Backroads and Ballplayers #56

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

This Is Baseball

“[Baseball] breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart….You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when you need it most, it stops.” Taken from a quote by A. Bartlett Giamatti

When you reach my age, you have two kinds of baseball memories, the fresh ones of seasons just passed and hard-to-take losses (For almost every team, all seasons end with a loss).

We also have cherished memories of what the game meant to us as kids:

Did you have a morning ball? At White Oak Grade School, when our “good” ball lost its cover we wrapped it tightly in electrical tape. It became our “morning ball.” The morning ball was often better than our good ball, and in the 15-minute games before the morning bell, it served us well in the wet grass.

Do you remember how your glove smelled? There was this stuff you bought in a shoe shop called Neets Foot Oil. You rubbed it into your five-dollar glove for hours, because some big league star on the back of a magazine said it was the thing to do. At least my glove smelled like a real baseball glove.

Did you ever invent a game for five players? If that is all you had in the neighborhood you had to. Over the barbed wire fence was an out. Out in the road, was a ground-rule double, and if you were on base when it was your turn to bat, a ghost runner took your place. In a typical five-kid game, the score might be 19 to 16, to 14, to 13, to 3. All skill levels and all ages were needed to make the game work.

Growing up in the Ozarks, I had planned to be the second baseman for the Yankees. I had to amend that when it took so long for me to be the second baseman for my summer team.

Hard Times:

The Razorbacks’ season ended on a low note. Am I the only one who thought they looked physically tired? Like most college teams the Hogs face a major rebuild, but nothing changes the banner that proclaims the 2024 team as the last SEC West Divison Champs.

Good News:

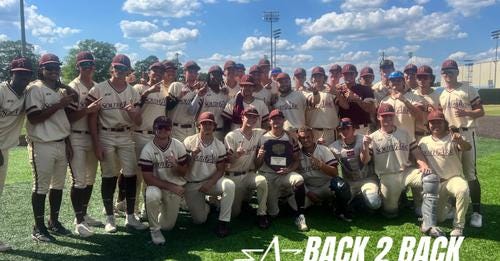

My friends following the South Arkansas Stars saw their team win two games in the Junior College World Series. Congratulations!

I understand that Jordan Wicks’ rehab is going well.

Gavin Stone has not allowed a run in his last two starts.

Grant Koch is a major leaguer. Koch was probably called up to replace a couple of injured-list guys. He needs to get his first big-league hit soon.

“Rube” and “Babe” in Boston

How about a lost story about a guy named George Foster? No, not that George Foster. George Arthur Foster was a superstar for Cincinnati in the “Big Red Machine” days. That George Foster was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003. This lost story is about “Rube” Foster.

Rube Foster is also a prominent name in baseball lore, but this obscure piece of Arkansas baseball history is not about the “Rube” Foster who was instrumental in the birth of the Negro Leagues? His story is well known. That was Andrew “Rube” Foster, a famous player/manager/executive from the Negro League days. The Baseball Hall of Fame described him as the “Father of Black Baseball.” He was inducted in 1981.

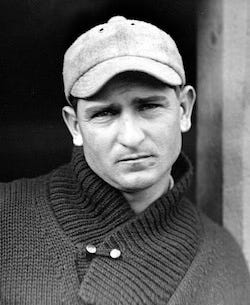

The biographies of the Fosters mentioned above will never make a “lost story” list.” The pitcher who shares names with the HOF Fosters was a World Series hero and the pride of Bonanza, Arkansas. Despite a very good major league pitching record and World Series stardom, George “Rube” Foster’s story is buried in the shadows of Arkansas baseball history.

Bonanza, Arkansas, earned its name in the late 1880s when coal was discovered in South Sebastian County a few miles from the Oklahoma line. By the end of the first decade of the 20th century, the sleepy rural community had become a town with a population near 1,000. Bonanza had a railroad station, boarding houses, a company store, and a baseball team. For the next 50 years, the Bonanza Blues would be among the elite town teams in Western Arkansas.

