Backroads and Ballplayers #49

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Starting Year Two and Lost Stories of Survival

This is the first post in the second year of an experiment designed to save some obscure Arkansas baseball stories. I had no idea where Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly was going a year ago. All I knew was that I had a lot of information to share, and I wanted to publish these stories for free.

As of the one-year mark, we have 220 email subscribers, 460+ Facebook followers, and about 400 readers each week. That is far beyond my expectations. Thank you for your support. Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly will always be free.

I do have two books in publication with more in-depth stories. Information for ordering signed books can be found at this website. Backroads and Ballplayers on the Web

Two personal items:

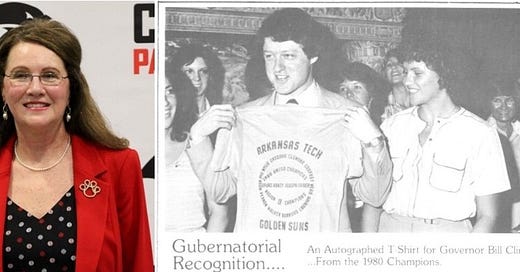

Carla Crowder and the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame

Most of you know by now that, in what seems like another life, I coached the Women’s basketball team at Arkansas Tech. After taking our licks in my first season with an awesome group of over-matched young women, the Golden Suns won four consecutive conference titles.

Carla Burruss Crowder was a key member of three of those championships. On Friday, April 19, Carla will be inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. While the selection indicates “Coaching” was the qualification for her honor, her teammates and I realize her love for the game, unselfish dedication to her team, and unrelenting competitive spirit made her an essential part of the Suns’ championship seasons at Arkansas Tech.

A Tribute to the Franks Baseball Family

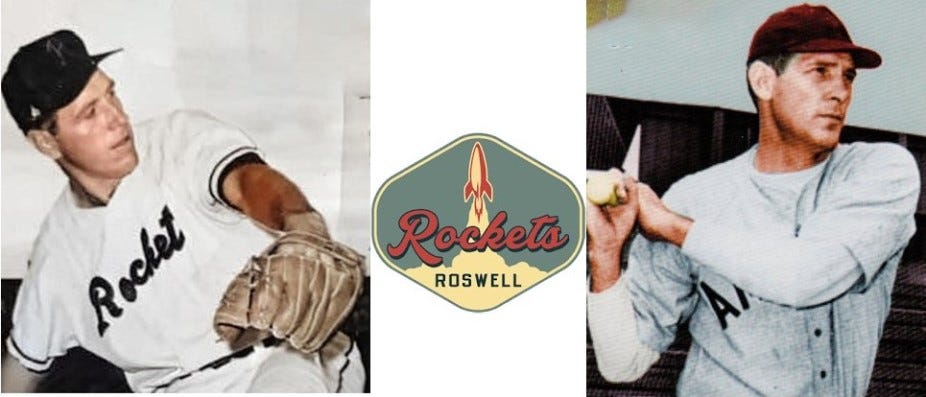

On Friday, April 12, a baseball tale that connected rural Arkansas and Roswell, New Mexico, was the lead story in Only in Arkansas. The story of Dean Franks is one of my favorite research projects. Franks’ baseball life is a quintessential example of what baseball meant to rural Arkansas in the 20th century. Of course, an adventure like this needs to begin in a place called Monkey Run, Arkansas. Please take a look. Link

Lost Stories:

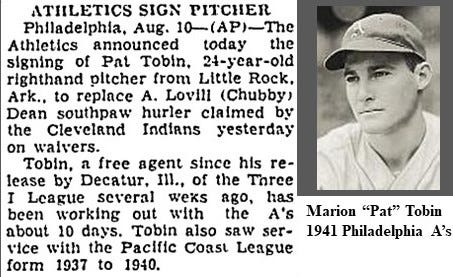

Brooks (Pat) Tobin

In 1955, on the occasion of his retirement as Central Arkansas Semi-pro League Commissioner, Andrew Holland, was asked to identify the outstanding players he had seen in Arkansas amateur baseball over the almost 20 years since the organization’s inception. While he mentioned an outstanding young infielder named Brooks Robinson was just getting started in the pros, Holland listed Marion Brooks Tobin as the most outstanding player in Little Rock semi-pro baseball from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s.

