Backroads and Ballplayers #45

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Our Friend Tom, Lost Stories: Joe & George and the Rogers Brothers

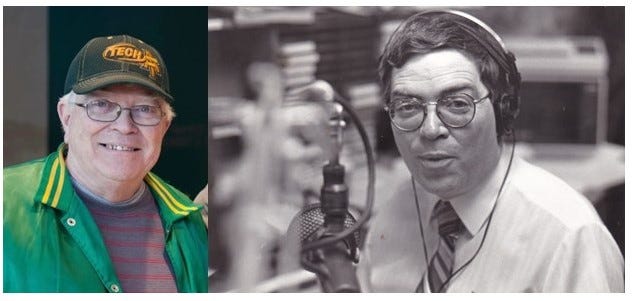

Tom

We lost Tom Kamerling last week in a tragic accident. I cannot begin to express what this incredible gentleman meant to my community and my family. He played our favorite songs, warned us that there was a hook echo over Lake Dardanelle, and seemed to be at every ball game and public event in town.

Everyone knew Tom and his distinctive professional voice filled our days and narrated our story. Tom Kamerling was indeed the “soundtrack of our lives.” Most importantly, he was my friend.

Lost Stories - The Rogers Brothers - A Preacher, a Mayor, and a Pearl Digger

Two weeks ago I had lunch in Conway with a group of retired professors from the University of Central Arkansas. In one of those chance encounters that seems to happen only in Arkansas, the gentleman to my right introduced himself as Rusty Rogers, and continued, “My grandfather was a baseball guy before he became a minister. His name was W. F. Rogers and he grew up on a farm in Pope County, Arkansas.”

Coincidently, Rogers' grandfather was part of a family of three brothers who became my first baseball history project almost ten years ago. William Fenna, Brown, and Henry Rogers were the oldest sons of a single-parent father who raised a family of six on an extensive farming operation near Pottsville. Despite needing his sons to work on the family farm, Madison Rogers valued higher education more than extra help in the fields.

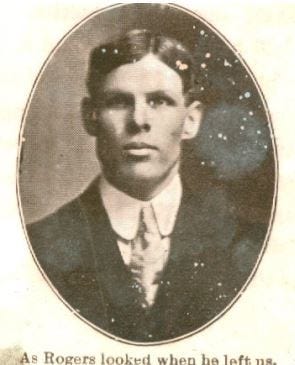

William Fenna Rogers

The oldest Rogers son, William Fenna Rogers, remained on the farm for a few years before enrolling at Ouachita Baptist College at age 22. Fenna Rogers arrived at OBC in 1903 to pursue a degree in religion and immediately became the most accomplished athlete at Ouachita. The college yearbook, The Ouachitonian, describes him as the “Champion pitcher of the south,” while expressing admiration for Rogers’ strong religious conviction that precluded him from Sunday baseball.

After graduation, Fenna Rogers went on to play three seasons of minor league baseball. In 1909, he won 19 games and lost five for the Class A Columbus Senators in the American Association, one step below the big leagues. Despite a clear path to major league baseball, Rogers’ lifetime goals were unaffected by his baseball success. With the extra money he earned playing minor league baseball, he enrolled at Princeton University to earn his doctorate in divinity.

Dr. William Fenna Rogers would serve as pastor of churches in small towns throughout Arkansas, including a lengthy service at the First Presbyterian Church of Clarksville, Arkansas. Rusty Rogers recalled that his grandfathers loved small-town life and preferred the close-knit community of a smaller church. Dr. Fenna Rogers died in Warren, Arkansas in 1982.

Edward Brown Rogers

In 2011, Tom Priddy, a journalist from Spartanburg, South Carolina, Googled his grandfather’s name. The family story that his grandfather, Edward Brown Rogers, had been an outstanding professional baseball player is a common tale, similarly told, in many families. More often than not, the family legend is disappointingly disproved by the easy availability of accurate online resources. To Priddy’s surprise, the family stories did not tell the complete story of a talented pitcher bound for the major leagues.

Brown Rogers originally joined his brother at Ouachita. He later transferred to Louisiana Industrial Institute (now Louisiana Tech) and played the remainder of his college baseball there. After college, Brown Rogers joined his older brother Fenna in his first year of minor league baseball. Fenna Rogers, known in baseball as “Parson Rogers,” coaxed his younger brother to Washington, Pennsylvania, where the brothers spent the summer of 1907 pitching in the Pennsylvania-Ohio-Maryland League.

