Backroads and Ballplayers #55 - The Hogs Start Over, Lost Stories: Grandpa and the Deans, An Adventure in Bastrop.

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Omahahogs? - Grandpa Stories: Deans in Dardanelle and an Adventure in Bastrop

The Hogs Start Over

The 2024 version of the Hogs was number one in the RPI for much of the season and never ranked lower than five in the polls. That looks pretty good in print, but the high point came in March, and the low point in late May. The downhill trend has us concerned, but a slump in the last half of the season is not an unusual rollercoaster ride through the excruciating gauntlet of the SEC and the ho-hum week spent playing in the SEC Tournament.

Concerns:

In games that Hagen Smith did not pitch, over the last five SEC series and one SEC Tournament game :

The Hogs were outscored 81 - 59.

Opponents scored less than five runs one time. (A&M)

Their record in those games was 4 - 7.

Miraculously, counting the games Smith started, they went 8 - 7 over the last half of the conference schedule and won the West.

History:

Good memories are still easy to recall.

The 2022 Razorbacks were also struggling when they went 0-2 at the SEC Tournament, then won a regional at Oklahoma State and a Super Regional at North Carolina before making the College World Series semifinals in Omaha. The last four national champions have all come from the SEC, and only Vanderbilt in 2019 reached the semifinals of the SEC Tournament.

When the dust settles on the 2024 Razorbacks baseball season, one of the first questions has to be, “Would this have been a (disappointing) (acceptable) (good) (very good) (excellent) season if evaluated from a February perspective? We will vote later.

I am a steadfast Dave Van Horn fan, worried but optimistic.

Town Teams Part III

Grandpa Stories

Our ancestors had never seen Dizzy and Paul in person, but most knew someone who had… —From Hard Times and Hardball

In my travels, I hear a lot of “grandpa stories.” I love them, and I am careful not to dispute any of them. Many of these handed-down tales are about Dizzy and Paul Dean.

“My grandpa played against the Deans.”

“My grandpa knew Dizzy Dean personally.”

“My grandpa walked to Lucas to play against the Deans.”

Or my favorite, “My grandma may have dated Dizzy Dean.”

Certainly the most common of these grandpa stories are recollections that include a game the ancestor played against a town team that had Dizzy and Paul Dean. Those stories that have Lucas as a location are the most questionable. By the 1920 census, the Deans had moved from Logan County to Chickalah in Yell County. Dizzy was 10 and Paul was eight in 1920. It is unlikely that they played any town team games in Lucas unless they played there when they were living elsewhere.

That leaves five years on Chickalah Mountain before the Deans moved to Spaulding, Oklahoma, in 1925. Once again, Diz was about 15 years old and Paul was 13 or so when they left Yell County. Their father, Abner, was a prominent member of local community teams, but it seems a little unlikely that Dizzy and Paul played town team games before the age of 14 and 12 respectively.

So, are all the grandpa stories about Dizzy and Paul fiction? Maybe not. Dating Diz, is unlikely, but dating Paul? After the 1934 World Series, Paul seemed intent on finding a wife. He approached several prospective brides before settling on a former Miss Russellville just before Christmas. It turned out to be his biggest win. Link to Paul Dean Weds Miss Russellville

AND…there seems to be solid evidence that Dizzy and Paul did play on local teams, but most of those games occurred several years after their adolescent years in Chickalah.

