Backroads and Ballplayers #47

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Building the Airplane in the Air

To say the Dodgers did not have a smooth opening to the season would be a California-sized understatement. After winning their season opener in Seoul, Korea, things began to deteriorate just a little.

In the second game of what was designed to be a celebration of American baseball, the Dodgers held open tryouts for relief pitchers and didn’t find one. Their rookie pitching investment pitched one really bad inning, and they had to answer a few hundred questions about this little gambling thing. As an aside, they lost to the Padres 15—11.

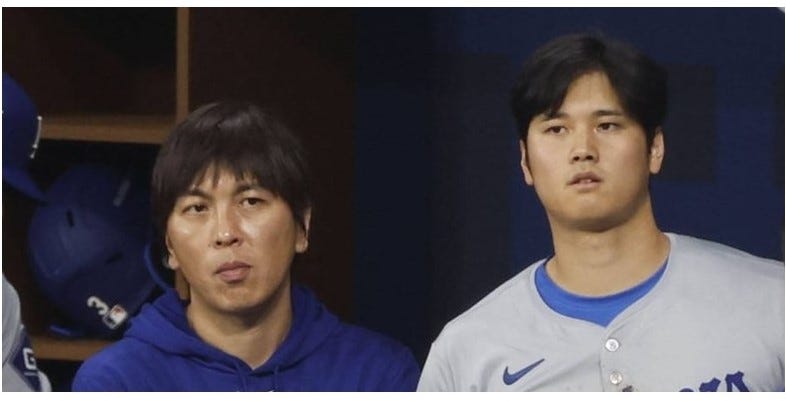

No one seems to be talking about the games in Korea, and the principals in the off-the-field drama are not talking at all. As I write this on Sunday, the headline on the ESPN website is an examination of the Ohtani story that is two days old. ESPN simply had nothing new to report. I would say all the players in this drama are sequestered somewhere learning their lines!

This just in…Ohtani is going to talk today (Monday). Is he going to answer questions? It should be a revealing news conference. The Athletic reran their three-day-old piece today. The article by Ken Rosenthal with an unanswered questions theme is longer than this entire post. Good luck Shohei.

Since he arrived, Ohtani has been protected by his language barrier, excused by his naivety, and shielded by his entourage. He is about to learn a very difficult lesson about his special handle-with-kid-gloves status. His “favorite of the press” credentials are about to be revoked. I sincerely hope he passes the scrutiny of what is about to be a highly public investigation. Baseball needs him, and he is probably a very good guy!

The first story that Shohei had paid off his friend’s gambling debt did not work. It made Ohtani a felon! The current story seems to be that Ohtani’s longtime friend and interpreter, Ippei Mizuhara, stole at least $4.5 million from Shohei to pay off illegal gambling debts. I would suppose that before this post is a week old the prevailing story will have several revisions.

Dylan Hernández of the Dodgers’ hometown newspaper the LA Times, was more than blunt. “Ohtani has to grow up. Longtime interpreter Ippei Mizuhara’s firing this week should be a warning to him. For too long, Ohtani has taken responsibility for little besides his on-field performance.”

Even Joe Postanski, level-headed scribe, and Ohtani fan, had to admit, “This story is still very much in doubt. It’s either the public relations catastrophe of all time or an attempt to cover up something (or, alas, both).”

What do you think?

Flying in From the Bullpen

It is played everywhere. In parks and playgrounds and prison yards. In back alleys and farmers’ fields. By small children and by old men. By raw amateurs and millionaire professionals. -Narrator John Chancellor from Ken Burns Baseball Documentary

Although things like this can be difficult to determine, The Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia gives the designation of the first game between town teams to a well-publicized contest held on Independence Day, 1868. The contest matched a team calling itself the “Rock City Base Ball Club” and a contingent of farmers from Pine Bluff.

The visitors arrived two days early to immerse themselves in the excitement of the upcoming contest. Newspapers carried the story on the front page, and a shaded seating area was hastily constructed to protect the delicate city folks from the mid-summer sun.

The game lived up to expectations. The two teams battled until both daylight and energy were in short supply, with Rock City eking out a 43–36 victory. In a show of goodwill: “Three cheers were made, as well as a ‘tiger’ for the umpire.”

