Backroads and Ballplayers #60

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

In Case You Missed It: Feel Good Story of the Week: Heston Kjerstad

Today the Baltimore Orioles are in first place in the AL East by a few percentage points over the Yankees. It would not be too surprising that the hottest hitter in the Baltimore lineup is a promising rookie. Several baseball “experts’ thought it could happen. It might be unexpected, however, that it is not Jackson Holliday, Colten Cowser, or Coby Mayo, the Birds’ top three prospects entering the 2024 season. In Arkansas, we are not surprised that it is Heston Kjerstad. It is about time, but certainly not unexpected.

In the Razorback’s16-game 2020 season cut short by the Covid nightmare, Kjerstad had at least one hit in every game. He was leading the SEC in slugging percentage (.791), home runs (6), and total bases (53), when the season abruptly ended on March 17. Kjerstad was batting .448 with 20 RBIs, and seven extra-base hits. The shortened season cost him a chance to become the Razorbacks’ career leader in several categories.

While he missed a chance at an epic year, the rebuilding Orioles chose Kjerstad second overall in the 2020 MLB Draft and fixed him up with about a five-million-dollar start in life. In Arkansas, we were sure Baltimore got a good deal. He was a “sure thing,” until he wasn’t. Becoming an overnight news story in the “show” took four years.

First, there was a year-long battle to recover from Covid-related myocarditis, and an extended private baseball recovery at the Orioles’ training facility. After finally getting the okay to start “baseball-related activity,” he spent most of two years in the Baltimore minor league system, before a late-season callup in 2023.

He started 2024 back in AAA at Norfolk where he overmatched the league. Surrounding an unsuccessful three-week call-up to the Orioles in late April, he hit 16 home runs and drove in 58 runs in 56 games in AAA.

Since his return to the Orioles on June 24, he is hitting .438, with two home runs, two doubles, and eight RBIs. One of his homers was a grand slam in a 6—5 win over the defending World Series Champion Texas Rangers on June 29 at Camden Yards.

On a team filled with young prospects, Kjerstad looks like he might be in Baltimore to stay.

Lost Stories of the First Decade of the 20th Century

Fourth of July Leagues

Little Rock, Arkansas, had tried minor league baseball a few times before the turn of the 20th century with consistently bad results. The Little Rock franchise was not unlike most of the minor league cities during a time when the idea of pro baseball sounded exciting, but typically the leadership had math problems.

With ticket prices at about 25 cents for general admission, it took a lot of quarters to make payroll. Travel to league cities was mostly by train and players needed rooms, food, and equipment. It took some trial and error to realize the math didn’t work.

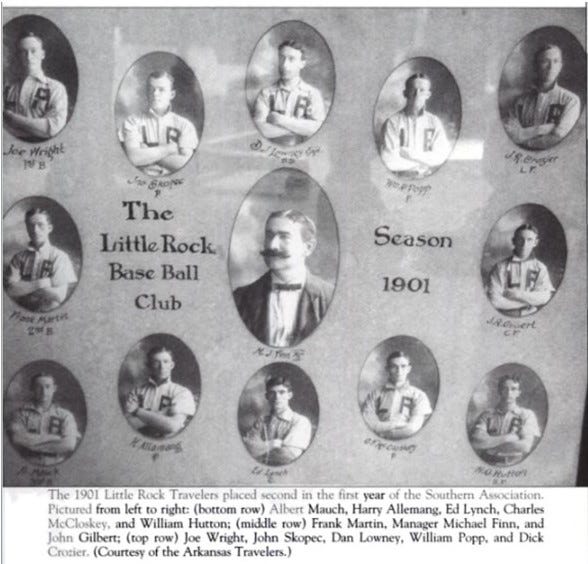

Some anonymous sports writer labeled these poorly planned dysfunctional collections of teams, “Fourth of July Leagues,” based on the tendency for minor leagues to cease operations by Independence Day. In the late 1800s, Little Rock had tried to make it work with minimal success, as Giants, Senators, Rose Buds, and Travelers. Things got better when the “new” Little Rock Travelers debuted in 1901, but the hard times were not over.

The Lost Story of the Unusual Mr. Finn

After several false starts in failing leagues, the baseball folks in charge of minor league baseball in Little Rock sent for a guy with a background in circus promotion and dog racing. Why not, they had little to lose, and he was certainly an attention-getter. The club needed a little attention.

On January 5, 1901, the Arkansas Gazette topped page three with the enigmatic headline, “Mr. Finn Is Coming.” The newspaper predicted, in the column below the mysterious headline, that this Finn gentleman was arriving from Ohio on Tuesday and would likely become the manager of the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association.