Brown Rogers was a talented pitcher who had success at every minor-league level. He pitched more than 1,000 innings, and, with some seasons missing from his career records, he posted at least 80 professional pitching victories. At 6’5” and 180 pounds, Rogers’ attention-getting appearance led to sports page hyperbole and descriptive nicknames. One newspaper called him the “human hairpin.” The Atlanta Journal claimed he was the only man in pro baseball who could step from home plate to first base with one stride.

Did Brown Rogers have what it took in the early 20th century to become a major league pitcher? Evidence suggests that he had a good chance of reaching that level had he remained in the game.

Rogers gave up professional baseball in 1913, finished law school, and became an attorney and businessman in Russellville, Arkansas. In 1920 he was elected the city’s mayor. Brown Rogers died unexpectedly in Russellville, Arkansas, on August 8, 1932. He was 48 years old.

Henry Nelson Rogers

The third brother, Henry Rogers, stayed in Arkansas and enrolled at the Arkansas Military Academy, a prep school in Little Rock. Henry Rogers was an outstanding performer in several sports and played fullback for the school in 1907 when AMA defeated Russellville High School 62–0.

After leaving Arkansas Military Academy, Rogers spent the summer of 1909 as an outfielder for the Newport Pearl Diggers in the Class D Northeast Arkansas League. He hit .337 for the Pearl Diggers, the highest batting average on the team. The 1909 season was his first and only year of professional baseball.

On September 21, 1909, the Russellville Arkansas High School Athletic Committee met to make decisions about the upcoming Russellville High School football season. After electing officers, the committee chose 22-year-old Henry Rogers of Pottsville as coach of their high school team, then known as the Athletics. Russellville apparently recalled Rogers’ performance in the game two years earlier when, as a high school player, he had been instrumental in a drubbing of the Russellville High School squad.

Henry Rogers won four and lost three as the football coach of the Russellville High School Athletics in 1909. According to Mickey Duvall, Historian of Russellville Cyclone Football, Henry Rogers coached the Athletics for four seasons and posted a cumulative record of 10–12–3.

As Tom Priddy discovered, family stories of ancestors’ accomplishments are not always embellished. Although none of the Rogers brothers played major league baseball, their story of athletic achievement and personal success is one of the most significant and inspiring family biographies of those early days in the Arkansas River Valley.

In December 2008, Ouachita Baptist University announced an $800,000 gift from the Fenna Rogers Foundation, headed by Rogers’ son, to establish a new facility for the Ouachita speech and communications department in honor of Fenna Rogers.

Lost Stories - George and Joe Attain Lasting Fame

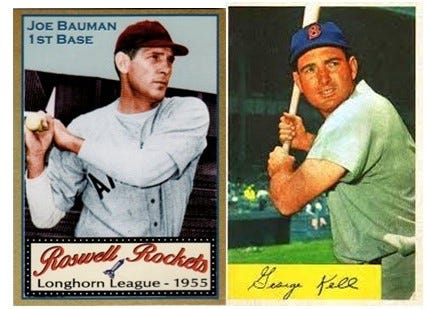

In the summer of 1941, the Newport, Arkansas, Dodgers of the Northeast Arkansas League had two teenagers playing their first full season. George Kell, from nearby Swifton, had been signed the previous summer and played in a forgettable 48 games with Newport. Kell hit .160 for the 1940 season and was not quite ready for the Northeast Arkansas League. By his second season, he was 18 years old, and that year must have made an amazing difference. He would lead the Dodgers in most offensive categories.

The Newport Dodgers assigned Kell a roommate from Welch, Oklahoma, a 19-year-old named Joe Bauman. Both Kell and Bauman would go from the Northeast Arkansas League to lasting baseball fame. Kell, as a Hall of Fame third baseman and broadcaster, Bauman, as a filling station operator, semi-pro star, and a legend in Roswell, New Mexico.

Joe Willis Bauman was born on April 16, 1922, in the small town of Welch, Oklahoma. Welch is located in the northeast corner of the state near Commerce, where another baseball player made a name for himself a few years after Joe had left Welch for Oklahoma City.

