Backroads and Ballplayers #42

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Meet Me at the Library, Girls and Women in Sports, College Baseball, and Black History Month

Last week was a big sports week.

A women’s basketball player was the lead story on ESPN, a historic event that appropriately occurred during Girls and Women in Sports Month. The Caitlin Clark headlines brought back some unforgettable events in my life.

College baseball season opened. I saw Arkansas Tech’s home opener in person, UCA vs. LSU on ESPN, and the Razorbacks on SEC+.

AND…February is Black History Month. The stories of Black Arkansans in baseball are among my all-time favorites. These biographies are usually obscure, sometimes heartwarming, and often tragic. I will share some of them later in this post.

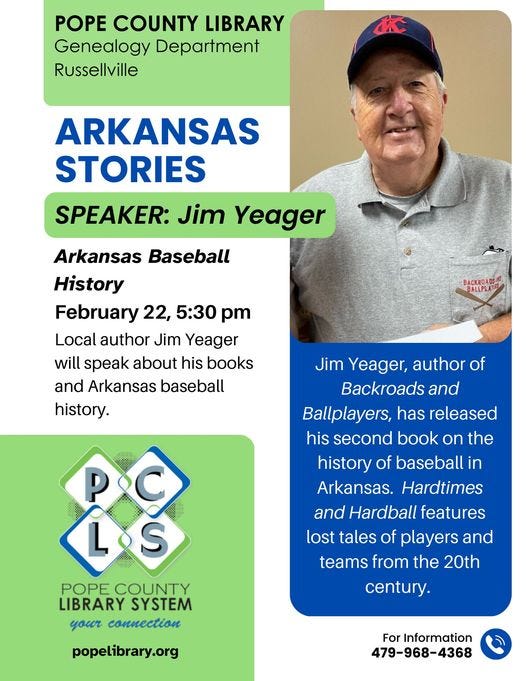

Let’s Talk Arkansas Baseball History at the Pope County Library

I hope some of you will be able to join me at the Pope County Library on Thursday, February 22. I always enjoy these events and I look forward to hearing your “grandpa stories.”

The Girl’s Game

On February 3, 1987, President Ronald Reagan signed Proclamation 5606 declaring February 4, 1987, as National Women in Sports Day. Thankfully, girls and women were finding their place in competitive sports long before a mandate from the president.

Thirty-seven years after the establishment of a date to recognize the importance of girls and women in sports, a college women’s basketball player is the number one national sports story of the week. So, before I write anything about baseball, I want to share a personal thought or two about what Clark’s notoriety means to girls and women’s sports. Her skills are beyond anything we have ever seen. I especially love the photos of Clark surrounded by young girls awestruck by a laudable hero.

As most of you know, in another life I coached high school girls and college womens basketball. At Arkansas Tech in the years immediately following Title IX, I was fortunate to have some talented young women who not only won championships but helped inspire a generation of young Arkansas girls to reach for the opportunities competitive sports could provide.

On a February Day in 1980, the university was hosting students for an event they called “Time Out for Tech.” We moved a scheduled evening game to the afternoon to take advantage of the large number of high school seniors who were on campus. Over 1,000 fans attended the game and many were girls basketball players from around Arkansas.

Sherry Raney White, our All-American forward, had an outstanding game that afternoon. After about 15 minutes of after-game duties, I headed for my office where a crowd of high school girls were still in line for Sherry’s autograph. She kinda smiled and shrugged at a scene that she never expected. Like Sherry, I had never seen dozens of young girls waiting to get an autograph from a female athlete. Things were about to change.

Since Sherry Raney White, there have been many other young women who inspired Arkansas school girls to become college athletes. These women were the Caitlin Clarks of Arkansas on a smaller and more local stage. Clark’s accomplishments and those of other female athletes from Iowa to Arkansas are the catalyst for even more significant attention to girls and women in sports. I have a feeling the best is yet to come, thanks to women like Caitlin Clark and Sherry White.

College Baseball

As expected the Razorbacks’ starting pitching looked good, and Will McEntire was…well, Will McEntire. It is a long season and there are big questions to be answered, but it is going to be fun.

I switched back and forth on Saturday between the Hogs game and UCA at LSU. I realize there are no moral victories, but there were some encouraging things for the Bears in their four games in Baton Rouge, including that 2—0 loss to the Tigers on Saturday.

I lasted six cold innings at Arkansas Tech’s home opener on Tuesday. The Wonder Boys won that game vs. Pittsburgh State (KS) 10—6. Since then they have lost three close ones in Oklahoma. They are at home again Tuesday at 3:00 with temps in the high 60s. I will see you there.

UCA is at home Friday, Saturday, and Sunday vs. Southern Illinois

Ozarks is at Hendrix next Tuesday (Feb. 27, 5:00 PM)

Go see some college baseball.

Arkansas’ African American Baseball Heritage.

To plagiarize a line from Ken Burns, ”They played everywhere,” but their stories are often lamentably undocumented. These men of color from the first half of the 20th century played their games in the shadows of America’s Pastime. They played on long-forgotten town teams, on obscure minor league teams, and in a major league known as the Negro Leagues.

