Backroads and Ballplayers #43

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Book Talks, Ks in Texas, and Finding Lost Stories

Joe and I are Making Book Talks!

Thursday I hosted an informal group at the Pope County Library’s continuing “Arkansas Stories” series. I love this format. I enjoy hearing your stories more than telling mine. Please share your “grandpa stories.”

I see my favorite writer is also doing some free Thursday book talks. I like Joe Posnanski’s book Why We Love Baseball very much, but his book The Baseball 100 is my all-time favorite. The only thing similar about our work is that we both write essay-style chapters that can be read independently in one sitting. My wife calls them bathroom books, but I like “one cup of coffee stories” much better.

By the way, it seemed like everyone at my Pope County Library event was a Cardinals fan. To get the best insight into the Redbirds’ ups and downs, I highly recommend my friend Cardinal70’s substack column/blog. Link

Lost Stories

I loved writing about Brooks Robinson, George Kell, and Dizzy Dean, but comprehensive biographies of Hall of Famers are easy to find. Six men who were born in Arkansas have a plaque in Cooperstown. Hundreds more Arkansas-born men and women lived rich, interesting, and often tragic baseball lives without fame or fortune. I call their lives “The Lost Stories.”

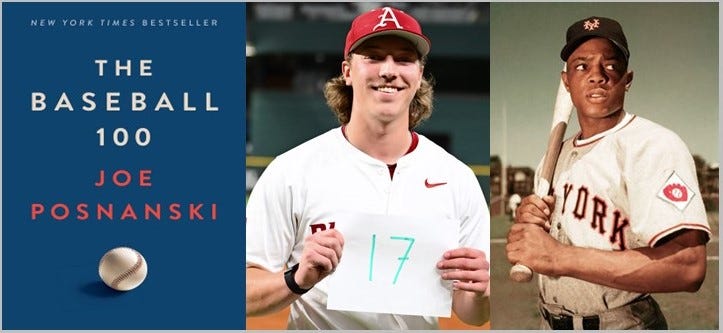

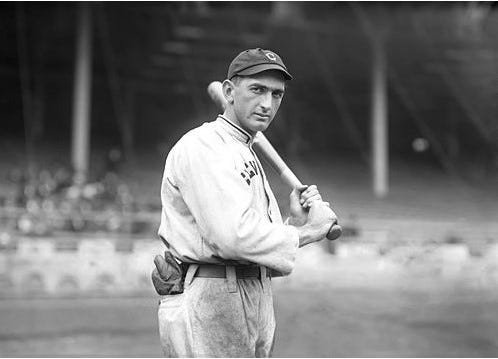

The Lost Story of April 6, 1920, Shoeless Joe in Little Rock

West End Park was the last stop for the Ninth Street Trolley Line. Little Rock’s most popular public transportation choice took streetcar passengers to 14th Street near the entrance to the park, and from there, it was a short stroll to the ballpark. The park was the home of the Little Rock Travelers, a lake, and a bicycle track. It was the most visited recreational option in early 20th-century Little Rock.

On April 6, 1920, more than 2,000 fans took that ride or walked to West End Park to see the hometown Travs play an exhibition game with the reigning American League Champions.

It was not unusual for major league teams to stop in minor league towns to play exhibition games on their way north to start the regular season. The Chicago White Sox played one of those games in Little Rock on that spring day. The fans attending had no reason to suspect this exhibition game against a team that played in the last World Series was anything other than a chance to see a big-league team in action. In hindsight, the game would be a historic event in Travelers history.

These White Sox were the American League Champions. They were also the team that had lost the World Series six months earlier under suspicion that they consorted with gamblers to throw the series. That day, against the Travs, the big-league stars gave the crowd what they came to see. Shoeless Joe Jackson hit a triple in the first inning, Buck Weaver had three hits in the game, and Happy Felsch had four hits, including a three-bagger. Swede Risberg, a promising 25-year-old, dazzled the Little Rock crowd at shortstop. The White Sox appropriately defeated the home team 10–5.

Jackson, Weaver, Felsch, and Risberg were playing their last season in pro baseball. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis would permanently ban the four in August 1921, along with pitchers Lefty Williams and Ed Cicotte, first baseman Chick Gandil, and infielder Fred McMullen.