Michael J. Finn did have an impressive resume in boxing, sprinting, dog track promotion, and a traveling circus. He had “experience” in baseball and he liked it. In four seasons leading a pro baseball team, Little Rock’s new field boss had won a pennant, managed teams that folded in mid-season, and been jailed for playing on Sunday.

His last experience was a dismal season that ended with a court date for a "Blue Law" violation and a finish deep in the standings. His 1900 Marion Glass Blowers staggered to the conclusion of the Interstate League a woeful 47 games out of first place.

Although local newspapers reported the pre-selected manager was coming in from Ohio, Mike Finn was the son of Irish immigrants from Natick, Massachusetts. He was a few weeks short of his fortieth birthday; a deeply religious fellow, with a round midsection, and a prominent handlebar mustache. One biographer described him as likable, excitable, and sometimes gruff.

In the early days of 1901, Mickey Finn had done a lot of preparation for his new challenge. Finally, on January 14, he made his first trip to the city that would become his adopted hometown. The next day Finn would meet with the board and officially become the manager of the Little Rock Travelers. The Travs new field boss promised to release the names of his players soon. The curious fellow the press called “Mickey Finn” would prove to be an excellent choice for the fragile Little Rock professional baseball situation.

Mickey Finn’s new team was immediately competitive and the odd fellow from New England soon became the toast of the town. Baseball men often proclaim the success of a team depends on strength “up the middle.” Finn seemed to operate under that axiom. Among his first recruits were a catcher, a reliable pitcher, a seasoned second baseman, and a good defensive centerfielder.

Finn had managed perennial .300 hitter Jack “Jackrabbit” Gilbert in the Interstate League the previous two seasons. In one of his first moves, the aspiring Travelers manager convinced the speedy centerfielder to join his new team in the south. The former major leaguer was a good start. He would be the centerpiece for Finn’s new collection of players. Subsequently, the Cleveland Blues were having trouble signing second baseman Frank Martin, so Finn took advantage of the uncertain situation to sell the young infielder on a sure thing in Arkansas.

Finn did not look far to find an ace pitcher and a catcher. Ed Lynch, the catcher on his 1900 Marion team, would hit a team-leading .367 for the 1901 Travelers. Pitcher Harry Allemang, also recruited from his previous team in Ohio, would win 20 games and lose only four, the best winning percentage in the Southern Association.

Little Rock’s new team led the league for most of the season, and according to Travelers fans, finished the season in first place. As was common in the administration of the tenuous union that baseball leagues operated under in 1901, the new Southern Association was rife with controversy. Teams argued over make-up games, player contracts, and even the construction of baseballs. Little Rock claimed to have won the league on the field, but, unfortunately, the final result would be decided in a boardroom a month after the last game was played.

The Board of Directors of the Southern Association met in Chattanooga on October 20 for what would be a contentious debate that Little Rock papers called “The Chattanooga Farce.” Three disputed games would be awarded to Nashville, enough to make the Vols league champions by one game. Despite the bitter end to a successful season, Mike Finn was a local hero. The Travelers had won the pennant on the field and, amazingly, had turned a profit.

In his second season, Finn’s Travelers finished second in the Southern Association. The nucleus of his first team returned, and twelve games into the season, he added future major leaguer Jim Delahanty of the legendary Delahanty baseball family. Jim was 23 years old. He had opened the season with the National League New York Giants without much success, but he found his hitting stroke in Little Rock. Jim Delahanty would spend two summers in Arkansas and later play 1,169 major league games after leaving Little Rock. Four of his brothers would also play in the big leagues.

Allemang got help on the mound in 1902 from career minor leaguer George “Cy” Watt and another Ohio find, Whitey Guise. All three of the Travs’ dependable hurlers pitched 250+ innings and won 19 games. Delahanty hit a team-high of .328.

With basically the same regulars, the 1903 Travelers finished second again, despite concluding their season tied for first place. In a perplexing scheduling quirk consistent with the haphazard administration of minor league baseball in the early 1900s, Memphis had one more game to play. The Egyptians won their concluding game to finish the season one game ahead of Finns’ Travelers. After the usual post-season wrangling over disputed games, Memphis was declared the 1903 champion

Although he had won the hearts of Little Rock fans, Mickey Finn was a restless fellow. By 1904, with things not going as well as in previous years. It became a forgone conclusion that Finn was exploring the baseball job market. He probably should have taken one. With the team Mike Finn brought to Little Rock scattered around pro baseball, the 1904 Travs tumbled into the second division, and the fans were ready for a change.

Finn headed off to manage in Nashville in 1905 and the Travelers hit rock bottom, finishing last in both 1905 and 1906. Finn looked much better after those two disastrous seasons. So much better that he was coaxed back in 1907.

