Backroads and Ballplayers #64

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

For the Love of the Game, and “Fixing” Baseball

Baseball is indeed a unique game. It is the game of our grandfathers. Likely the first game we played with our fathers, with underhanded tosses, and overdone cheers for any accidental contact. Some form of this game gave us our first chance to put on a uniform and be part of a team. It may have been something called T-ball, Teeny League, or Softball, but we were all dressed alike, mom took a lot of photographs, and the bar for success was low. Foul balls drew cheers, miss-fielded ground balls became home runs, and even losses earned celebrations at the Dairy Queen. We were ballplayers, our dads had been ballplayers, and our granddads had been ballplayers. It was summer, the grass was green, and all was well in the world.

I wore number 7!

“The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It has been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game: it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds of us of all that once was good and it could be again.”– James Earl Jones as Terence Mann in Field of Dreams

An Invitation for Every Baseball Fan in Arkansas

The Robinson-Kell Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research will meet this Saturday, August 3, in Bryant. Membership is not required and guests often outnumber SABR members.

If you enjoy stories about baseball history, you will love this community of Arkansas baseball fans. The meeting will be held at First Southern Baptist Church in Bryant, AR, 604 South Reynolds Road, from 12:00 to 4:30 PM. The meeting room will be at the left end of the building when entering the parking lot.

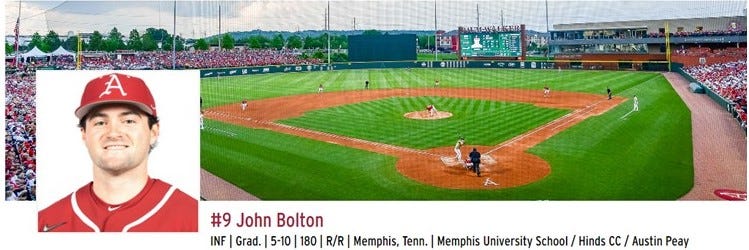

Snacks and soft drinks will be provided. We do have to pay to use the room for non-church events, so $5 donations are encouraged. The guest speaker at this meeting will be John Bolton, the starting shortstop for the 2023 SEC Champion Arkansas Razorbacks. Bolten’s recollections of his time as a Razorback will be followed by several presentations from members and guests.

Each week about 400 of you read Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly. I would love to meet you at Robinson-Kell!

Lost Stories

A week or two ago I read an insightful piece called “Fixing the Game.” The title concerned me, but we have been about fixing the game since the two-league system was born in the early 1900s. Perhaps the most significant of these changes put an end to pitchers altering the ball.

Well, perhaps it didn’t completely end creative ball prep…

“Fixing the Game” - The Last Spitball

“We must look for some legislation before long in regard to the pitcher. We are all willing to concede that he is a plucky, determined Base Ball character, and the very fact that he is so persistent and combative makes it necessary now and then to subordinate him a little to the other men who are part of the game.” — Spalding’s Baseball Guide, 1909

Despite declarations to the contrary baseball has always clandestinely made pitchers the villain. After all, pitchers initiate every action in baseball, and although purists claim to enjoy a one-to-nothing pitcher’s duel, most fans like to see the ball in play or deposited over the outfield fence.

Pitchers, by assignment, are formidable enemies of action and are deemed to have sufficient skills without the help of a foreign substance or a vandalized ball. The rules-makers made their first serious attempt to stop the cutting, soiling, scuffing, and applying saliva, 100 years ago. They made their latest attempt to guard against such mischief in 2021.

Rule 3.01

Players cannot intentionally damage or discolor the ball by rubbing it with foreign substances such as soil, rosin, paraffin, licorice, sandpaper, or emery paper. If an umpire finds a player doing this, they must take the ball and remove the player from the game. The player will also be automatically suspended for 10 games.

Rule 6.02

Pitchers cannot apply any foreign substance to the ball, deface it, or have any foreign substances on or near them. This includes shine balls, spit balls, mud balls, or emery balls. If a pitcher is found to have a foreign substance, they will be immediately ejected from the game and automatically suspended. If another player is found to have applied a foreign substance to the ball, both the pitcher and the position player will be ejected.

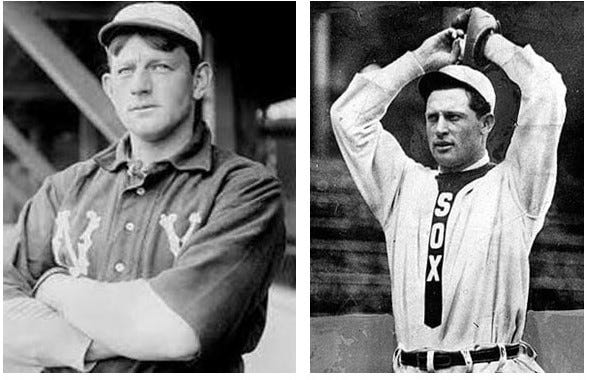

The individual, who first decided to spit on a baseball to see what would happen when it was thrown, is not celebrated as a significant innovator in the game. Perhaps the discovery that salvia, correctly applied, made the ball dart down erratically, was more accidental than scientific. Although the father of the spitball remains uncredited, the first two big-league pitchers to rely on the pitch successfully were Jack Chesbro and “Big Ed” Walsh, who pitched concurrently in the early 1900s and were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame together in 1946. The first Arkansan to reach the major leagues as a spitball artist was a much-traveled baseball journeyman from North Little Rock named Bill Luhrsen.

