Shirley Povich described the historic significance of the day in the elaborate hyperbole that made him famous.

The Babe bowed out yesterday.

The end of a 22-year trail, strewn with records fashioned by his bludgeoning bat, greeted Babe Ruth at Griffith Stadium where 12,000 assembled to watch the King of Diamonds abdicate. It was his last game as a regular with the Yankees, a voluntary relinquishment of his post.

Babe bowed out as a loser, what with the Yankees dropping a 5-3 decision to the Nats, but no single defeat could mar the memory of the Big Fellow's deeds of the past, which, after all, were the excuse for the party.

Belongs to Ruth

Nor did the fact that Ruth's potent bat failed to ram even as much as a single to the outfield terrain against Washington's rookie pitching, cloud Washington's tribute to the Big Fellow. The show belonged to Ruth, as fans who turned out for the ball game, as meaningless as an icicle in Little America, attested.

Shirley Povich, Washington Post, 1934

The Washington rookie pitcher on that historic day was Orville Armbrust, a right-hander in his third major league game. Armbrust was born in Bierne, Arkansas, a timber town a few miles south of Gurdon. His father, a sawmill operator, later moved his family to Crossett, another Arkansas lumber town near the Louisiana border. Armbrust had risen quickly through the Senators’ minor league teams at Memphis and Chattanooga, and the big club wanted to take a look at him at season’s end.

Armbrust had made his debut on September 18 against Cleveland and tossed 2 2/3 innings of scoreless and hitless relief. He appeared again on September 24, against the Philadelphia Athletics, and held the A’s scoreless in his three innings on the mound. On September 30, the Yankees would choose future Hall of Famer Red Ruffing to start in Ruth’s last game. The Senators’ manager, Joe Cronin, countered with the 26-year-old rookie, Orville Martin Armbrust, from the Piney Woods of South Arkansas.

The visiting Yankees sent up Frank Crosetti, Red Rolfe, and Ruth in the first inning. If Armbrust was intimidated, he disguised it well. In an otherwise uneventful inning, Ruth stroked a well-hit line drive to center for the third out. After the Senators failed to score in the first, the Yanks put a run on the board in the second on a home run by Lou Gehrig. The Yankees scored again in the 4th inning when Ruth walked and scored on an RBI double by Twinkle Toes Selkirk. Down 2–0, the Senators exploded for 5 runs in the bottom of the 5th. The big blow was a bases-clearing triple by right fielder Johnny Stone. Armbrust faced Ruth again in the 6th and retired the Babe on a routine ground out, although the Yanks picked up another run.

After a routine 7th inning, Cronin relieved Armbrust to start the 8th. The Sporting News reported later that Armbrust had suffered an elbow injury in the game, although such an injury was not mentioned for the remainder of his career.

Tommy Thomas pitched the last two innings for Washington, logging his only save of the year. Armbrust’s pitching line for the day was 3 runs, on 7 hits, in 7 inning’s work. He was the winning pitcher. The game made headlines in newspapers throughout the country, not because of the importance of the game, but because it was The Babe’s last game as a Yankee.

Armbrust’s career was off to a promising start. He had won 22 games in the less than two minor league seasons it took him to get to the majors. He was called up in mid-September of 1934 for a 12-day stay on the Washington roster. In his final appearance with the Senators, he beat the Ruth/Gehrig Yankees and outpitched a future Hall of Fame pitcher. In his three pitching outings with the Senators, Armbrust posted an excellent 2.13 ERA in his 12-plus innings on the mound. Inexplicably, he never pitched in another major league game.

After a very successful late September in Washington, Armbrust was definitely in Washington’s plans for 1935. Manager Clark Griffith spoke well of Armbrust with some serious reservations. An Associated Press article in early 1935 summed up the manager’s concerns. “Griffith likes everything about Armbrust except his avoirdupois. The fat boy has been shaking off weight all winter and may be down to a normal weight by spring.”

The Senators trained in Biloxi, Mississippi in the spring of 1935, and when the team broke camp to head north, Orville Armbrust was sent back to his previous minor league home at Chattanooga. He should not have unpacked his bags. Armbrust made five team changes during the 1935 season. He started the season with Chattanooga. He also spent time with Albany, Harrisburg, Elmira, and back to Harrisburg for the last two months of the season

According to BaseballReference.com, Armbrust’s record for 1935 was 8–14, although five team changes and incomplete stats with some of the teams, call into question the accuracy of his record. Bouncing around the minor leagues would be the story of Armbrust’s career.

Armbrust started the following season with the Dallas Steers in the Texas League but was released in late June and picked up by Galveston in the same league. Armbrust was a combined 7-10 with the two Texas League clubs in 1936.

In what would be a rare year of stability, Armbrust pitched the entire 1937 season for Galveston. His 10–14 record and 4.88 ERA were unimpressive, and 1938 saw him demoted again. This time he was sent down to Class B Jackson, Mississippi of the Southeastern League. Ironically, with no chance to ever reach the majors again, Armbrust had a good year with Jackson. At age 30, he was the oldest pitcher on the team, but he finished with a respectable 15–8 won/loss record, and he pitched the second-most innings on the team.

On March 14, 1939, a relatively insignificant sports story was tucked away in the corner of the baseball news of the day. It took just over three lines of print to announce that Jackson had given Orville Armbrust his outright release. Armbrust retired from baseball, moved to Mobile, Alabama, and worked in the shipyards until he died in 1967. He was 59.

Orville Martin Armbrust, the sawmill operator’s son from the woods of South Arkansas, pitched in one of the most watched games of 1934. In these media-rich days, Babe Ruth’s last game as a Yankee would have been nationally televised, and the game would have been the lead story on Sports Center. A crew would have been dispatched to Arkansas to interview Armbrust’s family, and baseball fans would be diligently watching his tweets. In 1934, it was beloved sportswriter Shirley Povich’s job to watch the game for the thousands of fans who had no other way to witness the historic event. Fans “saw the game” the next day through Povich’s eyes and his flowery prose.

And then he went into the ball game. But no semblance of a base hit bounced off his lusty bat. The rookie pitcher, Orville Armbrust, retired him in the first inning on a fly to center field. On his next appearance, he was walked. A harmless grounder to Buddy Myer, he drilled on his third trip to the plate.

In one uproarious assault against Red Ruffing, the Nats won the ball game, blasting a 2-0 Yankee lead out of being with a five-run splurge in the fifth inning. Young Armbrust held that lead.

But that ball game had been only an anticlimax. Unlike Hamlet, the Babe, not the play, was the thing. Shirley Povich, Washington Post, 1934

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link