Tobin preceded Brooks Robinson in reaching the big leagues by more than a dozen years, but his time as a major leaguer was one of those “cup of coffee” careers that are lamentably brief. Robinson played more big league games than any Arkansas-born player. (2848) Marion Tobin played in one!

There was little in his minor league resumé to indicate that Tobin would forever carry the honorary distinction of “ex-major-leaguer.” He is, however, the ultimate example in Arkansas baseball history of a player who was in the “right place at the right time.”

Marion Tobin was born in 1916 to Annie and Cleveland Tobin, who were raising three young sons operating Tobin Mercantile in the almost thriving little town of Hermitage, Arkansas. Hermitage had a train stop, a burgeoning timber industry, and a few local farmers were experimenting with tomato farms as a cash crop. The Tobin’s store occupied a new brick building in “downtown” Hermitage and business was good.

All that changed in March of 1920, when Annie became a widow at age 27. The young single mother soon gave up Tobin Mercantile and left Bradley County for a house on Marshall Street in Little Rock. The three Tobin sons: Louis Belin, Marion Brooks, and Daniel Harrison, grew up on the playgrounds and ball fields in Little Rock.

First Belin, and later Marion, became well known on the sandlots and gyms of Little Rock. YMCA basketball was the winter choice for the Tobins, but it was summer baseball where middle son Marion emerged as a local prodigy. Marion’s name could be found in local newspapers most summer mornings in the early 1930s pitching for American Legion teams and simultaneously in several men’s semi-pro leagues. One independent team in the Twilight League, featuring brother Belin on the infield and Marion on the mound, was simply called the “Tobin Nine.”

In April 1933, despite some attention from pro baseball, 17-year-old Marion Tobin joined the US Navy. With most of the Navy activity centered on the Pacific Coast, Tobin was assigned to the American Fleet in San Diego, California.

Peacetime with the fleet left plenty of time for baseball. The games between ship teams were highly competitive and prominently featured on local sports pages. Marion Tobin, now known in the press as “Pat,” was a headliner in fleet games as a pitcher for his ship team.

West Coast minor league teams liked what they saw in the young Arkansan. Tobin was offered a contract by Sacramento in 1936, but his discharge request was denied. In April of 1938, he made another request, and this time he was granted an honorable discharge. Tobin signed with the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres. A few months later, his shipmates were deployed to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, to defend the Pacific Fleet.

Tobin spent most of the next three seasons struggling on the mound in the highly competitive PCL. By the beginning of the 1941 season, he had been demoted to the low minors and seemed to be on his way out of pro baseball.

Tobin started the 1941 season in Class B Decatur with some success until a foot injury in mid-June initiated a steep decline in his control. His wildness woes included a game on June 25th that saw him walk 13 batters, prompting Decatur to release him in early July. Although it looked like his baseball career was over, Tobin would get one more implausible chance.

While there was little in Pat Tobin’s credentials that merited a promotion to the major leagues, he had once been a top prospect in the PCL. That was good enough for the Philadelphia Athletics, the American League’s worst team. On August 10, 1941, Pat Tobin was signed by the Athletic’s legendary Connie Mack.

Eleven days later, in a game with the Browns in St. Louis, Tobin would get his chance. Jack Knott, the A’s only starter with a winning record, had fallen behind 6 - 2 when Mack called for Tobin to pitch the 9th inning. Unfortunately, the looming shadow of Tobin’s control problems had followed him to the major leagues.

