Backroads and Ballplayers #65

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Hot Springs Baseball Weekend & a Lost Story about “Oil”

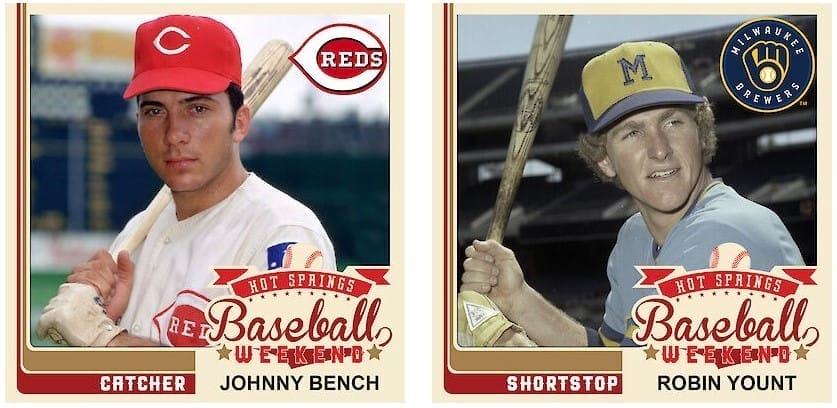

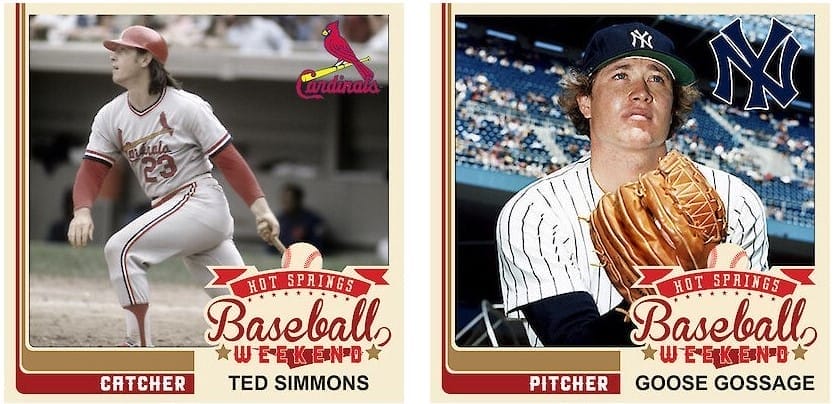

Hot Springs Baseball Weekend begins with evening activities on Friday, August 23, and continues with a full day of Hall of Famers, Sports Collectables, and baseball history presentations on Saturday, August 24.

This week’s Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly features information about the annual event and a lost story about a catcher called “Oil” who grew up in Hot Springs.

One weekend each year Cooperstown comes to Arkansas. Mark your calendar and save the date!

Seventh Annual Hot Springs Baseball Weekend

Hall of Fame Guests, Sportscard Show, Special Showing of “It Ain’t Over,” and skills clinic for young players, all FREE

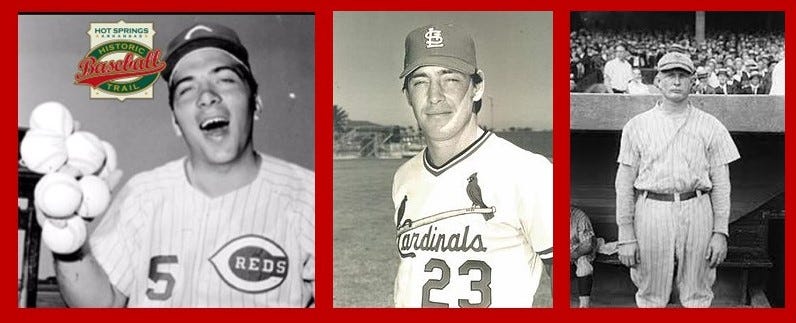

Hot Springs, Arkansas, the “Birthplace of Major League Baseball Spring Training,” will come alive with the Seventh Annual Hot Springs Baseball Weekend, August 23-24, 2024. The late-summer gathering of baseball fans has become one of the most popular weekend sports events in the state. Beginning as a way to share the traditions of baseball in the Spa City, HSBW has become a regional event that brings thousands of baseball fans together for a free weekend celebrating our National Pastime.

