Backroads and Ballplayers #50

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

The Bad, The Lost, and Down the Stretch in the SEC

How Bad are the White Sox?

Every morning I check the box scores of Arkansans in the major leagues. That doesn’t take long. Currently, there are only five, Jordan Wicks, Conway, Gavin Stone, Lake City, Jaylen Beeks, Prairie Grove, Drew Smyly, Little Rock, and Jacob Junis, Jacksonville.

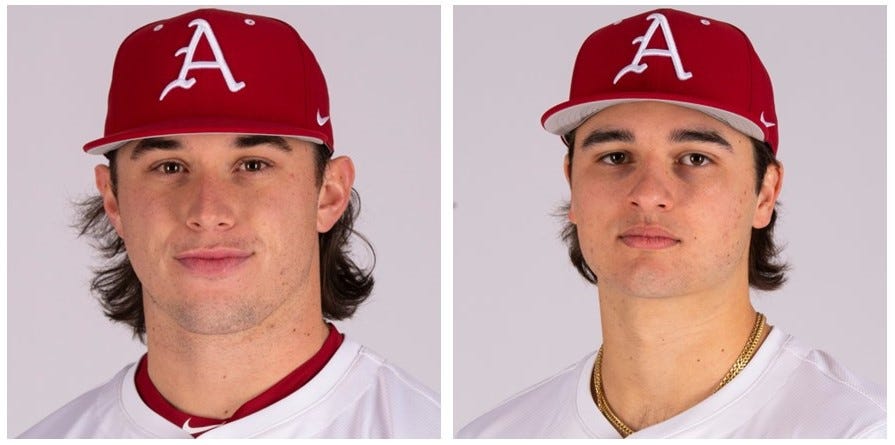

Once or twice a week, I check on the former Razorbacks, which leads me to the unfortunate story of the 1924 Chicago White Sox. Andrew Benintendi and Dominic Fletcher are currently incarcerated there and sentenced to serve hard time with the “Sad Sox.” Today, Monday, April 22, the 2024 edition of the Sox is certainly living up to the old 20th-century sports writer’s prophetic nickname, “Pale Hose.”

The Sox are 21 games into their schedule, with 3 wins and 18 losses. They are “winning” at a .143 clip, and have lost nine of their last ten. The Sox are last in MLB in runs scored, batting average, home runs, and OPS.

The pitching is not much better. They are 28th in ERA and home runs allowed and 29th in strikeouts. Incidentally, they are 26th in fielding percentage. It is hard to see where the White Sox can look to see something encouraging.

With little hope for improvement, they will likely fire someone, release some guys, and trade for some has-beens. And…go on to finish last in their division.

I love Benintendi and Fletcher. They are among my all-time favorite Razorbacks. Benintendi is hitting .158 with one extra-base hit. His on-base percentage is .200. He makes me sad. I am convinced his hand injuries have greatly diminished his skills. I hope I am wrong. He is my guy.

Dom’s batting average is .222. He has yet to hit a home run, and he has struck out 17 times and walked only four times. These are tough times for the White Sox and our guys need something good to happen soon.

Lost Stories: Encounters with the Babe

Walkup, James, “Jimmie” “Lefty”

I get a lot of emails. I love to know that there are others out there who appreciate the history of Arkansas baseball from the days when our state had an unusually prominent place in professional baseball. Many of your comments and questions are about the “lost stories.” Last week I received a note from a reader who was, “Amazed that I had found so many obscure stories.” From my perspective, I am sure that I will never run out of these forgotten tales.

This backlog of interesting biographies and intriguing adventures has moved most of my work from authoring books to trying to cover as many individual stories as possible. So, look for more “lost stories” in the weeks to come.

