Backroads and Ballplayers #46

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Missed Opportunities, Rabbit of the Ozarks, and Hogwash

It seems my readers like the “Lost Stories” series. I hope you enjoy the two new ones in this post.

Subscription Milestone, Thank you!

The subscriber roll for Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly has now topped 200 and the average weekly readership is well above 400. I appreciate your acceptance of this project. Always free!

Question: Why don’t I always get your weekly posts?

You only receive this column in your email by subscribing. You certainly do not have to subscribe, but if choose not to subscribe you have to go looking for the weekly posts on my Facebook page. If you follow Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook, you still have to go to the page to access these weekly posts if you do not subscribe.

If you are not sure if you have subscribed, please email me. backroadsballplayers@gmail.com

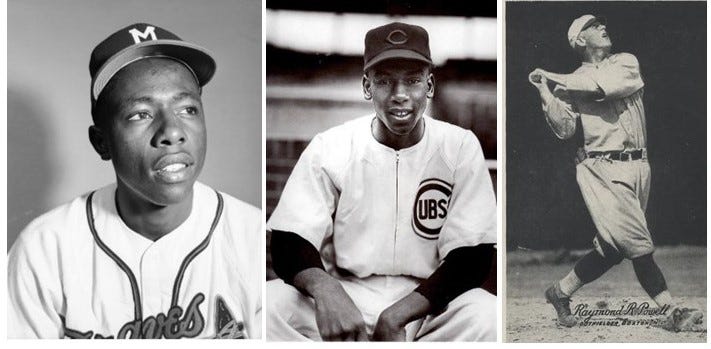

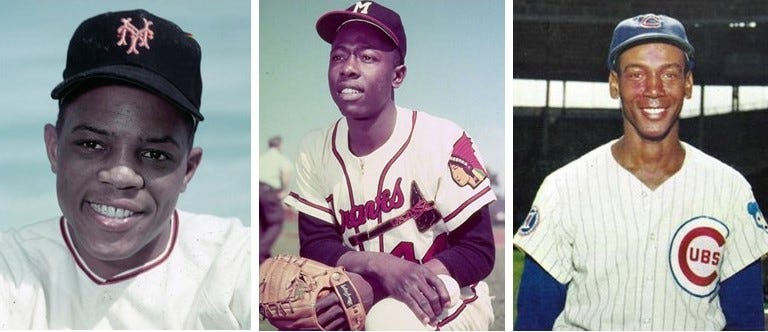

Lost Stories: Mays, Aaron, and Banks in Arkansas

On June 1, 1991, Susan, my sons, and a couple of assorted friends were part of an announced crowd of 12,246 at Ray Winder Field to see Fernando Valenzuela pitch against the Travs. That was a record crowd, but what if it had been a Future Hall of Famer like Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, or Ernie Banks? Arkansans never got to see players of that caliber!

Actually, a few decades before Fernando drew double the capacity of Ray Winder Field, Arkansans had that chance, not just once, but several times. If you didn’t know that, don’t feel too bad. I knew that major leaguers played exhibition games in Arkansas, but the number of times they played to thousands of empty seats was news to me too.

I got into this rabbit hole when I was contacted by a baseball historian from New York, named Wayne Lowrey, who was researching a barnstorming team composed of Black major leaguers. Wayne asked for some boots-on-the-ground help documenting the team’s games in Arkansas. Since I am a sucker for a good mystery, I was all about looking into games the team played in Little Rock and maybe Pine Bluff. It was pretty challenging until Tom DeBlack invited me to lunch.

I mentioned in my last two posts that a few weeks ago, I had one of those days that only seems to happen in Arkansas. At lunch, with some of DeBlack’s retired college professor friends, someone asked why I was in Conway. I replied that I was looking for evidence that Aaron, Mays, Banks, and other great Black major leaguers had played some barnstorming games in Arkansas.

Before I elaborated, a guy in a baseball cap who looked several years younger than me, replied, “That would be October 10, 1955, I was there!” University of Central Arkansas Professor Emeritus, Dr. Joe Whitehead was indeed in attendance for the game on October 10 at Travelers Field between the Black major leagues and their traveling opponents, the Negro League All-Stars. It seems Arkansas Tech baseball player Joe Whitehead and some friends drove down from Russellville and saw the game.