Arkansas’ adopted son George Foster was born in Lehigh, Oklahoma, in 1888. His family arrived in Bonanza about the turn of the century where young George found his place in the coal mines and as a pitcher for the Bonanza town team. Although he was on the small side, Foster was an outstanding Sunday afternoon pitcher.

Although he was good enough in his 20s to play in the minor leagues with various teams in Oklahoma, Foster seemed to be going nowhere in the Western Association until the St. Louis Browns bought his contract in June 1911.

The Browns sold him to Houston in the Texas League later in the year and after a 24-7 breakout year in 1912, George Foster got a new nickname and a major league promotion. This George Foster of Bonanza, Arkansas, can be found in BaseballReference.com, under his baseball name, “Rube” Foster.

After a three-win, three-loss, rookie season in 1913, Rube Foster became a pitching star for a Red Sox team that would finish second in the American League in 1914 before winning two consecutive pennants and two World Series in 1915 and 1916.

He had a good year in 1914, starting the year with four complete-game shutouts in May before a knee injury in late June sidelined him for most of July. He finished 14-8, with an excellent 1.70 ERA.

In 1915 Rube Foster was joined in the starting rotation by a lefty named George Ruth. Foster led the team in wins, innings pitched, complete games, and shutouts. The Boston Globe proclaimed on May 4, after a 2-0 shutout over the Washington Senators, “Walter Johnson Met His Match.” Ruth posted 18 pitching wins and led the team in home runs with four, in only 92 at-bats. Boston never seemed to do the math.

Foster was the star of the 1915 World Series winning two complete-game decisions. In Game Two, Foster went three for four at the plate, drove in the go-ahead run in the ninth inning, and held the Phillies to three hits in the 2-1 win. He was also the winning pitcher in the deciding fifth game. Rube Foster was a World Series hero, and the lead story in Arkansas newspapers.

In the Red Sox’ second pennant-winning season in 1916, Foster got off to a shaky start before pitching a no-hitter against the Yankees on June 21. From mid-July until the season’s end, he won 9 straight decisions, but with a pitching staff that included Babe Ruth, Dutch Leonard, and Carl Mays, Foster was not part of the Red Sox long-range plans. The hero of the previous World Series, Foster’s only series appearance was three scoreless relief innings in the Game Three loss to the Brooklyn Robins. Boston won their second consecutive World Series title in five games.

In 1917, on a pitching staff that included Babe Ruth, Dutch Leonard, and Carl Mays, Foster became a spot starter. In 19 starts and 14 relief appearances, he posted a 14-7 record. His respectable 3.06 ERA was the highest among the starting pitchers. On a pitching-heavy team, Foster was the oldest starting pitcher on the Red Sox staff and after an even less significant role in 1917, Foster was traded to Cincinnati in the off-season. Despite the need for players due to the significant number of major leaguers in military service, the Reds could never come to terms with Foster. Rube Foster’s big league career was over.

For the next few summers, Foster’s name would occasionally appear in local newspapers in the lineup for a town-team in the Fort Smith area, but usually as an infielder. He could apparently still hit well enough that five seasons after his last major league game he was playing second base for Henryetta in the Western Association and leading the team in batting average.

He tried pitching again for Oakland in the Pacific Coast League in 1924 and 1925. After two lackluster seasons in the PCL, Foster found some minor league work in the Southwest before making his retirement home in Fort Smith.

The World Series hero with the familiar name had a career record of 58 wins and 33 losses with a sparkling 2.36 ERA. He pitched a major league no-hitter and 15 complete-game shutouts. He was on two World Series Championship teams, played with Babe Ruth, and was the most famous Arkansas pitcher in the first twenty years of the 1900s. Unfortunately, his story is one of the most puzzling lost stories of Arkansas baseball history.

Another Rube and Another Babe Ruth Story

Rube Foster had the most successful big league pitching career for an Arkansas resident in the early 1900s. ( Foster was born in Oklahoma, but lived most of his life in Sebastian County) Although his career was brief, Foster won 58 games on baseball’s biggest stage, including a masterful performance in the World Series.