William Ferdinand Luhrsen was born in Illinois on April 14, 1884, but he called North Little Rock, Arkansas, his home all his adult life. By the middle of the 20th century’s first decade, the Luhrsens were well known around the little city called Argenta. Bill’s brother Louis was an Argenta alderman, and brothers, Bill and George, were getting noticed as semi-pro baseball standouts. Desperately in need of a baseball nickname, young William became known around ballfields as “Wild Bill” Luhrsen.

Baseball-Reference.com credits Wild Bill Luhrsen with exactly 100 professional appearances. Those recorded games all occurred after 1909 and do not include at least as many games played in the Arkansas State League and the Northeast Arkansas League. From 1906 through 1909, Luhrsen pitched for most of the minor league teams in the small cities in his home state. At various times, Wild Bill was the ace pitcher for his hometown Argenta Shamrocks, and teams in Brinkley, Pine Bluff, Marianna, and for the Alexandria, Louisiana, Hoo Hoos, who despite the location, played in the Arkansas State League. In both the 1908 and 1909 seasons, he pitched for three of the above small-town minor league clubs in the same season.

Luhrsen spent seven summers in the fragile world of minor league baseball from 1906 to 1912. In those seasons on the backroads of American baseball, he never started the season with a team that did not cease operations before completing the schedule. Luhrsen and his spitball played in cities in New York, Kansas, Alabama, and Georgia, finally reaching the major leagues in 1913.

Wild Bill started the 1913 season in the low minor leagues at Selma, Alabama but was promoted in mid-season to the Class C Albany, Georgia, Babies of the South Atlantic League. A month later after a combined 17 – 8 record for the season, Luhrsen got the call to report to the major league Pittsburgh Pirates. Among his teammates in Pittsburgh were Future Hall of Famer Honus Wagner, and Future Arkansas Hall of Fame selection Rube Robinson.

Bill Luhrsen was in fast company, but he continued to pitch well in the big leagues. After two starts and a couple of relief appearances, he had won 3 games and lost none, with an Earned Run Average of 2.00. Unfortunately, he was about to meet the greatest pitcher of his day and receive some shocking news.

In his third start on September 13, Luhrsen faced Future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Going against a living legend, in front of a large home crowd, on a Saturday afternoon, may have given Luhrsen a case of stage fright. In the first two innings, he gave up two hits, three walks, and a hit batsman. By the bottom of the second inning, Manager Clarke had seen enough and pinch hit for his rookie pitcher. In fact, despite three wins, only one loss, and a 2.14 ERA, Clarke had decided Luhrsen was not ready for the big leagues.

Wild Bill Luhrsen was traded down to Columbus in the American Association, the highest level of minor league baseball, with a promise that he would return as soon as he worked out some mechanics. Despite the promising debut, Luhrsen never pitched in another big-league game.

The next two seasons would literally be a train ride through the bush leagues of baseball’s back roads for Arkansas’ traveling spitball pitcher. Even for a man with a history of forced travels, the downhill journey from the major leagues through descending levels of minor league baseball and back to Arkansas semi-pro leagues was a disheartening odyssey.

Although Luhrsen was finished as a big-league pitcher, baseball officially banned his best pitch in 1920. After weeks of negotiations, major league baseball allowed 17 exempted pitchers, who depended on the pitch for their baseball livelihood, to continue to throw the spitter until retirement. Fourteen years after the spitball had been banned, a 40-year-old pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates used the last legally thrown spitball to strike out Brooklyn Dodgers journeyman Joe Stripp in a 2–1 Dodger victory.

The pitcher had a suitable name and the villain’s face to oppose a Kevin Costner character in a Hollywood baseball movie, but the end of the spitball melodrama ended without significant fanfare. The virtually ignored date was September 20, 1934, and a sparse crowd generously estimated at 1,000, at Pittsburgh’s old Forbes Field, saw “Ole Stubblebeard,” Burleigh Grimes, throw the last legal spitball in baseball history.

Grimes was the last active member of the 17 rule-exempted pitchers who were allowed to use the spitball. His retirement in 1934 meant the end of the “legally” thrown spitball. Despite the ban on foreign substances applied to the baseball, clever hurlers continued to throw the spitball or other lubricated versions of the slippery sinker. They generally avoided detection and found new and more cunning ways to hide their intent. The deceitful rule-breakers operated without conscience in a game whose rules always seemed to favor hitters.