Maybe 2,500 folks were there. Dr. Joe saw Willie Mays hit a homer to right-center field in a ballpark where home runs usually go to become F8s. He saw the young guy who would eventually pass Babe Ruth on the all-time home run list. A twenty-one-year-old Henry Aaron was coming off a pretty good rookie year, but was not yet the “Hammer.” He had three singles and a double in the Little Rock game.

Since the Dodgers had finally won a World Series, some called that 1955 assemblage of major leaguers the Don Newcombe All-Stars, but Sad Sam Jones was the starting pitcher for the big leaguers that evening. Jones was an intimidating fellow who led the league and strikeouts and walks on several occasions, often in the same year. No one dug in against Sad Sam.

Joe Whitehead was about 19 years old in October of 1955. His memories of that night in Little Rock are the detailed recollections of an adult. Dr. Joe even recalled that Jim “Junior” Gilliam was smoking a cigarette while playing second base and that the big leaguers won 11-5. By the way, to add more fortunate implausibility to this meeting, Dr. Joe Whitehead is from Ozark, Arkansas, my hometown. He knows that “you just can’t hide that Hillbilly Pride.” Meeting him was an honor and a very special day in my life. I am sure Dr. Joe is exactly the kind of source Wayne Coffey is looking for.

Later in the treasure hunt, Caleb Hardwick, from the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia found an obscure article in the Sporting News that provided some details about the barnstormers’ game the following Friday. In the Pine Bluff game on October 14, Mays hit two home runs and made what the Sporting News called a “circus catch.” Perhaps someone in Pine Bluff recalls that game.

My friend Jim Rasco located the team’s complete schedule, and Dr. Billy Higgins shared photos of an autographed program from a game he saw in Fort Smith where a similar team played in 1956. A section in the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia refers to several more. Sadly, the exhibitions in Arkansas went virtually unnoticed when they occurred and are now lost stories in Arkansas baseball history.

Negro League and Black major league players - Games in Arkansas. Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

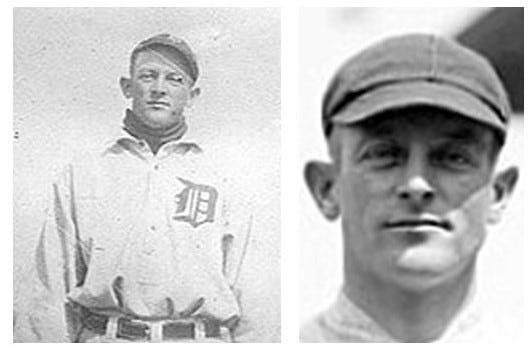

Lost Stories - The Rabbit of the Ozarks and May 1, 1920

On May 1, 1920, the Brooklyn Robins and Boston Braves played an extra inning game that was called “on account of darkness” with the score tied at one. That untimely conclusion is not that rare, but this particular game was historic. Arkansas had an eyewitness to that extraordinary game. Our guy Raymond Reith Powell was the Boston center fielder. Maybe you know him best as “Rabbit” Powell, or more likely you have never heard of him at all. His anonymity is a mystery.

According to the Arkansas Encyclopedia of Baseball, Brooks Robinson, one of Arkansas' most honored baseball sons, played more professional games (minor league + major league) than any Arkansan in baseball history. Second in games played by an Arkansas native is perennial Gold Glove center fielder Torii Hunter. The player ranking third is a little more obscure. Raymond Reith Powell is seldom mentioned in the same conversation with Robinson and Hunter, but for a time in the first quarter of the 20th century, he was among the best in major league baseball at his position.

Born in 1888, Powell grew up in the far corner of Northwest Arkansas near Siloam Springs, and at various times he called nearby towns in Oklahoma and Missouri home. Tagged with the nickname “Rabbit” because of his quickness and speed, he was the prototypical Arkansas country baseball player. He fished, hunted, and played baseball with time left over from helping his parents eke out an existence for a family of ten on an Ozark Mountain farm.

Ray Powell was not yet 20 years old when he broke into pro baseball. The teenage farmboy signed with the Class D Bartlesville Boosters in 1908 and began a journey through the backroads of pro baseball with inconsistent success. Powell simply wasn’t a big-league hitter, but he could run and cover center field like no one else in the minor leagues. In 1915, he was exactly what the Braves were looking for.