By the turn of the century, professional baseball had emerged and failed in most of the state’s larger cities and towns, but town-team baseball had become the sports event of choice. Sunday picnics and baseball were the most favored summer social events in Arkansas communities. Soon, more organized leagues emerged, and roster rules were created to eliminate teams from recruiting players with no connection to the community they represented.

One of the most influential men in the growth of what newspapers began to call “semipro” baseball was Dr. Earl Williams of Greenbrier. A country doctor with a passion for baseball, Williams created the Faulkner County League in 1916. The league had a master schedule, standings, and a rule that players on each roster had to live within three miles of the post office they represented. For the next 30+ years, the little village in Northern Faulkner County was the epicenter of amateur baseball in the state, and Dr. Williams became Arkansas’ “Dr. Baseball.”

Naturally, teams began calling themselves champions of various leagues, and, eventually, especially successful squads claimed to be the “Arkansas State Champions.” Without a formal contest to declare a state champion, a team’s declaration that they were the state’s preeminent baseball team met with some disagreement.

A semipro team in a different location would take exception and issue a challenge. If the “champion” team agreed, the two teams met to establish the true title holder, at least until the next challenge. The process continued until the cold winds of fall made Sunday afternoon games intolerable, or until the various challenges made it impossible to know who was the authentic title holder. The controversy over which team was the state semipro champion continued until the mid-1930s when the creation of a national championship motivated local semipro leagues to become more organized.

A somewhat risky venture called the National Baseball Congress held its first championship in Wichita, Kansas, in 1935. A penniless entrepreneur named Ray Dumont created the event, and to stimulate some fan interest, he paid Satchel Paige an appearance fee to bring a racially mixed team from the Dakotas.

Perhaps because of Paige’s involvement, the National Baseball Congress worked, and the national organization for semipro baseball was born. Dumont recommended that states create an official state tournament and choose a team to represent the state at the new NBC World Series.

In 1937, Arkansas sent its first NBC-sanctioned state champions, the Beirne Lumbermen, to a regional qualifying series against the Oklahoma champs. Beirne swept the Pitcher, Oklahoma, squad to become the first Arkansas representative to the NBC World Series in Wichita, Kansas.

By 1938, Arkansas had made Dr. Williams the Commissioner of Arkansas Semi-pro Baseball. He was the unofficial godfather of amateur baseball in the state, and Willimas and his sons had announced the creation of a “baseball summer school,” in Greenbrier. Unlike the Doan School in Hot Springs, located in one of the state’s most wide-open towns, the Greenbrier was “mom-approved.” Publicity boasted a baseball-centered environment in a town without honky-tonks and pool halls.

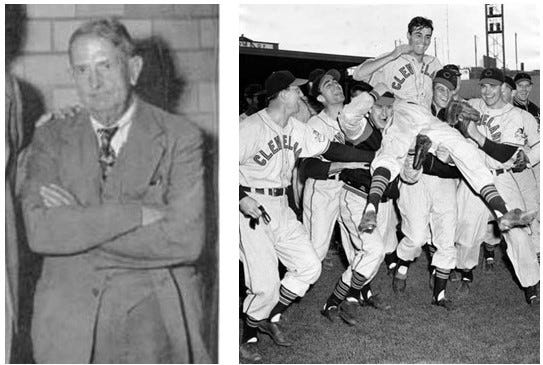

When the state semi-pro tournament opened in mid-July the Greenbrier Baseball School was the favorite to take home the title. Williams entered two teams, his best students made up Greenbrier Baseball School Number 1 and featured future World Series hero Gene Bearden. A second entry was designated as Greenbrier Baseball School Number 2.

Greenbrier Number 1 made it to the finals without a loss. Their opponent, the Little Rock Research Hospital, had worked through to the losers bracket with their ace Bryan Hammett pitching in every game.

Bearden lost to Hammett in the first game of the doubleheader to decide the championship 7–1, but with their only dependable pitcher used in game one, Little Rock Research Hospital was out of pitchers. Greenbrier Baseball School still looked like the team to beat.

Hammett had pitched a complete-game victory in the first game, and, at best, he could only offer a few innings in the deciding game. With a state championship and some professional pride at stake, a Little Rock doctor with ties to Research Hospital commandeered a private plane to fly an eligible pitcher, Ed Herndon, from Little Rock to Fort Smith, the site of the tourney.