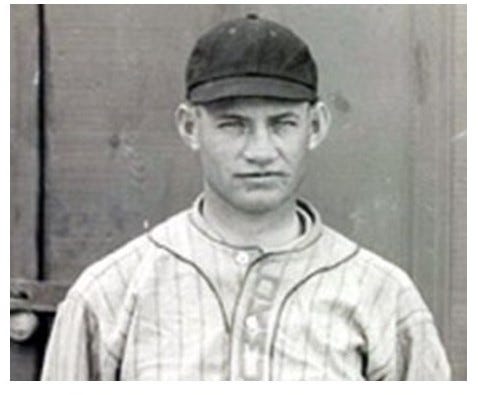

One of my favorite almost-forgotten individuals is a diminutive little lefthander whose life is filled with so many interesting adventures that it might take a book to record them all. Known as “Lefty” to baseball writers from his time, Jim Walkup was one of the outstanding pitchers in early Arkansas baseball history.

James Huey Walkup was born and grew up in tiny Havana, Arkansas, a little village in western Yell County, known today as the “Gateway to Mount Magazine State Park.” In addition to James Huey Walkup, the community would later produce two other major leaguers, the great Johnny Sain and Jim’s cousin James Elton “Jim” Walkup.

James Huey, known as Jimmy to his teammates and Lefty to sportswriters, was a star in the Western Association for seven seasons, before and after his service in World War I. During those pre-1920 years, he pitched for Muskogee, Oklahoma City, Joplin, and Okmulgee. He won more than 90 games in the WA before he was promoted to Fort Worth in the Texas League in 1924. At Fort Worth, he continued his success, winning a combined 41 games in 1925 and 1926. Walkup remained with the Fort Worth Panthers until 1930 except for his brief major league visit in 1927.

Fort Worth was on a run of great teams during the 1920s. Many of those teams are ranked among the best minor league teams of all time. Walkup would win more than 100 games in the Texas League, and he was perhaps the best control pitcher in league history. In more than 1,500 innings pitched, he walked just 276 batters, an average of 1.6 per nine innings.

The little lefty got hitters out with amazing control, finesse, and breaking pitches. He seldom threw anything that resembled a fastball. On one occasion, while with Fort Worth, Walkup faced Babe Ruth three times in an exhibition game. The Babe fanned all three times. A miffed Ruth angrily downplayed Walkup’s success against him, “I can kick’em up there faster than he throws, that’s why I am in the big leagues and he ain’t.”

Walkup might have been 5’8,” and he supposedly weighed 150 lbs. In many old team photos, he resembled a batboy. Despite Ruth’s evaluation, in the late spring of 1927, Lefty Walkup got his one and only chance with the Detroit Tigers. The brief big league “cup of coffee” included another encounter with the Great Bambino and his “Murderers Row” teammates who made up the 1927 Yankees.

Walkup’s stay with the Tigers was brief, but one of his two appearances was against a team sports writers like to call the greatest lineup of all time, the 1927 New York Yankees. It was Monday, May 16, 1927, and the wind off Lake Michigan brought a winter-like chill to Navin Field. Sunday’s game had been snowed out, and only about 4,000 brave fans rattled around the spacious stadium for the last game of the series. Of course, most were there to see Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and the other stars of the intimidating visitors from New York. Even the mighty Yankees could not entice more fans on a day James Harrison of the New York Times declared those attending “should have had more sense.”

The Yankees were one month into a season that would become legendary and a benchmark for measuring great teams in the future. It would be remembered as Babe Ruth’s signature season, and the Yankees of 1927 would become a team for the ages. Yankee fans who later followed DiMaggio and the Mick, Reggie, and A-Rod could readily recite the lineup of the ’27 Yanks. The batting order on that May afternoon featured Combs and Koenig at the top of the lineup, followed by “Murderer’s Row” of Ruth, Gehrig, Meusel, Lazzeri, and Jumpin’ Joe Dugan. This was a lineup that would set a standard for intimidating pitchers for years to come. It was on this mostly ignored and inauspicious stage, that a little lefthander from the foot of Mount Magazine, Arkansas would make his final appearance in the “show.”

Walkup had pitched the last inning of a game with the Cleveland Indians two weeks earlier and had given up a run in the 9th in a 6–2 loss. On this cold day in Detroit, Lefty Walkup would come face to face with baseball history’s most legendary heroes and exit the big leagues forever.