Probably without much thought or sincerity, Finn boasted that if the 1907 team did not return to at least a .500 season he would forfeit his salary. Thankfully the Travs finished 66—66 to save Mike Finn from his thoughtless boast.

In 1908, despite having the best player in the league and perhaps the most outstanding player in the history of the Little Rock franchise, the Travelers dropped back to seventh in an eight-team league. The story of Tris Speaker’s summer in Little Rock is one of the most interesting tales in franchise history.

By 1909 things were so bad that the Little Rock baseball ownership sold the franchise, players, and equipment in what amounted to a going-out-of-business sale. Mickey Finn moved on but kept his winter home in Little Rock.

Finn had managed the Travelers for seven of the first nine years of the franchise. He had led both competitive first-division clubs and hapless losers, and he was consistently an interesting story. The unusual fellow, Sportswriters loved to call “By T’under Mike,” remained in baseball until his sudden death in 1922. Throughout his life, he made Little Rock, Arkansas his off-season home.

The Lost Story of Tris Speaker’s Summer in Little Rock

In his best-seller The Baseball 100, Joe Posnanski ranks Tris Speaker as the 18th-best player in baseball history. Since such a ranking is mostly opinion,

I am going with Joe. Speaker’s place on the Posnanski list suggests he is also the most outstanding player ever to wear a Traveler’s uniform.

On March 17, 1908, Little Rock Travelers’ fans and local sportswriters were getting their first look at the cowboy from Texas who would be their center fielder for the upcoming summer. Tris Speaker made an impression in that first exhibition game against the major league Red Sox, but it would take the perspective of a Hall-of-Fame career for local fans to realize the preview of greatness they would witness during the six months Speaker spent in Arkansas.

Speaker stood nicely to address the ball and when he spoke it was with a loud noise. Jimmy Barrett recognized the crescendo tone resounding from the impact of bat and ball. Turning he ran toward the fence, but the sphere sailed gracefully overhead and bounded to the nearest friendly panel. Meanwhile, Speaker, conscious of the power behind that swing, sped to first, then to second, and was at third when Barrett heaved homeward. Charley Wagner intercepted the throw as Tris tripped down the last quarter toward home. He hurled straight at the waiting Carrigan, and by an eyelash, a legitimate home run was burned to a crisp nothing . . . but Mr. Speaker had made his mark.

Arkansas Gazette 3-18-1908

So how did this happen? How did a cowboy from North Texas end up playing in Little Rock and why was he not promoted during his epic summer?

In late February of 1908, newspapers announced, somewhat erroneously, that Boston had sold Speaker to Little Rock. In reality, Boston was not seriously interested in the young cowboy they had auditioned the previous fall. A chance in Little Rock was the best lead Speaker had for a baseball job in the late winter of 1908, and Boston was prepared to offer the Travelers a deal that would benefit both parties.

Speaker would spend March in a Little Rock uniform sharing West End Park with his former club. Some sort of behind-the-scenes handshake apparently included leaving the young outfielder with the Travelers as partial payment for the Red Sox use of the Travs’ home field for spring training. Fortunately for the major league club, the agreement also contained an option for Boston to reclaim Speaker for $500 after a season with the Travelers.

The details of the “deal” that resulted in Tris Speaker spending most of the 1908 season in Little Rock differ significantly depending on the perspective of the source. The Red Sox side of the agreement boasts that, after a season of needed improvement, they were able to claim a future Hall of Famer for $500. The Travelers leadership’s side of the story features vague details of a shrewd business deal that allowed one of baseball’s all-time greats to play 127 games in Little Rock, Arkansas, in exchange for sharing West End Park with Boston.

The bottom line is that Speaker spent the entire summer playing center field for the Little Rock Travelers in the Southern Association. He led the league in batting average. His .350 mark was 36 points better than the league’s second-highest average. Speaker also led the league’s hitters in hits, runs, and extra-base hits.

Speaker's redefined center field strategy of playing about 50 feet behind second base, resulted in league-leading totals for outfield assists, putouts, and double plays. Despite having a player who dominated the league in both offensive and defensive categories, the Travelers managed to finish seventh in an eight-team league.

Speaker played his last official game as a Traveler on September 3 against the Atlanta Crackers in Little Rock. He finished his historic season in his typical style, collecting three hits in four plate appearances in a 3–2 win. The next day, Speaker had two hits when the unofficial game was called in the fifth inning due to a rainstorm. In a related paragraph deep in the sports page, the Arkansas Gazette mentioned that after the rain-shortened game, Speaker caught a bus for the major leagues. “The Southern Association will be pulling for him.”

Arkansas Gazette 1908

Inevitably all outfield stars will be compared to Speaker and inevitably all will suffer.

Joe Williams, Cleveland Press

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/