On June 1st, 1991, California Angels pitcher Fernando Valenzuela made a rehab start with the Midland Angels against the Arkansas Travelers at Ray Winder Field. Attendance was unofficially reported at about 12,000, including my wife, Susan, my two sons, and assorted friends.

In October 1955, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, and Don Newcombe played an exhibition game at Travelers Field (Travelers Field became Ray Winder Field in 1966). The game pitted a team of Black major leaguers against a team called the “Negro League All-Stars.” In the segregated world of 1950s Arkansas, just over 2,500 saw many of the greatest players of the 20th century play in Little Rock.

A few weeks ago I received an inquiry from a baseball writer in New York about that 1955 game. He was researching that barnstorming team of Black major leaguers for an upcoming book. I contacted my friends at the Robinson-Kell Chapter of SABR, but we could offer little information the researcher did not already have. I am excited about my new friend’s work and look forward to his book. Is there a chance any of you know anything about this game or another game that may have been played in Pine Bluff?

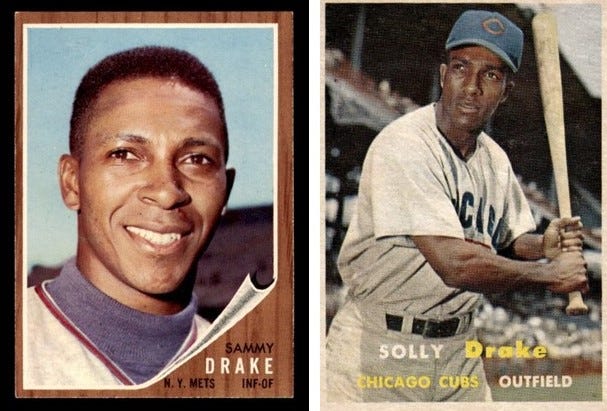

Solly and Sammy

About five months before Mays, Aaron and friends played an almost ignored game in Little Rock, the Arkansas Democrat ran the headline: “Brooks Robinson Signs Pact with Baltimore.” On May 29, 1955, under a picture of the recent high school graduate, the paper announced Robinson had agreed to his first contract with the Baltimore Orioles. The 18-year-old Little Rock High School product would report immediately.

The signing was the second such event in the last month in Little Rock. A month earlier, Samuel Harrison Drake had signed with the Cubs after impressing minor league manager Pepper Martin in a spring tryout.

There was no sports page photograph nor a bold headline for Drake’s signing. Sammy Drake was an African American and a graduate of Dunbar High School. He and Robinson never had an opportunity to compete against each other as baseball players growing up in Little Rock. Given the exemplary character of both young men, they would likely have been instant friends.

On the advice of his brother, Soloman, Sammy had played the summer after graduating from high school for an independent minor league team in Canada. After a good season in the Manitoba-Dakota League and an impressive minor league tryout, he was invited to spring training by the Cubs in 1955, he signed in April and was dispatched to Macon, Georgia, in the South Atlantic League (Sally League).

Solly Drake, four years older than his younger brother, had been in pro baseball since 1950, and he knew the difficult times that lay ahead for young Sammy. Although Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier for Black Americans in pro baseball, he had not broken the difficult discrimination that faced the pioneers who integrated professional baseball. A season in a more racially tolerant Mandak league would introduce the younger Drake to pro baseball in a more comfortable environment.

The Drake brothers grew up on Maryland Avenue in Little Rock, about a ten-minute walk from Lamar Porter Field but a world away from the busy summer leagues that thrived there in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Several of Brooks Robinson’s teammates candidly revealed that as youngsters they never heard of Solly and Sammy Drake.

Solly Drake played on men’s teams as a teen and immediately after graduation headed north to the Manitoba-Dakota League in Canada and North Dakota. The independent “Mandak” League attracted Negro Leaguers too old to follow Jackie Robinson’s route to pro baseball and young men looking for a start. Solly Drake was the latter. Although records are sparse, Solly Drake played several years for the Elmwood Giants in Winnipeg, Manitoba, before signing with the Cubs in 1951.

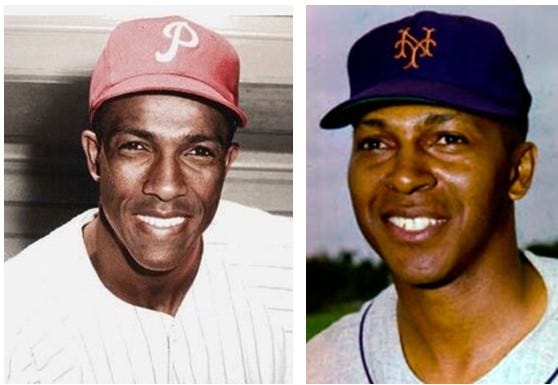

The elder Drake moved steadily through the Cubs minor league system, but a stint in the military, and two season-ending injuries delayed his big league debut until April 17, 1956. He got off to an encouraging start with nine hits in his first 24 at-bats, but a good April was followed by a dismal May. After seeing his batting average drop to .226, Drake was optioned in mid-May to St. Paul of the American Association where he immediately found his lost swing.