Click here for details about Arkansas’ premier baseball event.

After you make plans to visit Hot Springs Baseball Weekend, come back and read the lost story of Hot Springs’ most colorful baseball character.

If you are visiting this column for the first time, my name is Jim Yeager. I am a semi-retired coach and educator. My mission is to share the rich history of Arkansas baseball. This Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly posts every Monday and will always be free.

Lost Story “Oil”

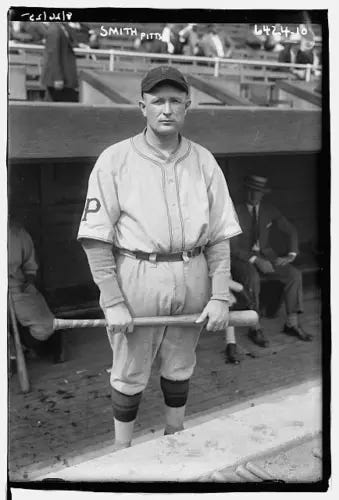

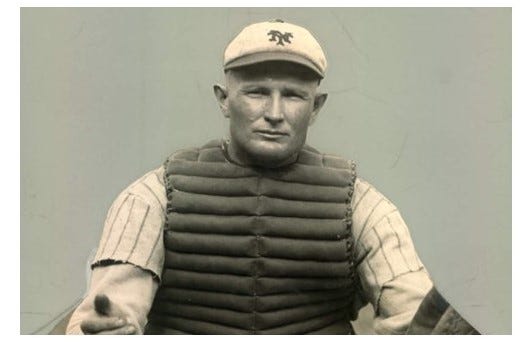

A police detective who attempted to search the private lockers of the New York Giants at Polo Grounds for liquor today had his curiosity curbed by Earl Smith, catcher of the club. Smith refused, demanding to see a warrant. The detective announced that he was acting under orders to make the search and would do so if he had to fight it out. Smith invited him outside at once. After a short and furious encounter in which he got the worst of it, the detective left in a hurry for reinforcements. He did not return. —Philadelphia Inquirer, 1921

Earl Sutton Smith is one of those colorful baseball men whose unrestrained personality overshadowed a good career. Most of Smith’s biographies lead with stories about conflicts, suspensions, and insubordination, relegating a lifetime .300 batting average and three World Series titles to a couple of buried paragraphs. Described as one of baseball’s most notorious fighters, trash talkers, and rule breakers by his detractors, he was competitive, tough, and resourceful to his fans. Throughout a career that spanned 16 professional seasons and 1,159 games, Smith walked a thin line between combative and contemptible.

His nickname, “Oil,” came from the distinct way New Yorkers pronounced Earl, but the volatile nature of petroleum fit his demeanor perfectly. In his obituary, the Associated Press proclaimed, “He probably was involved in more fights than any player in the game and was regarded as one of the most colorful players in the golden era of sports.” Two sentences, four paragraphs down the obituary, reveal that “Smith spent 14 full seasons in the majors and batted over .300 in five of them.” New Orleans Times-Picayune 1963

Earl Smith was born in Sheridan, Arkansas, in 1897, but, after his father died when he was two, the family moved to Hot Springs to live with his grandmother. Smith grew up quickly with horsemen and ballplayers as his role models and toughness as his shield. By age 18, he was making headlines on men’s semipro teams and soliciting impromptu auditions with the pro teams holding spring training in the city.

At age 19, he landed his first minor league job with Waxahachie in the ill-fated Central Texas League. The financially fragile league opened play on April 28 and disbanded on July 24. Smith’s modest .269 batting average led the team.

