Backroads and Ballplayers #31

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Jay Jaffe, 200 game winners, and a Marker on the Bike Trail

Just Thinking…How does the Hall of Fame evaluate the NEW starting pitcher?

From the end of the World Series until the pitchers and catchers report in February, baseball fans “enjoy” deep unemotional player evaluations(sure). Some of those contemplations are spent in roster-building for their team’s next pennant race, and, of course, there must be some careful and objective thinking about Hall of Fame candidates.

A guy named Jay Jaffe has tried to take the fun out of this process. His Jaffe WAR Score (JAWS) system attempts to “measure a player's Hall of Fame worthiness by comparing him to the players at his position who are already enshrined, using advanced metrics to account for the wide variations in offensive levels that have occurred throughout the game's history. The stated goal is to improve the Hall of Fame's standards, or at least to maintain them rather than erode them, by admitting players who are at least as good as the average Hall of Famer at the position, using a means via which longevity isn't the sole determinant of worthiness.” Baseball Reference.com

Come on Jay, you have Molina behind Mauer, Munson, Tenace, Freehan, Posey, Posada, and Jason Kendall! Really? Where does “likeability” figure in? What about “handling pitchers,” “stealing strikes,” and grit?

Just wait about ten years and try to put the math to Shohei Ohtani! He is currently 128th among right fielders, and he has yet to crack the top 500 starting pitchers in the all-time JAWS list. How do you measure a unicorn? By the way, Jaffe has taken a crack at this. Caution, this article is dangerous for those who have trouble balancing their checkbook. Link

Today’s starting pitchers are even more difficult to quantify, and there will be some advanced number-stretching for the Jaffe folks in the decades to come. The “new” starting pitcher will require some serious thought on who is a Hall-of-Fame-worthy starter.

Among today’s veteran starters, Justin Verlander (257 wins) ranks 19th all-time on the JAWS starting pitcher list. Clayton Kershaw ( 210 wins) is 20th. Only one non-Hall of Famer, Roger Clemens, ranks above these two sure things. Zack Greinke (225 wins) is 25th and Max Scherzer (214 wins) is 27th. Clemens and malcontent Curt Schilling are the only eligible pitchers who rank higher and are not in the Hall. Good job Mr. Jaffe, Greinke and Scherzer are in!

After these four pitchers who fit the Jaffe model, it gets very interesting. All of the above have won 200-plus games. Adam Wainwright finally won his 200th game on September 18. He does not look like a Hall of Famer in JAWS. (134th, behind, for example, Cliff Lee)

On the JAWS starting pitcher list, Cole Hamels is 83rd, behind Dave Steib, Bret Saberhagen, David Cone, Luis Tiant, KEVIN BROWN, and RICK REUSCHEL. His 163 wins is tops among active pitchers with fewer than 200 victories. Based on the math, he does not look like a Hall of Famer. Hamels is 39 years old.

This year’s AL Cy Young winner, Gerrit Cole, is 160th in the JAWS rankings among starting pitchers. He is behind Adam Wainwright, Schoolboy Rowe, Cliff Lee, and Lon Warneke. Cole is second in career wins among active pitchers with career total below 200 (145), and he is the youngest active pitcher with 100 wins. He is 32 years old, and his chances of getting high on the JAWS list are good, but he needs 100 more wins and climb over about 130 pitchers in JAWS to be a sure thing by today’s standards. Otherwise, he falls in with the Wainwright class of not-quite-HOF guys.

ANOTHER EXAMPLE: Aaron Nola is 30. He has 90 wins and a nice new contract. If Nola averages 15 wins a season for the length of his new seven-year, 172 million-dollar deal, he will not even catch Wainwright in career wins. He has yet to have a 15-win season. Nola is 261st all-time in career JAWS, behind the likes of Johnny Cueto, David Price, and Corey Kluber.

By the way, retiree C. C. Sabathia is also out there in his waiting period with Hall of Fame credentials. C. C. is a cautious yes. Retired Bartolo Colon also has Hall of Fame indicators, but he is a member of the Clemens-Bonds fraternity and despite his high likeability, Ole Bart is probably out.