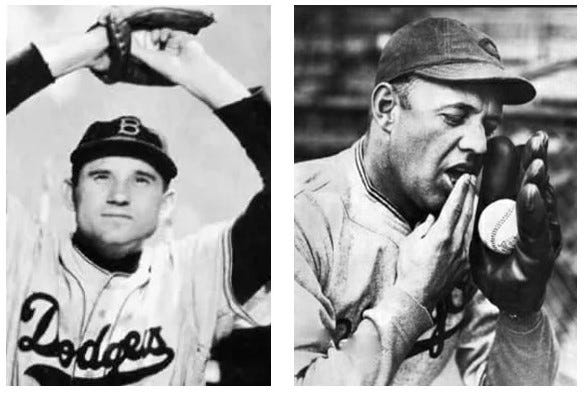

Among those devious hurlers was Arkansas’ Elwin “Preacher” Roe, who admitted after his retirement that he had thrown a spitball at times. The always clever Roe, also revealed he had more success with a fake spitter. After pretending to go to his mouth, cap, belt, and glove to wet the ball, Roe threw a fastball by the confused hitter.

“It never bothered me none throwing a spitter. If no one is going to help the pitcher in this game, he’s got to help himself.” -Elwin “Preacher” Roe, 1955

On June 27, 2021, Seattle Mariner pitcher Hector Santiago became the first pitcher to be ejected from a game for using a foreign substance under the new umpire-search rule of 2021.

“Fixing the Game” - Tris Speaker and The Ray Chapman Incident

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the almost-forgotten story of the year Tris Speaker played for the Little Rock Travelers. Speaker’s biography is the subject of several books, and his accomplishments earned him induction as part of the Baseball Hall of Fame’s second honorees.

Speaker was also part of an incident that resulted in a ban on foreign substances that darkened baseballs and made them difficult to see in the late innings. That unfortunate incident in August of 1920, is a lost story in “Fixing the Game.”

Raymond Johnson “Ray” Chapman (January 15, 1891 – August 17, 1920)

Ray Chapman was already in Cleveland when Tris Speaker arrived in 1916. The good-natured country boy, whom teammates called “Chappie,” would become a personal favorite of the future Hall of Famer and develop into an outstanding major league shortstop. By 1920, player-manager Speaker had given the 29-year-old Chapman the prestigious second position in the Cleveland batting order, just ahead of his third-place spot.

When Chapman led off the fifth inning in the August 16, 1920, game with the Yankees, his friend and manager was in the on-deck circle. Carl Mays, a generally disliked veteran submarine pitcher, was on the mound for the Yanks. The Indians had built a 3–0 lead as the Cleveland shortstop assumed his unorthodox stance. As was his custom, Chappie stood as near the plate as the batter’s box would allow and usually moved away as the pitcher released the ball.

With the count at one ball and one strike, Mays planned to back Chapman off the plate with a fastball inside, but the pitch, rising from the underhand delivery, tailed up and inside to the right-handed hitter. Frozen in the moment, Chapman did not move back this time, and the five-inning-old, discolored baseball struck him in the temple. Babe Ruth said later that he heard the contact clearly in right field and saw the ball roll slowly back toward the mound. Sportswriter Fred Lieb described the sound as a “sickening thud.”

Confused by the crack of the impact, the Yankees originally thought Chapman had hit the ball. With the concerned group of players racing toward the fallen hitter, Mays mistakenly threw the ball to first for what he assumed was a ground-ball out. Seconds later, players from both teams stood in stunned silence as they processed what had occurred.

The 21,000 fans in the Polo Grounds also fell silent, as Speaker and others gathered around home plate. The players found the shortstop out cold, with blood from his left ear trickling down his cheek. The seriousness of the injury was obvious. Umpire Tommy Connolly ran to the stands to announce that a doctor was needed, as Speaker and Yankee catcher Muddy Ruel attempted to revive Chapman. The umpire located a doctor from the crowd, and the Yankee team doctor soon arrived on the scene with ice.

The two physicians revived Chapman in a few minutes, and, along with teammates, slowly walked the injured player toward the Polo Grounds’ center-field tunnel. The crowd politely applauded what seemed to be a more positive outcome than originally feared. Unfortunately, Chapman collapsed again at second base, and teammates carried him to the clubhouse.

Speaker accompanied Chapman to nearby St. Lawrence Hospital and, in the absence of a next of kin, permitted emergency surgery. The surgeons removed pieces of shattered skull and blood clots, but the injury was too significant for the medical technology of the 1920s. The 29-year-old Chapman died the next morning before his wife Kathleen arrived from Cleveland.

On August 20, Chapman’s funeral at St. John’s Cathedral drew scores of baseball dignitaries and thousands of fans and friends. Tris Speaker, reportedly overwhelmed by grief, did not attend.

Ray Chapman remains the only player to have been killed by a pitch in a major league game.

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/