Backroads and Ballplayers #51

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Back to Johnson County and Arkansas Love of the St. Louis Cardinals

The Baseball History of Johnson County

I am heading to Clarksville this week to speak to the Johnson County Historical Society. (Thursday, May 2, 7:00 PM 131 W Main St.)

I have been looking forward to seeing the work they have done on their downtown museum and sharing some fascinating stories about Johnson County baseball history. There seems to be no end to the rich history of the game in that part of the state.

Mark Weatherton, a friend of mine who is almost always correct, did some thorough research a few years ago about the birthplace of Arkansas major leaguers. Mark determined that Johnson County was one of only ten Arkansas counties that had not produced a big-league baseball player. Although some believe the legendary Boss Schmidt and his brother Walter were born in Coal Hill, most sources agree with Mark.

That certainly does not mean that quality baseball wasn’t being played in Johnson County. On the contrary, an argument could be made that the coal mining region of Western Arkansas was the center of competitive town-team baseball in Arkansas in the early 20th century.

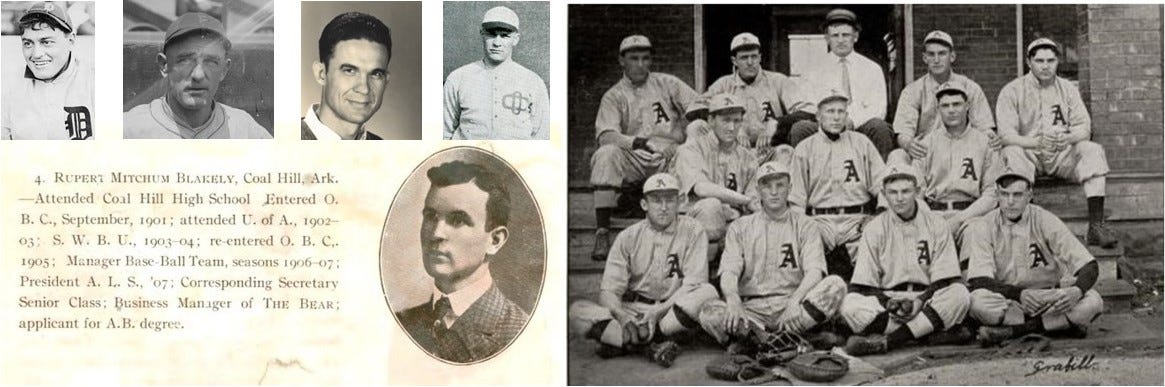

Cowan was dug up by Riggs three years ago from Johnson County along with Coyle, and Blakely. Johnson County is the home of Charlie “Boss” Schmidt, of Detroit and Walter Schmidt claimed by Cleveland. Rupert Blakely goes to Brooklyn, and now this boy Cowan. Can any other state challenge Arkansas as the producer of talent out of one county? -Jonesboro Daily News, 1909

In the early days of professional baseball in Arkansas, young men leaving their traditional jobs for a baseball career fell into two categories—more privileged individuals who wanted to try an adventure in pro baseball and others who saw baseball as an escape from the hard life they had inherited. The Johnson County boys of the early 1900s represented both groups.