Following his abbreviated season in Waxahachie, Smith hooked on with the Fort Smith Twins in the Western Association in 1917. Smith’s .332 batting average led the Twins and the league. Uncharacteristically for his contact style of hitting, Smith also added 21 home runs.

Promoted to Rochester in the International League in 1918, the now 21-year-old catcher hit a team-high .358. Smith had proven himself at every minor league level. His next stop was the 1919 New York Giants.

When the Giants came calling with a contract in the spring of 1919, only a free-thinking nonconformist like Earl Smith would say, “No, thanks.” Although he had never played a big-league game, Smith declined the Giants’ first offer and declared himself a holdout before finally reaching a compromise on March 11. The New York Times proposed that “Smith is the first player who was a holdout before he even played.”

In 1919, Earl Smith not only got his first taste of big-league baseball, but he also met a baseball man as stubborn and unconventional as he was. His manager was John McGraw, a short, stocky, emotional fellow, much like Smith in both stature and temperament. The manager known as “Little Napoleon” decided the best way to tame his reckless young Arkansas boy was to bury him at the end of the bench.

The Giants’ new catcher appeared in only four games in the first two months of the season, and, on September 1, he had batted only 19 times. McGraw gave him five starts in September, but the manager had not taught a lesson; instead, he had annoyed an unyielding adversary. Smith posted a .250 batting average in only 40 at-bats.

The 1920 season started with Smith’s place in McGraw’s plans still in doubt. He played in only one of the team’s April games, but with starting catcher Frank Snyder hitting .125 for the month, Smith got most of the work in May. The two catchers split time the remainder of the year, with Smith getting into 91 games and posting a strong .294 batting average. Unfortunately, playing more often meant more opportunities for conflict between a hard-nosed manager and his stubborn young catcher.

McGraw fined Smith $200 on July 10 when the bizarre incident that resulted in a fight with a policeman the previous week turned out to be a thrashing of Giants Coach Cozy Dolan. The detective story, which had appeared in newspapers all over the country, was later revealed to be a coverup. Apparently, to Smith, a tussle with a policeman sounded better than assaulting his coach.

On August 4, 1921, with Smith getting most of the starts at catcher, McGraw suspended him indefinitely for “purposeful poor playing.” Indefinitely turned out to be 10 games. Smith got his starting job back on August 18 and batted .389 for the remainder of the season to finish his year with a .336 mark.

The Giants easily won the pennant and defeated their arch-rivals, the Yankees, to win their first World Series since 1905. During the series, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis got in on the Smith disciplinary action, fining the Giants’ catcher $200 for confrontations with Yankees’ players and umpires. Landis labeled the offenses as “irregularities.”

The 1922 season was another successful year for the Giants and another struggle in the relationship between Earl Smith and his manager, John McGraw. McGraw liked to call pitches from the dugout, a responsibility that Smith felt was the prerogative of the catcher. Often, he refused to look at the dugout and gave the sign without managerial input.

Smith played in 90 games in 1922, a season that saw him suspended, fined, and chastised by the press. Although Smith batted a respectable .278 with only 12 strikeouts in 275 plate appearances, his relationship with John McGraw had reached the point of no return. Once again, the Giants defeated the Yankees in the World Series, but, despite the success, McGraw, whom the press suggested had resorted to “harsh measures,” was nearing an impasse with Earl Smith.

Although there were irreconcilable differences between Smith and his equally obstinate manager, the Sporting News theorized that the final straw was the pitch-calling issue. In a game in early June of 1923, McGraw called for a fastball, and Smith signaled a curve. The batter struck out, but McGraw was livid. “That will cost you $50,” McGraw snarled. “Is that all,” Smith snapped back. “It’s $100 now,” McGraw yelled at the defiant catcher. On June 7, 1923, with no hope of a reconciliation, Smith was traded to the Boston Braves.

Oil Smith became the primary catcher in Boston for the remainder of the year. He finished strong hitting .288 for his 72 games with the Braves. Although he was away from his arch-rival John McGraw, Smith was not happy in Boston, nor was Boston particularly enamored with him. His discontent and some defensive shortcomings led the Braves to sell Smith to the Pittsburgh Pirates in July of 1924 for the waiver price of $4,000.