No one in Little Rock that April day in 1920 had the insight to imagine they were watching the most infamous team in baseball history. Although researchers examining the same 100-year-old information disagree on the guilt of some of the eight players being banned and the group was found not guilty in court, Landis’ final decision ended the careers of the men forever known as the “Chicago Black Sox.”

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ballgame; no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame; no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing games are planned and discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball. –Kenesaw Mountain Landis, August 21, 1921

Chasing Lost Stories in Conway - Look for these lost stories beginning next week.

My friend Dr. Tom DeBlack invited me to lunch on Monday. Tom is a retired history professor from Arkansas Tech who literally wrote the book on ATU, among his many projects. (A Century Forward: The Centennial History of Arkansas Tech University 2016)

Tom had a few people he wanted me to meet. It turned out to be one of the most memorable days since I began my Arkansas baseball history project about ten years ago. The stories below all came from Monday’s trip to Conway. I look forward to sharing them beginning next week,

Ervin Moore (Dennis Moore)

Dennis Moore has spent his life in law enforcement. His father is one of those lost stories.

Sunday, June 16, 1957, the Arkansas Democrat ran a small story three pages deep in the Sunday sports page that announced that Ervin Moore Jr. of Roland, Arkansas had signed with the Kansas City Athletics. It was the first time the Little Rock newspaper had mentioned Moore on its sports page. Ervin Moore Jr. was African American, but ten seasons after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier in big league baseball, young Black men were still playing in the shadows of America’s Pastime.

The intriguing chronicle of Ervin Moore’s journey up through the Kansas City minor league system and the sudden end to his major league dream is not uncommon. Of the thousands of young men from Arkansas who sign a minor league contract, only 165 have reached the big leagues.

Look for the “Lost Story” of Ervin Moore

The Rogers Brothers (Rusty Rogers)

Rusty Rogers and the Rogers Brothers of Pope County

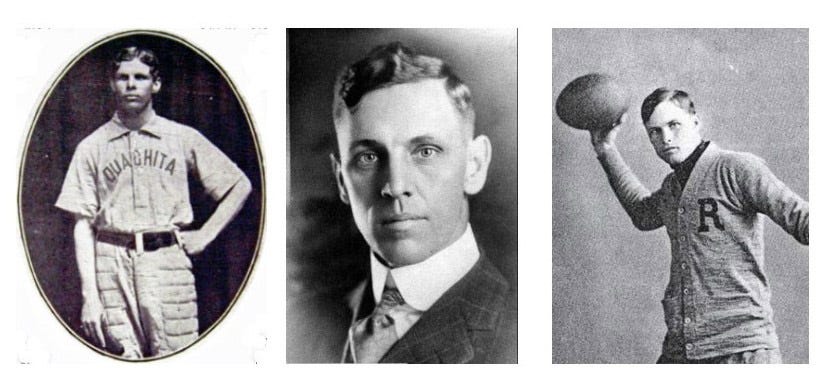

In 2011, a writer in South Carolina googled his grandfather. The story that Tom Priddy’s grandfather had been an outstanding pro baseball player was one of those family baseball stories that often turn out to be somewhat embellished in the retelling. That was not the case with Tom’s grandfather. Not only was he an outstanding player, but he was one of three brothers from Pottsville, Arkansas, who chose to give up a potential major league career for lives of service.

Monday at lunch I met Rusty Rogers, a retired University of Central Arkansas professor. Rusty Rogers’ grandfather was William Fenna Rogers, the oldest of the Rogers brothers. A coming “Lost Story” will feature Fenna, Brown, and Henry Rogers.

Willie Mays in Little Rock

Dr. Roy Whitehead Jr. and October 10, 1955

Two weeks ago I received an email from a baseball historian in New York who was researching a barnstorming team of Black major leaguers who toured the country immediately after the 1955 World Series.

