Backroads and Ballplayers #44

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia, Lost Stories, and some Hogwash

Caleb Hardwick and the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia

One of my most asked questions goes something like this… “Where do I find information on my grandpa who played baseball in Arkansas in the 20th century?” The answer is the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

How reasonable is this? A 15-year-old guy in Haskell, Arkansas, wakes up one day and decides to create a baseball research project. He is not interested in writing an essay for sophomore English. He has no enthusiasm for publishing a book and he isn’t inclined to submit an article to the local newspaper. How about an encyclopedia? Certainly, there is a place for an Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia. To make this ambitious project even more complex, a 21st-century encyclopedia would need to be web-based. Okay, now start researching, writing, and publishing. Sounds daunting…yes, impossible maybe, but Caleb Hardwick did it in high school.

Not only did the teenager succeed in creating his project, but he also produced the most significant contribution to Arkansas baseball history ever published. He does not simply write FOR the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia, Caleb Hardwick IS the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

Lost story - Ervin Moore Jr.

On June 16, 1957, one of Arkansas’ most promising prospects signed with the Kansas City Athletics. The event was given a few lines below the fold on the sports page of the Arkansas Democrat. It was the first time the name Ervin Moore Jr. of Roland, Arkansas, had appeared in his hometown newspaper. As he moved up through the As’ organization, it was hard to find his progress in Arkansas baseball stories and when a career-ending injury prematurely terminated his major-league dream, his return to Roland went unnoticed.

Moore was a left-handed pitcher with a big-league fastball and a knee-buckling curve. Because of the major league success of Black players like Don Newcombe, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron, scouts were taking notice of African American pitchers like Moore. Although he was not getting regular attention in the sports pages like his white contemporaries, the Kansas City As found Ervin Moore pitching against men’s teams in Roland, Arkansas. His story is one of Arkansas baseball’s “lost stories.” Thanks to Dr. Tom DeBlack and Dennis Moore, I am honored to share Ervin Moore’s story.

After a ten-game trial at Grand Island, Nebraska, in the late summer of 1957, 21-year-old Moore was assigned to Plainview, Texas, in the Sophomore League in 1958. In his first full season in pro baseball, Moore was his team’s best pitcher. Unlike his obscure days back home, Moore was getting noticed regularly in the Texas press, “Crafty Ervin Moore of Plainview boasts an admirable earned run average and has fanned 39 to top the league in both departments” -Abilene Reporter-News. Moore was the Plainview Athletics’ season leader in pitching wins, innings pitched, and strikeouts.

Moore split the 1959 season between Olean, New York, and Pocatello, Idaho. He started 16 games and was used as a relief pitcher in 15 more, posting a record of nine wins and seven losses. Moore was moving steadily up the minor league ladder. His next promotion would send him up to the West Coast.

Moore opened the 1960 season with a promotion to Class C Visalia in the California League. At age 23, it looked like he was destined to reach the majors with another solid minor league season. Moore had pitched more than 300 professional innings, and although 1959 was a very good year, something was wrong.

Visala used him as a late-inning relief guy, but a peculiar back problem limited his effectiveness. Moore was not the same pitcher that had looked like a big-league prospect in his first three seasons. The diagnosis of his injury was not encouraging. In fact, it was devastating. The sports medicine of the 1960s reported the pinched nerve in his back left him with two difficult choices, continue to pitch and risk paralysis, or go home.

In mid-season 1960, Ervin Moore Jr. retired from pro baseball at age 23. He returned to Roland, took a full-time job, and settled into what he assumed was a life without baseball. His big league dream was gone, but his pitching days were not over. As is often the case with mysterious back injuries, Ervin Moore got well.

The story of a big league prospect once headed for Kansas City became the tale of a semi-pro legend in the obscure baseball world of the last vestiges of town-team baseball. Part Satchel Paige and part Davy Crockett, Ervin Moore hit birds with rocks, blew fastballs by the best hitters in Sunday afternoon baseball, and possessed the guile earned over four pro seasons.

Moore’s catcher, a chatterbox and expert trash talker called “Bowie,” provided the context. Bowie made sure the opposition knew he had to add a powder puff to his mitt to handle Moore’s fastball and he provided occasional “warnings” in tough situations. “He is really mad out there. I sure hope he don’t hit you! He might kill you!”