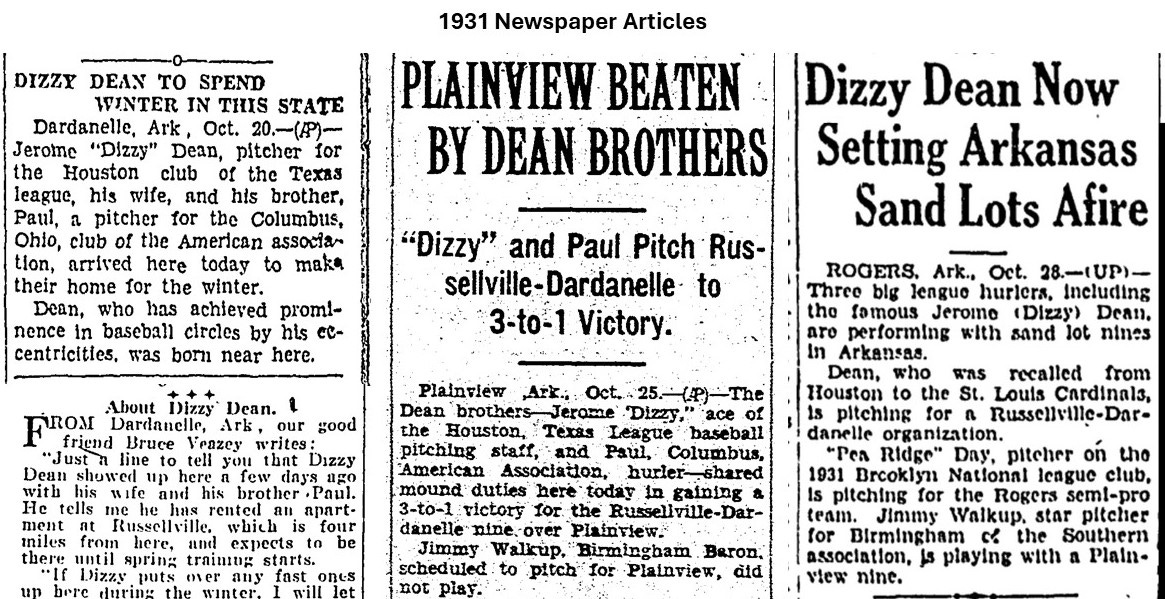

In 1930 a 20-year-old Diz won his only start for the Cardinals, giving up one run in a complete-game victory. Perhaps to teach the somewhat difficult-to-manage Diz a lesson, the Cardinals sent him down to their farm club in Houston for the entire 1931 season. There, he racked up 303 strikeouts and recorded 26-10 record in more than 300 innings of work. He was chosen as the league MVP and pitched the Buffs to the Dixie World Series.

Despite reservations about Dean’s attitude, St. Louis would be forced to promote their rambunctious county boy to the big league roster in 1932. In the meantime, Dizzy had a new wife, a minor league income, and an off-season business plan. Although his fame preceded his promotion, he was most famous in the Arkansas River Valley. How about a winter in a community where he was a local hero, and he could make extra cash pitching for some town teams?

Dizzy, along with younger brother Paul who was already a successful minor leaguer at age 18, apparently arrived at his winter home in late October. The traveling Dean group also included Diz’s new wife and father Abner. According to the Dardanelle Post Dispatch, Diz came by the newspaper office acting as his own press agent. He announced the family would be spending the winter in Dardanelle, Arkansas. Later, in true Dizzy Dean style, he announced that he had rented an apartment in Russellville.

Although fall baseball in Arkansas is a weather risk, indications are that the Deans played well into November throughout Arkansas and Southern Missouri. One newspaper report indicates the appearance fee for a “Dean Brothers” game was $150. Diz’s new wife, Pat, was a clever business manager and although the first winter in the River Valley was a modest beginning, fall barnstorming would be part of the Dean’s business model for years to come.

It is almost impossible to know how many games the Deans played that October and November. Where they played, and the names of teammates and opposing players might be found in the small-town newspapers of the day.

Perhaps your grandpa, uncle, cousin, or the old fellow down the street really did play with or against Dizzy and Daffy Dean. That handed-down family legend may be true!

Elmer

Another amazing Dean adventure took place that fall in the Arkansas River Valley. The oldest Dean brother, Elmer, was perhaps mentally challenged or some say he was just extremely impulsive and unrestrained. That is also possible given Diz’s tendency for reactionary episodes.

In a bizarre incident in 1928, Elmer became separated from the family in Houston, Texas. Despite Elmer’s erratic personality, Abner Dean felt sure that he would find his way back. He did eventually find his way back to the family, but it took three years.

When word got out in the Arkansas River Valley that the Dean family was spending the off-season in Dardanelle, a farm hand in Plumervile pointed to a photo in the local paper announcing, “That is my brother Jay.”

The brothers were contacted by a farmer in the neighboring county, and Diz and Paul decided to check it out. They found their long-lost brother working on the Stobaugh farm in Plumerville. They loaded up a somewhat reluctant Elmer and took him back to Dardanelle. He would remain with the Deans most of his life, working around the ballpark. His is a story of its own for a later time.

An Adventure in Bastrop!

Otis Brannan’s life is a collection of adventures. He was a town-team star in the earliest days of organized semi-pro baseball in Arkansas. In his early 20s, Brannan was a standout infielder at Arkansas Normal College (University of Central Arkansas). He played in more than 1300 professional games and eventually became a big-leaguer with the St. Louis Browns.

Along the way, he almost lost his life to a line drive during fielding practice, took an unscheduled mental health “retirement,” survived an earthquake and a life-threatening auto accident, and played town team baseball in a Ku Klux Klan war.

And…he also played with Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Otis Owen Brannan was born in 1899 near Greenbrier, Arkansas, a seemingly unlikely place to be discovered as a major league baseball prospect. Despite the rural location, Brannan was in the right place at the right time. As he reached his late teens in Greenbrier, the little community was becoming the center of amateur baseball in Arkansas.

Dr. Earl Williams arrived in Greenbrier around 1908, and his passion for baseball resulted in a well-organized semi-pro league and an outstanding town team. The Greenbrier semi-pro team dominated the Faulkner County League and successfully challenged prominent teams from other areas of the state. Much of the success of Williams’ local team was due to an outstanding teenage infielder named Otis Brannan.

By the early 1920s, Brannan was playing his springs for Arkansas State Normal School, (later renamed the University of Central Arkansas) and his summers for the Greenbrier town team. After his final season at Arkansas Normal in 1922, Brannan accepted an offer to join a top regional semi-pro team and headed south for an encounter with some of baseball history’s most notorious characters.