I will have long ceased to write this column when we have another 300-game winner, but what about a 200-game winner or another pitcher in the top 50 JAWS rankings? Ken Burns is proud of saying “Baseball is a haunted game, where each player is measured by the ghosts of those who have gone before. Some of those measurements have to morph to evaluate the “new” starting pitcher.

Could Jelly be the guy?

Speaking of the Hall of Fame, I have been trying to find a baseball Hall of Fame inductee from Arkansas that might be selected in my lifetime. I have tried Torii Hunter, Lon Warneke, and Johnny Sain, but their chances do not look good.

Maybe I ride my bicycle by the birthplace of the next Cooperstown resident from Arkansas. Once again it is a stretch, but possible. About a half mile from my house, the new Russellville bike trail passes between the Russellville Middle School complex and Jonesboro Avenue. Jonesboro was called Orange Street when Floyd Gardner grew up here.

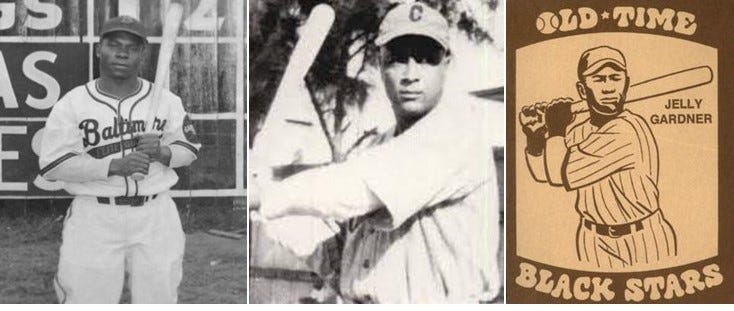

Who is Floyd Gardner? Floyd Gardner may have been the best baseball player from Russellville, Arkansas, in the early 1900s. He may even have been the best baseball player ever from a town in the Arkansas River Valley known for great baseball players. After all, he played at the highest level available to him. He starred in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Detroit, which are certainly major-league cities. During a 16-year career, Gardner played in almost every big city in America. He was a great outfielder, a flash on the bases, and a line-drive hitter who was often among the league leaders. Though Floyd Gardner was one of the outstanding players of his era and acclaimed by sportswriters throughout the country, he never played in a major league game. Not because he wasn’t good enough to get a shot, but because of the color of his skin.

Floyd Gardner was born in Russellville, Arkansas, in 1895. He spent the first 14 years of his life with his younger sister, Annie, and parents, Alex and Josie Gardner, on Orange Street in Russellville, which is now South Jonesboro Avenue. In 1910, he was sent to Arkansas Baptist College, a college/boarding high school for African-American students.

Arkansas Baptist was a good place for a young man with baseball aspirations. In Little Rock, Floyd was able to play baseball regularly, and by 1913, he was playing with an elite regional semi-pro team called the Hot Springs Giants. The Giants later combined with a team from Longview to become the Texas All-Stars.

When the Texas All-Stars headed north to play other semi-pro teams, Floyd Gardner attracted the attention of the leaders who were forming a new “major league.” This new professional baseball league would create a place to play for African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latino players who were excluded from the major leagues. This alternative major league would be forever known as the “Negro Major Leagues.” Negro League baseball would flourish until Jackie Robinson and others broke the major league color barrier 30 years later.

Like many young men of all races, World War I interrupted Floyd Gardner’s plans and his baseball career. By late 1918, he was overseas fighting for his country. The war also added a dramatic element to the Floyd Gardner story that fortunately had a happy ending. In the Arkansas Gazette on the morning of Dec. 27, 1918, Private Floyd Gardner of Russellville, Arkansas, was listed as Missing in Action, a designation that often indicates an unfortunate outcome. This time, the listing was resolved, and Floyd was soon back on duty. As slowly as news traveled in those days, one can only imagine the anguish Floyd’s Arkansas family went through. Gardner made it back from the Army in time to play a few games with the Detroit Stars in the summer of 1919 and then headed to Chicago, a city he would call home until his death.