The 1960s were the last years of Sunday afternoon town-team baseball. On some special Sundays, Ervin Moore’s Black Dodgers would play their arch-rivals the Little Rock Black Yankees. The ladies would swap family gossip under the shade trees, and Amelia and Allen Sims would set up in a barbeque stand. Sunday semi-pro baseball was the place to be and Ervin Moore Jr. was the star of the show.

By the early 1970s town baseball teams had become the “Joe’s Diner” of slow-pitch softball, and televised sports replaced Sundays at the baseball park. Ervin Moore finally gave up pitching and Arkansas lost a part of its baseball folklore.

Ervin Moore Jr. died in 1993. His baseball life and the lost stories of men like him are valuable chapters in Arkansas’ sports history. If you have a grandpa baseball story, let me know.

Lost story - Ray Caldwell, “Point Me Toward the Plate!”

In the pennant-winning year of 1920, the Little Rock Travelers drew 165,000 fans. After two fourth-place finishes and two consecutive last-place disasters, the hapless Travs lost 101 games and attendance fell to just over 50,000 in 1924. The free-fall cost the once popular Kid Elberfeld his job and initiated a roster purge that left only Rube Robinson safe from the locker cleanout.

The situation had become so desperate that the Travs proudly publicized the signing of a 37-year-old ex-major-leaguer named Ray Caldwell. In a bold headline, the Arkansas Gazette announced that the notorious pitcher and Mrs. Caldwell would join the Travelers immediately in Hot Springs.

Every fan with even casual baseball knowledge had heard of Ray Caldwell. He had won 134 big-league games and his lifetime ERA with the Yankees, Red Sox, and Indians was an excellent 3.22. Caldwell was famous by the standards of early 20th-century baseball fame, but most of his notoriety did not come from his pitching. The Gazette failed to mention that the 37-year-old veteran had numerous suspensions for a drinking problem, several mysterious unexcused absences and that he had been fined numerous times for “irregular behavior” and various off-the-field “escapades.”

His last years in the major leagues were with the Cleveland Indians, managed by former Travelers’ center fielder Tris Speaker. (Our friends at Grammarly remind me that this team should be called the Cleveland Indigenous Americans) Tris had developed a strategy that had saved Caldwell’s career and made him a 20-game winner in Cleveland. It seems that Speaker had not only allowed Caldwell to drink excessively, but he had also mandated it. The only stipulation was that he get drunk only the evening after the game. He could take the next day off to recuperate, before returning for three days that he was sober enough to pitch. Caldwell went 20 and 10 in 1920, but by 1921, even the “Speaker plan” did not make Ray Caldwell worth the disciplinary baggage that accompanied him.

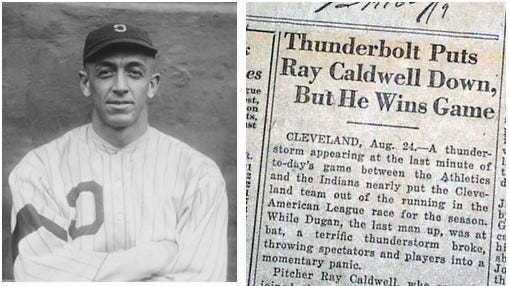

The tales of Caldwell’s indiscretions followed him to the minor leagues where he had spent the four years before coming to Little Rock, but his big-league career and his sordid story of misbehavior were not his most significant claim to fame. Ray Caldwell’s lasting notoriety would be earned on one hot summer day in 1919.

“Give me the dang ball and point me toward the plate!”

The date was August 24, 1919, and Speaker had just obtained the veteran pitcher’s services for some help during the last month of the pennant drive. Many thought it was the last chance for Caldwell to overcome his reputation and remain in the big leagues. There was a lot at stake, but a pennant race and a pitcher trying to salvage his career did not turn out to be the big story.

Although it was an unusually hot humid afternoon, the weatherman had predicted some showers would arrive and cool the late summer air. Perhaps a thunderstorm would be part of the weather change.