A’s shortstop, Al Brancato, booted a ground ball to start the 9th. A single and a sacrifice bunt left runners on second and third with one out when Tobin’s chronic wildness returned. He walked the next two batters to force in a run. Three consecutive singles put the game out of reach at 10 - 2, but Mack obviously decided to let Tobin finish the hopeless cause. He retired the next two batters on a flyout and a foul pop-out to the catcher, mercifully ending his only major league inning.

Four months later, on December 7, 1941, Pat Tobin’s former shipmates were aboard the USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, when the Japanese bombed the American Fleet anchored there. Tobin was spending the off-season in Little Rock when he learned that almost 1200 of his shipmates had perished in the attack. Had it not been for his discharge to pursue pro baseball, Marion Tobin would have been on the Arizona that fateful day.

Tobin made local headlines again in September of 1944 when his Spaulding League All-Stars won the semi-pro state championship. Tobin’s photograph appears at the top of the sports page after he capped a 10th-inning finish by striking out the side on the mound in the top of the inning and hitting a walk-off homer to win the game in the bottom of the frame.

Tobin continued to play in Arkansas’ semi-pro leagues throughout the 1940s before moving to Shreveport to become an insurance executive. He died of a heart attack in Shreveport in 1975, at age 58.

A more complete story can be found in Backroads and Ballplayers P.187

An Ill-fated Possum Hunt

On March 10, 1938, the Evansville Press ran a small story concerning a mining accident, tucked away on page 13. Falling shale in the Little Betty mine near Linton, Indiana, had taken the life of a local miner named Harry H. Allemang. Ironically, the minimal news item was the second time Allemang’s death had made the local papers. The first time, 35 years earlier, had made sports page headlines.

Sources of reliable information were minimal and communication systems were woefully primitive in the early 20th century before baseball was considered the National Pastime. This dearth of accurate sports reportage was obvious in January of 1903 when Harry Allemang sent letters inquiring about pitching jobs in professional baseball, beginning with the assurance that he was positively not dead.

Harry H. Allemang was born in Nile Township in the rural southeast corner of Ohio on December 21, 1876. Unsophisticated and unaccustomed to the ways of the world, he soon earned the often-used baseball nickname “Rube” when he entered professional baseball in his early 20s.

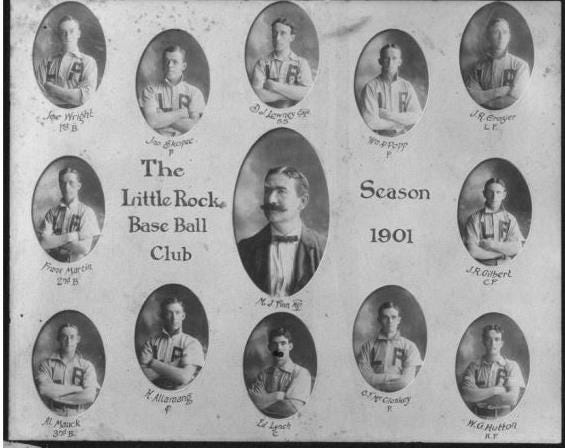

The young county boy did not have immediate success in the minor leagues. In 1900, pitching for the uniquely named Youngstown Little Giants/Marion Glass Blowers, Allemang won four games and lost fifteen on a dismal club managed by soon-to-be Little Rock field boss, Mike Finn. In an example of Finn’s uncanny ability to judge baseball talent, he saw something in Allemang that was well hidden in his record. When he was hired the next year to manage Little Rock’s new team in the Southern Association, Allemang was the first pitcher Mike Finn hired to go south with him.

The 1901 Travelers won the pennant on the field only to lose it in an unfriendly board room a month later. The ace of the pitching staff was that 25-year-old mountaineer from rural Ohio named Rube Allemang. In fact, Allemang was the best hurler in the Southern Association, with a 20 - 4 record and a .833 winning percentage. The Arkansas Gazette described the Trav’s ace as “The Flaxenhaired Virginian…the best pitcher in the South.”