With the fly-in pitcher holding the tough Greenbrier lineup in check until Hammett relieved for the last two innings, the Little Rock squad prevailed 5–3. Hammett was credited with the win in both contests. It was not William’s last tough loss in the state tournament. The next year a team from Ozark defeated a new Greenbrier Number 1 in the finals of the state tournament. Although he is credited with the success of amateur baseball in Arkansas, Dr. Baseball never won a state semi-pro title.

October 2, 1949

The careers of baseball Hall of Famers are sprinkled with big moments. Sometimes those defining events happen in the heat of a pennant race, or the deciding game of the World Series. Perhaps, the Future Hall of Famer hits a walk-off home run, strikes out a batter with the tying run at third, or makes an Enos Slaughter dash from first on a presumed single to score the go-ahead run in the final game of the World Series.

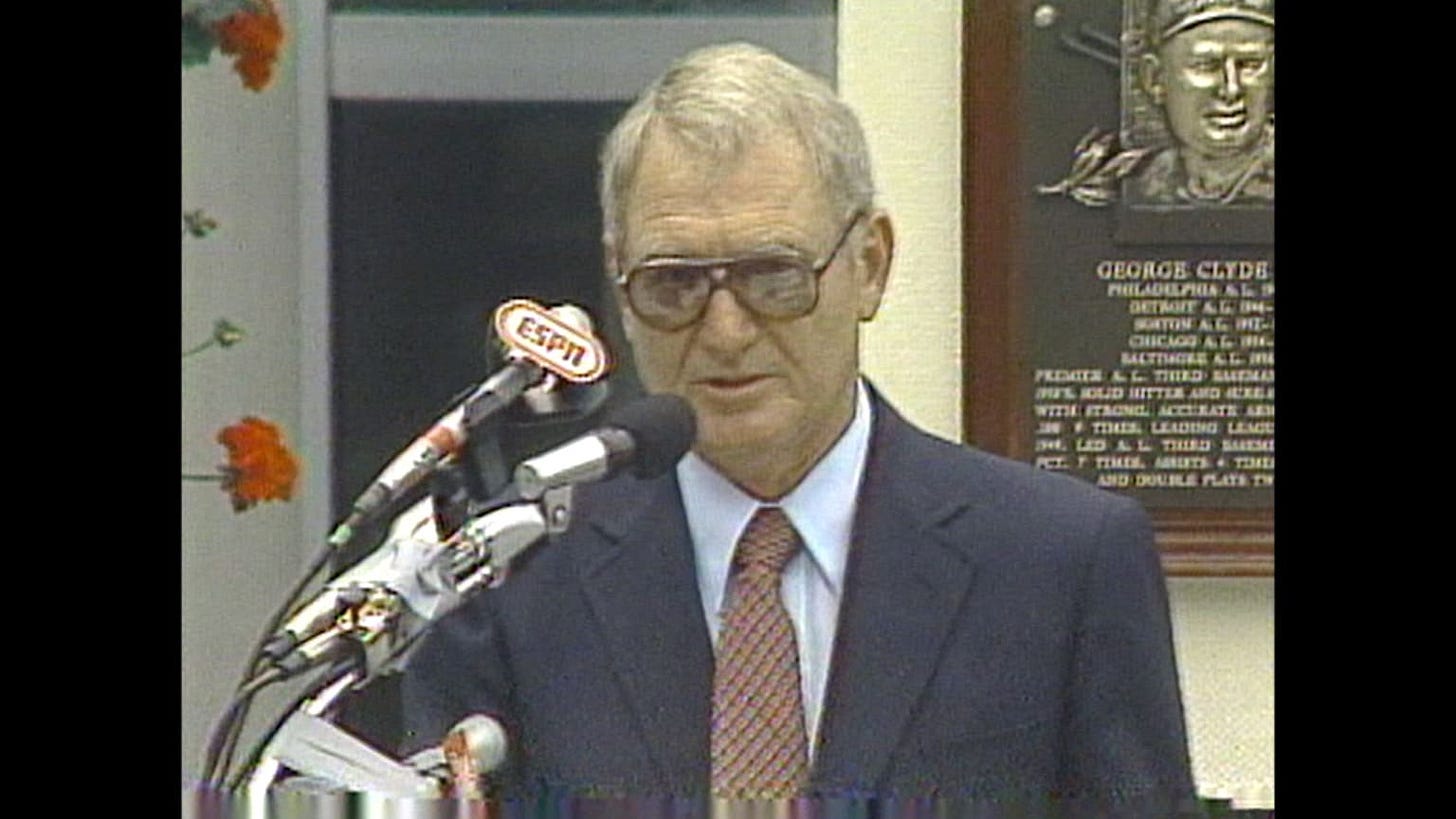

In the case of Swifton, Arkansas’ George Kell, one of the most exciting moments of his career happened in the last game of the 1949 season. The Tigers were playing Cleveland, but the only thing at stake for the two teams was third place in the American League. In the bottom of the ninth with Cleveland safely ahead 8-4, Kell’s memorable moment occurred with him in the on-deck circle.