In 55 games in St. Paul, Solly hit .333 with nine home runs. By July 20, he was back with the Cubs. In his second shot with Chicago, he raised his batting average from .211 on July 20 to .256 when the 1956 season ended. He also added speed to a Cubs’ lineup not known for base running. In only 65 games and half the at-bats, Drake stole nine bases to tie Dee Fondy for the team lead.

Despite the good showing in the last half of the 1956 season, the Cubs decided to send Solly out to their Portland team in the Pacific Coast League in 1957 where he could play every day. Drake was just 26 years old, a good baserunner, and an excellent outfielder with the speed to track down drives that were headed for extra-base hits. The Cubs were not satisfied with him on the bench if he could become a good enough hitter to play regularly.

As expected, Drake flourished in the PCL. So much so, that the newly transplanted Los Angeles Dodgers made a deal to get him into their farm system. After hitting .290 and stealing 36 bases for Portland in the Cubs organization in 1957, he hit .302 for a pennant-winning Montreal Royals as a Dodger farm hand in 1958.

Although two excellent years in the PCL affirmed the Dodgers’ plan to promote Solly to the big leagues again in 1959, the soon-to-be World Series Champions were loaded with outfielders. After two months and only eight at-bats, Los Angeles sold Drake to Philadelphia on June 8, 1959.

The Phillies used Drake as an emergency outfielder and a pinch hitter for the remainder of the season. He never adapted to the one-at-bat role of a pinch hitter. Drake batted 25 times before getting his first hit and soon found himself used mostly as a defensive replacement or pinch runner. On September 27, 1959, he entered the game in the top of the ninth inning as a pinch runner. It was his last appearance in a big-league game.

Solly played two more minor league seasons before retiring after the 1961 season. He finished his career with a .232 batting average in 141 major league games. In Drake’s eight seasons in the minors, he posted a .288 batting average with 50 home runs and 95 stolen bases.

Following his older brother’s trail, Sammy Drake played a season in the Mandak League before he entered the real world of newly integrated minor league baseball. After signing with the Cubs in the spring of 1955, Sammy’s first assignment at Macon, Georgia, in the Sally League, was not simply an evaluation of his baseball skills. His introduction to pro baseball also tested Sammy’s resolve not to be driven from the game by the hostile social environment.

In an interview later in his career, Drake recalled: “We were called unspeakable, unprintable things simply because of the color of our skin. And these are my home fans.” It was especially difficult to find a place for the young Black players to eat. “There was this little hole-in-the-wall restaurant they had for us . . . I didn’t have any choice. And when I traveled, I had to stay on the bus while they would go and bring my food to me. That was very degrading.” Despite the difficult conditions, Sammy hit .251 for the 1955 season and led the team in stolen bases.

The Cubs assigned Drake to Lafayette, Louisiana, in the Class C Evangeline League to begin the 1956 season, but the segregation problems in the Evangeline League were an even bigger obstacle than in the Sally League the previous year. Local laws forbidding Blacks from participating in events with whites finally forced the Cubs to reassign Sammy to Burlington, Iowa.

Despite the turmoil that resulted in his transfer from Lafayette, Drake put together a pretty good year in 1956. He played for three clubs in the Cubs’ minor league system, batted .270 for the year, and stole 47 bases.

Military service interrupted Sammy’s climb up through the Cubs’ minor league system, but after missing 1957 and 1958, he started spring training with Class AA San Antonio in 1959. In early April, the Cubs’ decision-makers decided to return Drake to Burlington to begin the season. He played 77 games in Iowa before finishing the year back in San Antonio. Despite missing two seasons in the military, Drake batted a respectable .296 for the two teams.

He repeated the two-team routine in 1959, hitting .294 for a summer that saw Sammy play 88 games for San Antonio and 26 for Houston in the American Association. In 1960, the Cubs would once again invite Drake to spring training. He was 25 years old, and, with more than 2,000 minor league at-bats, it was now or never for Sammy Drake and the Cubs.

This time, after almost 500 minor league games, Sammy Drake made the Opening Day roster. A week into the season, he also made history. In the Cubs’ fifth game, on a Sunday afternoon in San Francisco, Sammy Drake entered the game as a pinch runner for first baseman Dick Gernert who had singled. His appearance marked the first time in major league history two African American brothers had reached the major leagues.

Sammy played in 15 games for the Cubs in 1960, another 13 in 1961, and 25 for the expansion New York Mets in 1962. In a total of 53 big-league games, he hit 11 singles and no extra-base hits in 72 at-bats. A knee injury after joining the Mets sidelined him for the 1963 season. Unable to regain his speed, Sammy retired for good in 1965 after two more minor league seasons.

The complete story of the Drake brothers can be found on page 362 of Hard Times and Hardball.

Complete versions of three of my previous stories about Arkansas’ African American baseball history can be found on my website. These will remain in the free area for the next month. Black History Month 2024

Book ordering information: Link

Have you missed some posts? Link - https://jyeager.substack.com/