Gardner was signed by the Chicago American Giants, and he became a star from the first day of Negro League baseball. Short, round, and jovial, Gardner was tagged with the nickname “Jelly Roll” by his teammates. Nicknames had a way of catching on in the early days of baseball in America, and Floyd “Jelly Roll” Gardner was never Floyd. He was simply called “Jelly.” He hit .319 in the first year of the Negro National League and became the darling of black sportswriters.

Jelly Gardner was always a good story. He loved to play the game, didn’t mind a good fight if that was necessary, and he made a manager’s life difficult. His Chicago American Giants were managed by the legendary Rube Foster. Foster would become a mentor to the young outfielder from Arkansas — or at least he tried to be.

One story retold about Jelly and Foster chronicled a game when Foster and Jelly’s American Giants were playing their cross-town rivals known simply as the Chicago Giants. Foster was a fan of the sacrifice bunt, and for some time he had drilled his team on the skills and benefits of the play. Foster knew, however, that a game-winning example would go a long way toward convincing his young players who were not fond of the idea of giving themselves up to advance a runner.

The game was tied 0 – 0 in the 7th with a runner on first and Jelly Gardner at-bat when Foster thought the time was right. Knowing that Jelly could certainly handle the bat and had good speed, Foster decided that a sacrifice bunt by Gardner would move the runner to second where he could score on a single. One run might be enough in the tightly-contested game.

As Jelly strolled to the plate, Foster moved to the far end of the dugout, took a long draw from his pipe, and blew two perfect smoke rings skyward. The old manager leaned on the dugout rail and waited for Jelly to provide his important lesson. Jelly ripped the first pitch on a line drive over the first baseman and deep into the right-field corner. By the time the right fielder retrieved the ball and got it back to the infield, the run had scored and Jelly stood on third with a wide grin of satisfaction. The smile soon disappeared when a pinch-runner trotted out to take his place. Jelly knew two smoke rings were the bunt sign, but he had other ideas. In the dugout, Foster had no sympathy for his cocky little outfielder and gave him a stern lecture in front of his teammates.

Exuberant at best, and possibly headstrong, Jelly was also known for a quick temper. Negro League teammates tell about one particular incident when he was ejected from a game for vehemently protesting what he thought was a bad call resulting in strike three. He realized too late the ump had called the pitch a ball. Jelly was also a fierce competitor who was quick to fight with opponents or even teammates, if necessary. He once kicked a fellow Giant in the mouth when the teammate tried to break up a fight Jelly was particularly interested in prolonging.

This same competitive fire that made Jelly tough to control and volatile also provided the spirit that made him one of the league’s all-time greats. He played in the Negro Leagues for parts of 16 seasons and played several winters in the Cuban league. Jelly had a lifetime batting average of .282 and when old-timers of the Negro Leagues name their all-time teams, Jelly Gardner is usually chosen the right fielder. Gardner remained in Chicago for the remainder of his life where he worked for the railroad. Floyd “Jelly” Gardner died in Chicago in 1977 at the age of 82.

Buck O’Neil and others worked tirelessly for overdue recognition of African-American baseball players who could have been major league stars but never got the chance. In 2005, due to the work of O’Neil and others, 94 former Negro Leaguers were nominated by a special committee for the Baseball Hall of Fame. One of those players was Floyd Gardner of Russellville, Arkansas.

As of 2023, Floyd Gardner has yet to be selected, but like so many great African-American baseball players who were denied the opportunity to compete in the major leagues, perhaps his time for induction is yet to come.

Housekeeping…

If you have missed some posts click here: Link to access past posts.

More of my stories in Only in Arkansas

If you want signed Hard Times and Hardball or Backroads and Ballplayers: Ordering instructions Link

Important…During the winter, Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly will only be available through free subscriptions or on the Backroads and Ballplayers Facebook page.

Christmas gift for dad