Representing the blue-collar Pirates’ constituency was an excellent place for the oft-criticized Smith. Like his Pirates followers, Earl Smith was tough, determined, and fiercely competitive. The fans loved him, and his conflicts with opponents and baseball’s leadership made him a Pittsburgh hero.

Smith hit .313 in 1925, his first full year in Pittsburgh. The Pirates won the National League pennant and defeated the Washington Senators in the World Series. Smith batted .350 in the Fall Classic and his constant harassment of opposing players delighted his supporters. “Nobody close to the Pirates in the historic 1925 season doubts that Smith . . . talked opponents out of enough games to bring the pennant to Pittsburgh.

The Pirates fell to third in 1926. Smith hit .346, but he continually irritated opponents with everything from insults to well-aimed tobacco spit. He was a regular on National League President John Heydler’s mailing list, but his abuse of umpires and harassment of opposing players were not deterred by letters from the commissioner.

While he was a hometown favorite in Pittsburgh, Smith’s reputation took a hit in 1927 when he knocked out his former manager Dave Bancroft with an unsuspected punch after the smaller manager had turned to walk away from an argument. Smith drew a one-month suspension and a deluge of negative press. After he served his suspension, he injured himself jumping a fence in Boston to avoid being served court papers in a $15,000 suit filed by Bancroft.

Smith’s adventures relegated him to 66 games in 1927, and, although the Pirates won another pennant, their controversial catcher had become a liability, even in the town that loved him. On July 10, 1928, Smith was released by the Pirates. He was signed three days later by the St. Louis Cardinals. Ironically, the 1928 Cards won the National League pennant.

Now in his 30s, Smith had one more good year in 1929 as a part-time catcher in St. Louis. He posted a .345 batting average in 57 games for the fourth-place Cardinals. Optioned to the minors in 1930, Smith earned his way back to the Redbirds for eight games in September. He hung on for one more minor league season in 1931 that included a brief stop in Little Rock.

Lost in the recounting of Oil Smith’s escapades is the career of an excellent baseball player who played in a time when rural Arkansas men began to make a place in pro baseball.

He played across town in New York from Yankees’ second baseman Aaron Ward. The Ouachita College-educated infielder from Logan County, Arkansas, hit the first home run in Yankee Stadium.

A few years later, 18-year-old Travis Jackson became Smith’s teammate with the Giants in late 1922. Jackson had also attended Ouachita, where he was an accomplished thespian and musician, as well as an infielder. Although Jackson and Ward hailed from Smith’s home state, they could not have been more different from the flamboyant Oil in demeanor.

Ray Powell, “The Rabbit of the Ozarks,” Smith’s teammate at Boston, and Walter Schmidt a former coal miner from Johnson County who shared catching duties with Smith in Pittsburgh, were more in tune with the “outgoing” Smith. Both made a considerable number of sports page headlines that did not involve a baseball game.

In Smith’s last major league game, with another pennant locked up, manager Gabby Street asked him to catch the Cards’ final game of the regular season. On Sunday, September 28, 1930, Oil Smith made his last big-league appearance, catching a rookie pitcher in his first major league game. Dizzy Dean prevailed in that debut, pitching a three-hit masterpiece. Diz’s first game in the show was Smith’s last.

Earl Sutton Smith died in Hot Springs on June 8, 1963. Among Arkansas-born major leaguers with 2,500 or more plate appearances, his .303 career batting average ranks third behind Arky Vaughn and George Kell. He played in five World Series and won three series titles. In the 1925 World Series, he hit .350.

Although he was a backup catcher for much of his career, and most of his notoriety came from his confrontational nature, esteemed baseball historian Bill James once ranked Oil Smith as one of the top 100 catchers of all time. Smith would rank much higher in a list of baseball’s colorful characters.

—————————————————

Save this link for details about Hot Springs Baseball Weekend

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/