Entering the ninth inning, the Yanks were up 4-2. Gehrig had a homered in the third and drove in another run with a double in the seventh. George Smith had pitched a successful eighth inning against the Yanks but the ninth would be far different.

Yankees catcher Pat Collins walked to start the inning. Pitcher Dutch Ruether, a good-hitting pitcher, batted for himself and grounded out. Smith proceeded to walk Earle Combs and Mark Koenig to load the bases. At this point, Tigers’ manager George Moriarty called for the little lefty from Arkansas. Of course in the movie-script story of Lefty Walkup, the first batter he faced was Babe Ruth. The Great Bambino probably remembered Walkup’s success in the exhibition game a few years earlier.

This time he greeted Walkup with a single, scoring two runners the little lefty had inherited from Smith. Somehow the youngster righted himself and ended the inning with harmless pop-ups by Lou Gehrig and Bob Meusel. Jim Walkup’s part of history would be relegated to a line in an obscure box score in the Yankees’ glorious 1927 season.

Looking back, however, through the perspective of Arkansas baseball history, the story of Jim Walkup has a much larger place. The odds against a youngster from Havana, Arkansas, making the major leagues are overwhelming at best, but to have that small moment in time facing Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig gives Walkup’s last major league appearance a unique significance. The runs that scored on Ruth’s single were charged to Smith, therefore Walkup’s official line for the 2/3 of an inning’s work would show no earned runs allowed.

If the story of Jim Walkup’s baseball career ended on that cold day in 1927 it would be an intriguing story, but only his major league career ends that day in Detroit. Walkup, like so many young hopefuls in those days, was a baseball player by profession. He would return to the minors and win more than 100 games in the next eight seasons. Most of that time, he was back with Fort Worth in the Texas league where he was a bona fide star.

Jim Walkup retired in 1934 with 259 minor league wins, one of only a handful of Arkansans with more than 250 career wins. Walkup spent most of his working career as a baseball player. His years in pro baseball paralleled one of our country’s most difficult eras. Walkup’s career was interrupted by World War I, and he enjoyed his best professional years during the Great Depression. Although he pitched in two major league games, he is best described as a career minor league pitcher. He played 17 seasons during a 20-year period and pitched nearly 4,000 innings. Only two of those games and less than two of the innings were in the major leagues.

The interesting part of his story in comparison to today’s sophisticated minor league farm systems is that Walkup was allowed to stay in the minors for 17 years. In today’s baseball world, he would have been immediately released when some coordinator of minor league pitchers decided he would never be a major league pitcher. In Walkup’s day, he was not only allowed to stay in the minors, he was welcomed.

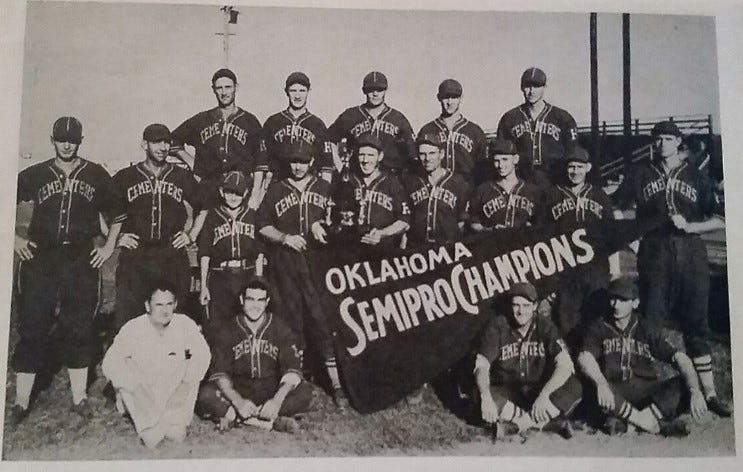

The year Jimmy retired from professional baseball, his cousin, James Elton Walkup, made his first appearance with the St. Louis Browns. In 1936, Duncan, Oklahoma, won the Oklahoma Semi-pro State Championship. Their ace pitcher was 41-year-old Lefty Walkup.