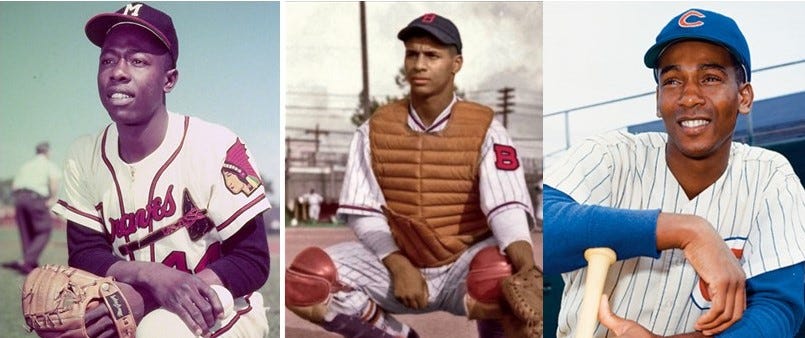

On October 10, 1955, the Don Newcombe All-Stars played the Negro League All-Stars at Travelers Field in Little Rock. Less than 3,000 saw some of the iconic Black stars in the history of baseball. The team included Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Roy Campanella, Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Jim Gilliam.

At Monday’s lunch, I mentioned that I was trying to find information about that game. Dr. Roy Whitehead Jr, a retired business law professor, calmly announced, “I was there.” Roy was a 19-year-old college freshman from Arkansas Tech when he and some friends drove to Little Rock to see the exhibition game.

A “Lost Story” coming soon - October 10, 1955.

Hogwash

Weekend in Texas, and an RPI Warning!

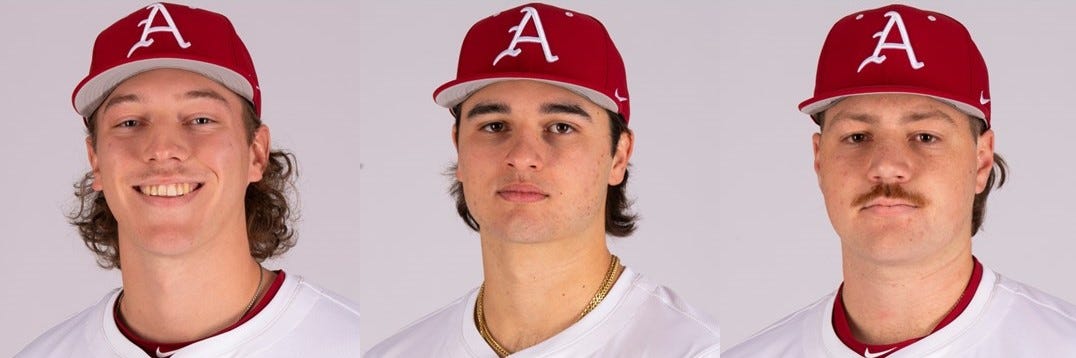

The Razorbacks won two of three in Arlington, Texas, over the weekend with three consecutive starting pitching performances that make the usual adjectives inadequate. Seventeen innings pitched, six hits, no earned runs, and 33 strikeouts from the starting pitchers were certainly encouraging, but the defense was shaky, runs were scarce, and the team batting average for the week-end was under .200. What does all that mean? It is going to be fun, but there are going to be some nail-biters. The SEC is excruciating.

I am baffled (sometimes frustrated) by the College Baseball RPI. It is not something to follow early in the season, given the small sample and the calculus involved behind the scenes. Despite this advice, I check the frustrating “live” version almost every morning during the college baseball season. Sure enough, on Saturday morning after the thriller on Friday evening, the Hogs jumped 138 spots to number 6. Okay, that makes sense, they beat a top-ten team at a neutral site.

That 138-spot leap was almost 100 spots less than the move by those daemons of the diamond, the Binghamton Bobcats of the America East Conference. The AEC is the loop that gave us our new friends from the New Jersey Institute of Technology in 2021.

On Friday evening, The Bobcats hung on to beat NC Greensboro 8—5 to jump 236 spots into the top ten in RPI. Apparently, a win by the Bobcats or a victory over the Bobcats has a valuable mathematical value in the RPI at this point.

Friday’s win improved Binghamton’s 2024 record to 1—4. Houston was number one on Saturday morning, having beaten the Bobcats three times, Prairie View 27—1, and Saint John’s 12—6. Houston’s current strength of schedule was number 1 on Saturday. That makes perfect sense since four of their wins are over teams who haven’t practiced outside in about four months, but they did beat number 10 Binghamton three times.

Seriously following the RPI at this time of the year is a complete waste of time. I do it anyway. You have been warned. Link to live RPI

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/