One modern baseball writer surmised: “George Kell is in dire need of a publicist.”

Kell went about his work without celebrity status, controversy, and certainly without self-promotion. He was also the classic Southern Gentleman; an outstanding baseball player, whose standards of right and wrong could have cost him his place in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Here in Arkansas, he is our guy, and the intersection of events, that led to George Kell and Brooks Robinson being inducted on the same day in 1983 made their enshrinement even more special.

On Kell’s plaque in Cooperstown, a line in the inscription reads, “Batted over .300, 9 times, leading league with .343 in 1949.” Was that Batting Championship in 1949 the most significant piece in Kell’s accomplishments that led to his selection by the Veterans Committee in 1983? If so, his Hall of Fame induction came down to the last at-bat of the Tigers’ 1949 season.

Kell described his conflicted feelings as he waited in the on-deck circle for his last at-bat in 1949. It was a plate appearance that he did not want to happen. “I really didn’t want to bat, but I couldn’t see putting in a pinch hitter for me in that situation,” Kell recalled later. He would be fourth up for the Tigers in the bottom of the ninth, and sensing Kell’s dilemma, manager Red Rolfe asked if he would agree to a pinch hitter if the Tigers got a runner on and reached his spot in the batting order. Anyone who knew George Kell would have been confident in his reply, “No, I’ve got to hit.”

The last day of the season had started with the great Ted Williams leading the league with a .344 batting average and Kell three points back at .341. In Kell’s mind, the batting race was over. Gaining three points on the man some regard as the best hitter in baseball history seemed unrealistic, but, in the late innings of that final game, the press box got the message that the improbable had happened. Williams had gone hitless. Kell’s two hits in three at-bats had given him a precarious lead, but an out in one more at-bat would certainly cost him the coveted batting title.

When pinch hitter Dick Wakefield singled with one out, Kell took his place in the on-deck circle. Many major leaguers with the tough choice Kell faced that day would have opted for the pinch hitter and clinched the American League batting crown. That is not the way things were done in Swifton, Arkansas.

While agonizing in the on-deck circle, waiting for his turn at the plate that could cost him the tenuous lead for the top batting average, fate intervened on George Kell’s behalf. With one out and a runner on first, Eddie Lake’s ground ball to short turned into an inning-ending double play. Kell had edged out Ted Williams in one of the closest batting average races in baseball history. (Kell - .3429, Williams - .3428) The sight of the on-deck hitter jumping up and yelling with joy after an 8–4 defeat had to be one of the strangest images of the 1949 season.

Is a batting crown the item in Kell’s resumé that moved his credentials to the tipping point? Did one ground ball to shortstop that resulted in a double play open the doors in Cooperstown to George Kell? Those are questions that can’t be answered. We do know that Kell was the Batting Champion of 1949. His plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame verifies the accomplishment.

Premier A. L. third baseman of the 1940s and 1950s. Solid hitter and sure-handed fielder with a strong, accurate arm. Batted over .300 9 times, leading the league with .343 in 1949. Led A. L. third basemen in fielding pct. 7 times, assists 4 times, and putouts and double plays twice. -George Kell’s Hall of Fame Plaque

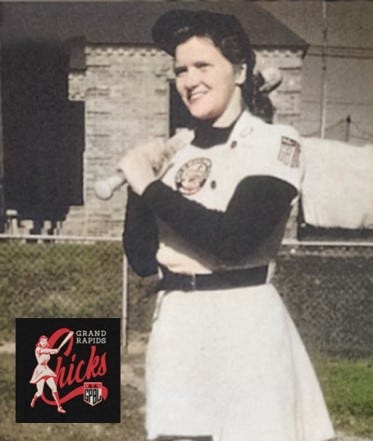

March is Girls and Women in Sports Month - I wrote a tribute to Mid Earp in Only in Arkansas.

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/