After signing right out of high school, Joe Bauman spent the first week of the 1941 season with the Little Rock Travelers. He had played in three games and gone hitless in 10 plate appearances before joining Kell in Newport. The Newport club was an affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers and managed by Merle Settlemire, a 38-year-old minor league veteran. Settlemire was assisted by Brooklyn scout Tom Greenwade.

Greenwade had been pitching in various semi-pro and independent leagues since the early 1920s, and, at age 36, his playing days were limited. However, his success as a scout was just beginning. The signing of future Hall-of-Famer George Kell marked the onset of a distinguished career, highlighted in 1949 by the signing of another future Hall of Famer by the name of Mickey Mantle.

The Newport Dodgers of 1941 dominated the Northeast Arkansas League. Although the club won both halves of the league schedule, only Kell, Greenwade, and, of course, Big Joe Bauman, achieved lasting baseball fame. While his roommate, George Kell, made the jump from the Northeast Arkansas League to baseball stardom quickly, Bauman took a detour.

Shortly after the 1941 season ended, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Bauman spent the next four years working in a defense plant and serving as a coach for the Naval Air Station in Norman, Oklahoma. With many pro baseball players in the military, the high-level competition improved Bauman’s skills quickly. He came out of WWII as a much better player than when he entered. At age 24, he still had time to start a baseball career.

Bauman found a spot in the Boston Braves organization in 1946, playing for the Amarillo Gold Sox in the West Texas-New Mexico League. The much-improved slugger, who had hit just three home runs in his initial pro season in Arkansas, batted .301 and hit a league-leading 48 home runs. In 1947, Bauman raised his batting average to .350 with 38 home runs. He was obviously not the same guy who hit .215 for the Newport Dodgers, but while his ex-roommate, George Kell was winning a batting title in 1949, Joe Bauman “retired.”

After a disastrous promotion to a Class A team in Hartford, Connecticut in 1948, Big Joe gave up his brief pro-baseball dream, went home to Oklahoma, and opened a Texaco station on Route 66. He settled in back home pumping gas and fixing flats at the station while playing with a semi-pro team at Elk City, Oklahoma. The Elk City Elks won the Oklahoma state semi-pro title in 1949, 1950, and 1951, earning Joe some renewed attention. A chance for a fresh start and an upgraded filling station lured Joe back into pro baseball in 1952.

Thus began one of the most implausible four-year hitting performances in the history of professional baseball. Playing in New Mexico, first with Artesia and then Roswell, Bauman thrived in the thin air and home run-friendly ballparks of the Longhorn League—Big Joe averaged 55 home runs a season from 1952 to 1955.

The most astounding of those seasons was 1954, his first year with the Roswell Rockets. He entered the last two weeks of the season with 55 home runs, 14 short of the minor league record. With the aid of a four-homer night on August 31, Bauman finished the year with 72 home runs, a minor league mark that still stands today. (Barry Bonds holds the almost ignored professional single-season record with 73 home runs in 2001.) Big Joe’s stats for 1954 were spectacular—72 home runs, 224 RBIs, and a batting average of .400.

Bauman played one more full season and part of another after an off-season injury hobbled him in 1956. He continued to run his Texaco station in Roswell and later became the sales manager in a beer distribution business. Joe Bauman Stadium in Roswell bears his name, as does the annual award given each year to the minor league home run leader. Joe Bauman died in Roswell in 2005. In 2021, the Joe Bauman Award was won by M. J. Melendez of the Northwest Arkansas Naturals.

March is Girls and Women in Sports Month - I wrote a tribute to Mid Earp in Only in Arkansas.

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Jim: This column is a classic, a wonderfully rich assemblage of unusual baseball tales. They're all great, but the Baumann rang some special bells for me. My sandlot and high school battery mate in Connecticut. was John Forline, later a Dartmouth College hurler whose brother played for years in the minors and for a spell with and/or against Baumann. John peppered me with stories about the sizable first sacker. Mike played many seasons in Reidsvlle, North Carolina, where John would spend many a week in many a summer traveling with the Class B club. Fine experiences for John, later an M.D. who--

with his only child, a daughter--DROWNED in the Nile in Egypt after losing his wife to cancer just months earlier. A convoluted story, admittedly, but coming to me only because of the slugger. Thanks tons again!