Orville Armbrust Spoils Babe’s Last Game as a Yankee

On September 30, 1934, in the season’s final game, Babe Ruth played in a Yankee uniform for the last time. Coincidently, the Washington Senators’ pitcher that day was pitching his last major league game but without the fanfare of Ruth’s departure. The Senators’ rookie hurler was only 26 years old, and it was his third appearance in his first major league season. While those in attendance knew that at age 39 the Great Bambino was finished as a Yankee, few suspected the rookie was making his last appearance in the big leagues.

Legendary sportswriter Shirley Povich (yes Maury’s father) described the historical significance of the day in the elaborate hyperbole that made him famous.

The Babe bowed out yesterday.

The end of a 22-year trail, strewn with records fashioned by his bludgeoning bat, greeted Babe Ruth at Griffith Stadium where 12,000 assembled to watch the King of Diamonds abdicate. It was his last game as a regular with the Yankees, a voluntary relinquishment of his post.

Babe bowed out as a loser, what with the Yankees dropping a 5-3 decision to the Nats, but no single defeat could mar the memory of the Big Fellow's deeds of the past, which, after all, were the excuse for the party.

Belongs to Ruth.

Nor did the fact that Ruth's potent bat failed to ram even as much as a single to the outfield terrain against Washington's rookie pitching, cloud Washington's tribute to the Big Fellow. The show belonged to Ruth, as fans who turned out for the ball game, as meaningless as an icicle in Little America, attested. -Shirley Povich, Washington Post, 1934

The Washington rookie pitcher on that historic day was Orville Armbrust, a right-hander in his third major league game. Armbrust was born in Bierne, Arkansas, a timber town a few miles south of Gurdon. His father, a sawmill operator, later moved his family to Crossett, another Arkansas lumber town near the Louisiana border, before settling in Little Rock by the time Orville reached his teens. After being signed by Washington while playing in the Little Rock City League, Armbrust had moved quickly through the Senators’ minor league teams at Memphis and Chattanooga, and the big club wanted to take a look at him at season’s end.

Armbrust had made his debut on September 18 against Cleveland and tossed 2 2/3 innings of scoreless and hitless relief. He appeared again on September 24 against the Philadelphia Athletics and held the A’s scoreless in his three innings on the mound. On September 30, the Yankees would choose future Hall of Famer Red Ruffing to start in Ruth’s last game. The Senators’ manager, Joe Cronin, countered with the 26-year-old rookie, Orville Martin Armbrust, from the Piney Woods of South Arkansas.

The visiting Yankees sent up Frank Crosetti, Red Rolfe, and Ruth in the first inning. If Armbrust was intimidated, he disguised it well. Ruth stroked a well-hit line drive to center for the third out in an otherwise uneventful inning. After the Senators failed to score in the first, the Yanks put a run on the board in the second on a home run by Lou Gehrig. The Yankees scored again in the 4th inning when Ruth walked and scored on an RBI double by Twinkle Toes Selkirk. Down 2-0, the Senators exploded for 5 runs in the bottom of the fifth. The big blow was a bases-clearing triple by right fielder Johnny Stone. Armbrust faced Ruth again in the 6th and retired the Babe on a routine ground out, although the Yanks picked up another run.

After a routine 7th inning, Cronin relieved Armbrust to start the 8th. The Sporting News reported later that Armbrust had suffered an elbow injury in the game, although such an injury was not mentioned for the remainder of his career.

Armbrust’s pitching line for the day was 3 runs, on 7 hits, in 7 innings. He was the winning pitcher. The game made headlines in newspapers throughout the country, not because of the importance of the game, but because it was The Babe’s last game as a Yankee.

Orville Armbrust’s career was off to a promising start. He had won 22 games in the less than two minor league seasons it took him to get to the majors. He was called up in mid-September of 1934 for a 12-day stay on the Washington roster. In his final appearance with the Senators, he beat the Ruth/Gehrig Yankees and outpitched a future Hall-of-Fame pitcher. In his three pitching outings with the Senators, Armbrust posted an excellent 2.13 ERA in his 12-plus innings on the mound. Inexplicably, he never pitched in another major league game.