The 1902 edition of the Little Rock Travelers finished a competitive second in the Southern Association and Allemang remained the team’s mound leader. His 19 victories tied for the club lead. St. Louis and later Cincinnati made offers to promote the 25-year-old right-hander to the major leagues. The Travs accepted the Reds’ $500 bid. A successful career in the big leagues seemed inevitable, but fate was about to throw the young pitcher an unhittable curve.

In the early morning hours of November 9, 1902, Allemang’s promising career took an ominous turn in his off-season home in the small mountain village of Mason, West Virginia. After separating from his possum hunting party at about 3:00 AM, Allemang was walking home alone near the Mason post office when he happened upon a man posted as a lookout for a robbery in progress. Warned to stop, Allemang approached the crime guard and was shot in the chest as he neared the door. The bullet passed through a lung and came to rest against his spine. Somehow, Allemang crawled to a nearby residence, and a local doctor was summoned. The country doctor offered little hope.

Back in Little Rock the local newspaper broke the news to Allemang’s Arkansas fans in a front-page headline, “Allemang Shot, May Not Recover.” The accompanying news story left little doubt about the expected outcome. “All the news that could be gleaned last night, after diligent wire-working, with reference to Allemang’s condition, was that his wound was fatal. His death is evidently a question of only a short time.”

Ohio newspapers were more resigned to a fatal result. The Cleveland Plain Dealer ran the headline, “Fatally Shot By Robbers, Harry Allemang a well-known ballplayer discovers safe-blowers at work and is mortally wounded.”

Despite the hasty predictions of his eminent death, after a month in the hospital, Allemang recovered. Unfortunately, recovering sufficiently to be dismissed from the hospital was not an indication that he would return to major-league pitching form. He had been hit just above the heart, with the bullet passing through his right lung. His remarkable recovery puzzled local physicians and he was determined to pitch in the upcoming season. While still in the hospital, he sent a letter to Reds owner August Herrmann to “Let you know I am still alive and expect to report in the spring.”

In January of 1903, Little Rock manager, Mike Finn, received the $500 check from the Cincinnati Reds to fulfill their end of the bargain. The Reds had purchased one of the most promising young pitchers in minor league baseball, but they were not going to get the Harry Allemang they had scouted in Arkansas.

Cincinnati manager, Joe Kelley, quickly realized in spring training that Allemang was not a major-league-caliber pitcher and before the Reds opened the National League season the manager demoted him to Toledo in the American Association. The Class AA league was a formidable challenge for the weakened young pitcher who had spent a month in the hospital and still had a bullet lodged in his back.

In an early season game typical of Allemang’s diminished skills, he entered a game with Minneapolis in the third inning with the Mud Hens down 6 - 2. Six innings later the game was called early by mutual agreement with Minneapolis ahead 24 – 2. Allemang had given up 18 runs in five innings of work. A few weeks later he was released and picked up by a pitching-desperate St. Paul club in the same league.

Allemang got a full season to reprove himself with Class AA Indianapolis in 1904, but his dream of a long successful major league career was squelched beyond doubt. Although he managed to win 10 games, he lost a league-leading 23 times. His ERA of 5.79 was an indication that his injury had taken a career-ending toll.

Rube Allemang got a two-game trial in Sioux City in 1905 and a six-game shot in Nashville in 1906. His old manager from Little Rock had taken the Nashville job and undoubtedly remembered his ace pitcher from three seasons past. Unfortunately, Rube was a very different pitcher from the “Best Pitcher in the South” of 1902.

Allemang gave up baseball and settled in the coal mining region of Indiana. He returned to the coal mines until the fatal accident in the Little Betty mine ended his life in 1938. Harry Allemang was 61-years-old. Few locals were likely to have known the story of a promising young pitcher from 35 years past.

A more complete story is available in Hard Times and Hardball. P. 15

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/