Boston Braves owner, James Gaffney, developed the theory that the most exhilarating action in baseball transpired when a player decided to stretch his triple into an inside-the-park home run. The second most exciting play developed when a runner calculated he could turn a safe double into a triple. Assured that fans would agree with him, Gaffney built his dream park with more resemblance to an airstrip than a baseball field. In the newly built Braves Field, the fence in left field was 430 ft. from home, and just right of straight-away center the fence was an impossible 550 ft. from the plate.

The Boston decision-makers soon realized they needed a center fielder who could cover the vast wide-open spaces of Braves Field and give the club a home-field advantage. The man they selected was the “rabbit” from the Ozarks named Ray Powell. Powell arrived in Boston in 1917 with great expectations and much fanfare. The local press proudly announced that the Braves had signed the “Ty Cobb of the West.”

By the 1920 season, Powell had become the Braves' regular center fielder, although his batting average for those seasons was .244, and he led the league in strikeouts in 1919. The Braves were okay with that as long as he patrolled the far reaches of Braves Field. In the game of May 1, 1920, Rabbit Powell batted leadoff, and he had the best view in the ballpark for the longest game in major league history.

It had rained most of the morning in Boston, but by game time, only a slight drizzle remained as Boston’s Joe Oeschger took the mound to face his rival, Leon Cadore. The pair had opposed each other for 11 innings ten days earlier in a 1-0 Brooklyn win.

On May 1, Brooklyn got a run in the fifth inning on a single, a ground ball that advanced the runner, and another single. Boston’s lone run came in the sixth, on a triple and a single. After eight innings of the historic game, the teams were tied at one. In the bottom of the ninth, it looked like Powell’s baserunning skills had won the game. With one out and runners at second and third Powell walked to load the bases. Was it an intentional walk? Baseball Reference.com does not indicate that it was.

When the next batter rapped a sharp ground ball to second, the speedy Powell avoided the tag and the winning run scored on the putout at first. Not so fast. Umpire Eugene Hart ruled that Powell had detoured out of the baseline to avoid the tag. Officially nine innings ended on a 4-3 double play.

The game continued for another 17 innings. The Robins got a runner to third in the 17th, but this time Boston’s double play ended the threat. Generally, both teams went down quietly as the cool damp day moved toward a chilly twilight. Finally, or prematurely if you believed he had a steak dinner planned, home plate umpire Bill McCormick ultimately ended the misery. In what would seem absurd in today’s game, both Cadore and Oeschger were still on the mound in the 26th inning!

In another amazing sign of the times, the 26-inning affair lasted just three hours and 50 minutes. In 2021, the AVERAGE nine-inning game was only 39 minutes shorter.

With what the press called a strong wind blowing in off the Charles River, Rabbit Powell justified his role in the longest game in major league history. He had eight putouts in center field. Powell made 11 plate appearances in the game. He singled once, walked three times, and had a sacrifice bunt. Perhaps indicative of his hitting prowess in those days, his official one-for-seven day at bat raised his batting average from .139 to .140.

Ray Powell’s complete biography can be found in Backroads and Ballplayers p.72

Hogwash

Observations:

Peyton Stovall is a difference-maker. Who hits .320+ after an extended injury?

Freshman Nolan Souza’s OPS is 1.210!

Kendall Diggs has a special strike zone awareness, but he hits behind in the count a lot.

Brady Tygart has had a lot of work pitching out of trouble, mostly created by command issues, BUT he is almost unhittable ahead in the count.

Where does Peyton Holt play? He is hitting .348?

Wehiwa Aloy looks like a major-league player. (or maybe Jalen Battles)

Will McEntire is just unflappable. His journey from obscurity to becoming the go-to guy is inspirational.

The TV guys mentioned twice that 10,000 fans can be quiet until awakened, but 30,000 in a weekend is amazing. In so many ways, baseball is still “Arkansas’ Game.”

Share an observation?

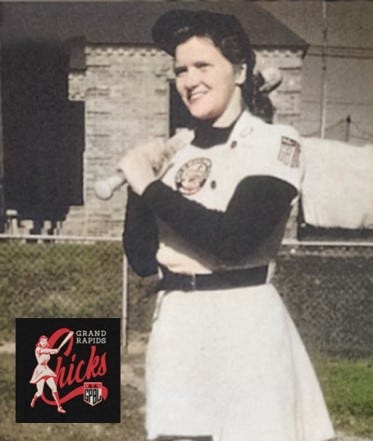

March is Girls and Women in Sports Month - I wrote a tribute to Mid Earp in Only in Arkansas.

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/