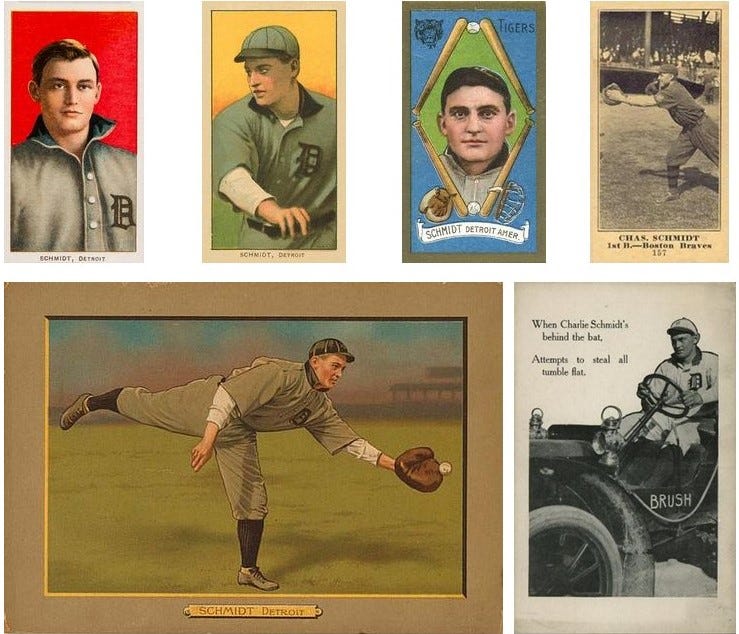

Charles “Boss” Schmidt had escaped the Johnson County mines in 1901, with a nickname earned in the coal mines and a reputation built as a tough-as-nails baseball player. His brother Walter followed in 1906 as a 20-year-old minor league catcher. The Schmidts were Arkansas’ first baseball stars. The sons of German immigrants, the brothers were born in Pope County, but the Schmidts called Coal Hill, Arkansas, home from an early age. For Boss and Walter, baseball was a way out of the mines and the backbreaking life down the dark perilous shafts.

On the other hand, three sets of brothers who became pro baseball stars were the sons of Johnson County doctors. Edgar Cowan, born in 1885, and his younger brother, Weaver, born in 1892, played more than 800 professional games each, including a year together in the Western Arkansas League in 1924. The Coyle brothers, Elmer and Norman, played college baseball and eight seasons each in the minor leagues. The Blakelys, born almost 20 years apart, were college baseball standouts and minor-league baseball stars. Dwight, the younger of the brothers, played minor league baseball for Clarksville in the 1924 Western Arkansas League and was inducted into the University of the Ozarks Hall of Fame in 1991. Rupert Blakely replaced Tris Speaker in center field for Little Rock in 1908 and is part of one of the most compelling “mysteries” in the baseball lore of his day.

At Clarksville this week, I am going to share dozens of stories about these and other men from Johnson County who played college and professional baseball in the days when baseball was “Arkansas’ Game.” Next week several of these “lost stories” will be posted in this weekly column.

Lost Story…Why Arkansans Love the St. Louis Cardinals

Are you going to be a farmer?”

“No ma’am, a baseball player.”

“For the Cardinals?”

“Of course.” – From A Painted House – By John Grisham

I received a transistor radio for Christmas in 1959. It was about hand-sized, had a leather case, and operated on a battery that I soon realized needed a backup ready for an emergency transplant. Some of my most vivid radio memories were of a loud, heavily-accented voice, proclaiming that I was listening to the “Cod Nal Baseball Network.” In the daytime, that network arrived in the Ozarks via KWHN in Fort Smith, and in the evening, from KMOX in St. Louis.

The distinctive voice on that broadcast was Harry Caray, one of the most iconic baseball broadcasters in American radio history. His partner was equally distinctive and celebrated Jack Buck. The Cardinals were not my chosen team, but they were the only game available on my radio in Ozark, Arkansas. I followed every game while claiming to be a Yankee fan. Like millions of my generation, I loved Mickey Mantle, but it seemed every adult I knew was a Cardinal fan.

What is it about the St. Louis Cardinals that unquestionably makes them the chosen team of a majority of Arkansans? Some of it is a historical and cultural confluence of several factors from the first half of the 20th century. Arkansas was basically a rural state for much of the early 1900s and baseball was part of the summer routine. Three acres, a ball, and a bat were all it took to play, and every community had a town team. Arkansans from this era grew up in hard times. They endured a world war, a pandemic, a historic flood, and a great depression. Baseball was an escape and they loved the game.

By the 1930s, new and exciting technology brought baseball into their homes. Radio took them to the stage of the Grand Ole Opry and to Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, places most would never see in person. They identified with the mountain music and they connected with the baseball team playing in St. Louis. Especially, since two of the most famous stars on those early 30’s Cardinal teams were Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean and Paul “Daffy” Dean, from Logan County, Arkansas. The Cardinals had won World Series Championships in 1926 and again in 1931, but the 1934 season would be the ultimate event in the romance between Arkansans and the St. Louis Cardinals.