Wiley “Dinty” Montgomery, a semi-pro teammate of Brannan, had connections in Northeast Louisiana. By mid-June, Brannan and Montgomery were playing with a prestigious semi-pro team in Bastrop, Louisiana. Bastrop was a small hamlet in Morehouse Parish that was regularly in the headlines for two unrelated newsworthy events, outstanding semi-pro baseball and Ku Klux Klan violence.

Twenty-three-year-old Otis Brannan was an attention-getting local star in Bastrop during the socially tumultuous summer of 1922. The Bastrop semi-pro team was owned by a local banker and a KKK-approved sheriff. At times, the violence and the baseball became inexorably connected. On August 24, Brannan’s semi-pro team played a game at a county-wide picnic designed to unify a divided community. After the game, the Klan blocked the road, kidnapped two prominent Klan opponents, and later murdered the men.

While Bastrop was in national headlines daily describing the bloody social violence, the local papers extolled a dominant semi-pro baseball team. Brannan, spelled “Brannon” in most newspaper accounts, was the regular second baseman and hit .350 for a team loaded with Arkansas country boys.

In September, the Monroe News Star ran an article listing the winter plans of the Bastrop semi-pros. Many of the departing players were heading home to rural Arkansas. Third baseman Davis was headed back to Strong, Arkansas; Neighbors, a regular pitcher, was going home to Arkadelphia; and his catcher, Wiggers, was bound for his hometown of Eudora. Starting outfielder, Zilkey of El Dorado had a short trip home to Union County, Arkansas. Yell County native “Dinty” Montgomery had secured a position as principal of a local high school, and star infielder Otis Brannon would winter at his home in Greenbrier.

Back in Bastrop in 1924, a town that immodestly billed itself as “The Home of Better Baseball,” Brannan found himself part of a national sports story, but not the kind that centered on home runs or great pitching performances, but on a notorious scandal.

On August 3, 1921 baseball’s powerful commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, had suspended eight members of the Chicago White Sox for life. The Sox had suspiciously lost the World Series, and although they were acquitted in court of conspiring with gamblers to fix the World Series, Landis exercised the immense power of his position to end the accused players’ careers.

In what would become known as the “Black Sox Scandal,” the eight players, including the hero of the American South, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and the Sox ace pitcher, Eddie Cicotte, were doomed to a lifetime away from the sport that made them famous. The eight scattered into the backroads and shadows of American baseball, including an obscure town in Northeast Louisiana.

Richard Bak, a Detroit writer, and authority on the Black Sox Scandal, explained the pitiable fate of the disgraced players in his blog for the Detroit Athletic Company.

In the summer of 1923, a baseball team from Bastrop, Louisiana, was tearing up sandlots and cow pastures in every direction. The semipro nine featured a round little pitcher named Moore, who dazzled batters with a virtually untouchable assortment of junk pitches, and an outfielder named Johnson, whose slugging and fielding prowess never failed to astonish. “The team has been cleaning up in Morehouse Parish,” marveled a local newspaper, “and has walloped almost every club it has met in north Louisiana and south Arkansas.”

Before too long, the identities of the team’s stars were revealed. “Johnson” actually was “Shoeless Joe” Jackson, an illiterate country boy generally considered the greatest natural hitter the game has ever seen. “Moore” was Eddie Cicotte, a lifelong Detroiter widely admired as one of the “brainiest” pitchers around.”

Jackson played about 30 games in Bastrop in June and July of 1923 as “Joe Johnson.” Cicotte played a few more weeks. Rumors that other Black Sox stars played a game or two are unsubstantiated. Brannan remained all season and continued to shine for Bastrop. His brush with history and the notorious Black Sox remain obscure footnotes in a sordid tale of American baseball.

In the spring of 1924, Ray Winder, a legendary Arkansas baseball executive, who operated several minor league franchises in Oklahoma, picked up Brannan from Shreveport. Winder dispatched the young infielder to his Muskogee Athletics club in the Western Association and then dropped him down to Class D Ardmore to begin the 1924 season and a 1300-game pro career.

Brannan remained in pro baseball until 1941. In his after-baseball life, he traveled extensively as a pipe fitter before eventually returning to the family farm in Greenbrier. Otis Brannan died in Faulkner County in 1967.

More of Otis Brannan’s story in Backroads and Ballplayers p. 44

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

A personal message:

Happy Memorial Day and Thanks,

While I do appreciate the positive feedback for these weekly posts, please temper your compliments with the fact that I love this work.

Philip Martin’s column in the ADG this week reminded me how much I enjoyed getting the Sporting News in my mailbox each Monday. I want to put something in your email (or share on Facebook) that maybe you can’t find anywhere else.

While I hope you enjoy the Arkansas baseball history I send to your mailbox each week, please remember that my motivation is really quite selfish. I love sharing these old stories, and it keeps me out of trouble!

ALWAYS FREE - As of today, Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly had 465 readers last week. THANKS AGAIN.

If you particularly like a post, you might click the “like” button….

Jim