Caldwell was masterful. He looked every bit like the great pitcher he had been early in his career, and the Cleveland fans were solidly behind him as he entered the top of the ninth clinging to a 2–1 lead. The sky had darkened ominously in the last few minutes and Caldwell worked fast. The wily veteran got two quick popouts as a fast-moving storm quickly engulfed the stadium.

Suddenly a blinding flash lit up the dark afternoon and a lightning bolt drilled down into League Park, accompanied by a deafening clap of thunder. Patrons ran for cover, and players on the field dove face-down where they were. Witnesses claimed to have seen shards of visible electric current spring up in various spots on the field. Horror gripped what was left of the 20,000 in attendance, as they gazed down at the players lying motionless on the playing field.

Gradually, one by one, the players took stock of themselves and clamored to their feet. All except pitcher Ray Caldwell who remained face down on the mound. Cautious teammates approached their pitcher, expecting the worst.

Finally, Caldwell stirred, sat up, and clamored to his feet. All present agreed that small trails of smoke rose from a black spot on his chest, but the pitcher refused to leave the mound. “Ray just got up, shook his head a couple of times, like a steer that has been kissed by a locomotive, and barked at Ray Chapman…Give me that danged ball and turn me toward the plate.” —Frank Hyde, The Post-Journal

When all had sufficiently recovered, Jumpin’ Joe Dugan strolled tentatively to the plate with a drizzle still falling. Although most of those attending had headed for the exits or were huddled under the bleachers, thousands would later claim that they saw Dugan ground out to end the game.

The story has lasted over 100 years, it has been retold and rewritten hundreds of times and remains one of those tales that only seem to happen in baseball. Ray Chapman had been struck by lightning and lived to complete the game.

Chapman became a 20-game winner the next year, but by the time he came to Little Rock he was 37 years old, and his best years were certainly behind him. He remained in Little Rock for parts of three seasons, winning 35 games while losing 54.

Caldwell hung on in baseball until age 45. America was in the throes of the Great Depression, and he had to make a living. He died of cancer in Salamanca, New York on August 19, 1967. His day in a thunderstorm is one of baseball’s “lost stories.”

Note: If you like these stories, I have two books in print with more than 100 like this. See the link at the end of this post.

Hogwash

I think the Razorbacks played a pretty good team this past weekend. Murray State will win a bunch of games. They have 31 juniors and seniors and the pitchers they used Sunday looked solid.

It is hard not to get excited about this Razorback team. Once again, the three starters dominated. Hagen Smith, Brady Tygart, and Mason Molina combined for 16 innings, six hits, and 32 strikeouts. Will McEntire, Coach Hobbs’ “hybrid reliever,” pitched his usual five-plus innings and also gave up one run. Like his starting teammates his lone earned run was a homer.

If there is a concern, the lineup is a work in progress. I thought Nolan Souza, Jayson Jones, and Ross Lovich had good at-bats in the series and they may get a chance to play more. It is possible, perhaps likely, that Coach Van Horn will start the SEC gauntlet, “building an airplane in the air.”

If this is a Razorback squad that turns out to be a team with exceptional pitching and inconsistent hitting, it will not be the first. Maybe you recall 2013. Brian Anderson had a really good year. He hit .325 for the season, but .371 in conference games. The rest of the position players combined to hit about .250, 11th in the SEC.

That pitching staff was not only the class of the SEC, they were the best anywhere. They had college baseball’s best ERA by half a run per game. In SEC games, Ryne Stanek’s ERA was .097, Barrett Aston’s was 2.14 vs. SEC foes, and Sunday starter Randall Fant posted a 2.23.

Future major leaguer Jalen Beeks pitched in 14 SEC games, with a 1.83 ERA. SEC hitters batted .156 against him. Colby Suggs recorded saves in 10 SEC games. His ERA against conference foes was .75. SEC hitters hit .167 against Suggs.

The 2013 Hogs finished 18-11 in the SEC, and second in the West, but stumbled into the regional losers bracket against Bryant. They were eventually eliminated from that regional by Kansas State.

I think this team has a little more pop than that team, and if Peyton Stovall comes back for most of the SEC games this year’s team will probably be okay at the plate. Once again, it is early. Hold on to your hat.

Review of 2013 Season 2014 Media Guide

What do you think?

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/

Another good read, Jim!

Bob Reising