Arkansas country boys were prominent from major league baseball’s beginnings, but at no time was this extraordinary success more evident than in 1934, when one of the nation’s most rural and least populated states produced some of major league baseball’s most celebrated stars. Dizzy Dean was voted the Most Valuable Player in the National League. Waldo, Arkansas’ Travis Jackson finished fourth, Paul Dean was ninth, Montgomery County’s Lon Warneke finished thirteenth in the voting, and Arky Vaughan from Madison County was twenty-third. Over in the American League, Schoolboy Rowe from El Dorado was fourth in MVP voting and Yankee catcher and White County native Bill Dickey batted .322 and was named to the American League All-Star Team.

The rowdy, impetuous, and talented 1934 version of the Cardinals was tagged with the nickname, “Gas House Gang.” Their accomplishments and rough-and-tumble ways endeared them to their 1930s fan base and secured their place in Cardinals’ history. They scrambled to the pennant on the last weekend of the season with the Deans winning the last three games. Our great-grandparents were listening, and Arkansas was indeed Cardinal Country.

The 1934 World Series between the Gas House Gang and the Detroit Tigers was billed as the matchup of Arkansas pitching stars, and the first three games played exactly on script, with Dizzy Dean, Schoolboy Rowe, and Paul Dean trading pitching victories. Unfortunately for Rowe, his win took 12 innings and 132 pitches to come to a 3–2 conclusion. He was never as sharp the rest of the series and the Cardinals prevailed in seven games, with Dizzy Dean pitching an 11-0 shutout in the finale. The Gas House Gang had finished the dream season and caught the imagination of baseball fans everywhere, perhaps nowhere more than in the home state of the Deans, and Schoolboy Rowe.

Few Arkansas fans saw the Gas House Gang in person, but they talked about them like they knew them personally. The games and their conversations about them helped Arkansans through some tough times. They never saw Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, but they imagined what it looked like. It was green and symmetrical, not unlike the converted cow pasture where they played on Sunday.

They had never seen Dizzy and Paul in person, although most knew someone who had. They knew Diz was tall and lanky, with a shock of unruly dark hair. His uniform didn’t fit quite right and he had a quick country grin. A lot of young men in their community looked like that.

In the 1940s, Cardinal fans, including those in Arkansas, fell in love with a line-drive-hitting first baseman named Stan Musial. Stan “The Man” played more than 3,000 games as a Cardinal and remains the most beloved Red Bird of all time. He helped Cardinal fans through a world war and teamed with a hard-nosed throwback named Enos “Country” Slaughter to win three World Series.

Some tried to copy Musial’s batting style, left-handed, in an awkward slouch, with his bat pointed straight up. They had seen it on the radio. Our grandpas told us about Musial’s heroics and Slaughter’s mad dash from first base to score the winning run in the 1946 World Series. After all, they were there, listening on the radio.

The 1960s radio generation did not have to see Lou Brock steal 888 bases as a Cardinal, the radio broadcast vividly described the Arkansas native disrupting the opposition with his speed. They heard Harry and Jack describe Bob Gibson’s intimidating presence, before finally getting to see him win two championships on TV. In 1967, local fans celebrated Stephens, Arkansas’ Dick Hughes’ amazing rookie season. Forced into the rotation by injury, Hughes went 16-6 and was instrumental in the championship season.

Regardless of Arkansas baseball fans’ allegiance to today’s St. Louis Cardinals, the Red Birds are culturally and historically the Arkansas team. They are the team of our great grandfathers, and the legacy of baseball tradition found deep in the roots of our rural past. The stories are fading and somewhat muddled in the retelling, the “lost stories of our grandpa’s game.”

“If you think Justin Verlander is tough you should have seen Bob Gibson!”

If you know someone who would enjoy this weekly column/blog, please share.

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/