After a very successful late September in Washington, Armbrust was definitely in Washington’s plans for 1935. Manager Clark Griffith spoke well of Armbrust with some serious reservations. An Associated Press article in early 1935 summed up the manager’s concerns. “Griffith likes everything about Armbrust except his avoirdupois. The fat boy has been shaking off weight all winter and may be down to a normal weight by spring.”

The Senators trained in Biloxi, Mississippi, in the spring of 1935, and when the team broke camp to head north, Orville Armbrust was sent back to his previous minor league home at Chattanooga. He should not have unpacked his bags. Armbrust made five team changes during the 1935 season. He started the season with Chattanooga and also spent time with Albany, Harrisburg, Elmira, and back to Harrisburg for the last two months of the season.

According to BaseballReference.com, Armbrust’s record for 1935 was 8–14, although five team changes and incomplete stats with some of the teams call into question the accuracy of his record. Bouncing around the minor leagues would be the storyline for the last years of Armbrust’s career.

Armbrust started the 1936 season with the Dallas Steers in the Texas League but was released in late June and picked up by Galveston in the same league. Armbrust’s record was a combined 7-10 with the two Texas League clubs.

In what would be a rare year of stability, Armbrust pitched the entire 1937 season for Galveston. His 10–14 record and 4.88 ERA were unimpressive, and 1938 saw him demoted again. This time he was sent down to Class B Jackson, Mississippi of the Southeastern League.

Ironically, with no chance to ever reach the majors again, Armbrust had a good year with Jackson, a New York Yankees farm club. At age 30, he was the oldest pitcher on the team, but he finished with a respectable 15-8 won/loss record and pitched the second-most innings on the team.

On March 14, 1939, a relatively insignificant sports story was tucked away in the corner of the baseball news of the day. It took just over three lines of print to announce that Jackson had given Orville Armbrust his outright release. Armbrust retired from baseball, moved to Mobile, Alabama, and worked in the shipyards until he died in 1967. He was 59-years-old.

Orville Martin Armbrust, the sawmill operator’s son from the woods of South Arkansas, pitched in one of the most watched games of 1934. In these media-rich days, Babe Ruth’s last game as a Yankee would have been nationally televised, and the game would have been the lead story on Sports Center. A crew would have been dispatched to Arkansas to interview Armbrust’s family, and baseball fans would be diligently watching his tweets. In 1934, it was beloved sportswriter Shirley Povich’s job to watch the game for the thousands of fans who had no other way to witness the historic event. Fans “saw the game” the next day through Povich’s eyes and his flowery prose.

And then he went into the ball game. But no semblance of a base hit bounced off his lusty bat. The rookie pitcher, Orville Armbrust, retired him in the first inning on a fly to center field. On his next appearance he was walked. A harmless grounder to Buddy Myer, he drilled on his third trip to the plate.

In one uproarious assault against Red Ruffing, the Nats won the ball game, blasting a 2-0 Yankee lead out of being with a five-run splurge in the fifth inning. Young Armbrust held that lead.

But that ball game had been only an anticlimax. Unlike Hamlet, the Babe, not the play, was the thing. -Shirley Povich, Washington Post, 1934

Perhaps somewhere in a yellowed clipping in Orville Armbrust’s long lost scrapbook, Povich’s words record the day the rookie pitcher from South Arkansas spoiled Babe Ruth’s last game in a Yankees’ uniform.

Hogwash - Running the Gauntlet

After 18 games are there only three teams with a realistic shot at the overall SEC baseball title?

The Hogs host Florida this weekend in the typical SEC baseball war that almost always remains undecided until the last series. Usually, (over the last ten seasons) 20 wins would result in a division title, and 22 or 23 would win the overall title. Winning seven of the twelve remaining games might just win both a division and an overall title for Arkansas, A&M, or Kentucky. Tennessee might need to win eight or nine, but the Vols seem to have a little “easier” schedule.

If the Hogs win the Florida series, the trips to Kentucky and College Station will be pivotal and excruciating. I am hopeful. I really like this team. What do you think?

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Having watched the White Sox in several games against the Royals, I can attest: they are awful. Poor Benintendi--I always liked him.