Rube Foster made national headlines, but there is another story about a county boy from Arkansas called Rube who won 319 professional pitching victories during the same period. Unlike Rube Foster’s somewhat obscure accomplishments, Rube Robinson’s career is among the most celebrated stories in Arkansas baseball history.

Rube Robinson was born John Henry Roberson in Floyd, Arkansas, about 1887. His actual birthdate is somewhat debatable. Early in his career, careless sports writers began identifying the dominating left-handed pitcher as Rube Robinson. His major league record at BaseballReference.com lists his stats as Hank Robinson, and he was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame as John Henry Roberson. If that is not complicated enough, dozens of his pitching wins are missing from his records.

A key factor in his shrewd homespun free agency policy was his preference to play for the Little Rock Travelers. One of my favorite stories about his aversion to big-city life is an account of his last stint in the big leagues. Nothing in Rube Robinson’s life reveals his disdain for baseball in the majors as perfectly as his encounter with Babe Ruth.

Initially, Robinson had pretty good experience in major league baseball. He pitched in five games in 1911 and two complete seasons in 1912 and 1913 with the Pittsburgh Pirates. He won 26 games for the Pirates, became friends with Honus Wagner, and he was adapting to the idea of big-city baseball.

As content as he seemed in Pittsburgh, he was equally unhappy after a trade to the Cardinals. Forced into a relief role between starts he developed irritating arm problems exacerbated by an off-the-field conflict with the Cardinals’ manager, Miller Huggins.

After two lackluster years in St. Louis, the Cards optioned their sore-armed lefty to San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League for the 1916 season. In a move typical of his shrewd free agency policy, Rube Robinson refused to go. He declared he would pitch in Little Rock or for the Floyd town team. He meant it, and the Cards knew it. By the end of 1916, St. Louis had relented, and he was 11-1 pitching for the Little Rock Travelers.

Life was good. The Travs had the benefit of a pitcher with big-league skills, Rube was happy to be back in Arkansas, and things were looking up for the newly refurbished Travelers team. That all changed in 1918.

The Travs were much improved in 1918, but with World War I raging overseas and the player supply dwindling, the Southern Association called off the season on June 30. Robinson was 8-2 when the league folded. Sunday afternoon baseball in towns like Floyd, Arkansas, was no longer an option, so if Rube wanted a job, he would have to tolerate life in the major leagues.

Despite their rocky past, Yankee manager Miller Huggins persuaded Robinson to join the New York Yankees for the remainder of the season. At least, that is what the contract indicated. Huggins obviously should have known better.

Robinson once again proved that he was a big-league pitcher. He had appeared in 10 games for the Yanks and pitched 39 innings, mostly in relief, when on August 12th he got a start against the Red Sox.

On a Monday in Boston, with a war raging in Europe, the Red Sox drew only 2,800 to an afternoon game at Fenway Park. Boston was hanging on to first place by a single game and had lost three of their previous four games. That day at Fenway, Boston went with a lefty of their own, a 23-year-old named George Ruth. Ruth pitched well, allowing the Yankees only two runs on four hits. Rube Robinson was better. He held Boston to one run on three hits, and the Yanks prevailed 2-1. Robinson would retrospectively recall the game as a highlight of his career.

In typical Rube Robinson tradition, after outpitching Babe Ruth, he picked up his mid-month check and returned to Floyd, Arkansas. Twenty games remained in the Yankees’ season, but Rube Robinson was ready to be John Henry Roberson again. It would be his last major league game.

Except for a brief loan to the New Orleans Pelicans for a playoff series and a few games for Atlanta at the end of his career, Rube Robinson remained the ace pitcher for the Little Rock Travelers.

Robinson was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1962 as John Henry Roberson and the Texas League Hall of Fame in 2011 as Rube Robinson.

“Rube Robinson didn’t flunk out of the major leagues, he simply put in for a transfer.” Jim Bailey Arkansas Democrat

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

I think leather tastes a LOT better than that.

Ghost runners were a necessity. But you really hit the memory button on the smell of the glove. And for me, the taste - I always had a habit of chewing those loose laces while playing right field. I can taste it now.