Backroads and Ballplayers #3

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Remembering Aaron Ward and More Possum Thoughts 4-23-2023

Who is Aaron Ward?

One of my goals in this space is to revive Arkansas baseball stories that have been lost over time. I realize 100 years is a long time, but I am troubled that Arkansas baseball fans do not recognize the name, Aaron Ward. After all, he was a big-league star, a headliner in America’s most-read newspapers, and Babe Ruth’s teammate. This week in my monthly essay in the online magazine Only in Arkansas, I wrote a biography of Aaron Ward. I will post a link at the end of this piece in case I have made you more curious about our state’s first World Series star.

I am going to assume that the name did not ring a bell, so here is a hint:

In the 2012 movie Jack Reacher, starring a fellow named Tom Cruise, the name Aaron Ward plays an important role in the story. Okay, Reacher and Cruise you have heard of, but probably not Ward. When Cruise’s character (Reacher) introduces himself as “Aaron Ward” to shooting range manager Martin Cash (Robert Duvall), Cash catches the assumed name immediately. Cash later dubiously confronts Reacher, “You never played second base for the Yankees.” Cash recognized the name of the star of the first Yankees team to win a World Series, but most moviegoers did not.

This week 100 years ago the Yankees played their first game in a new ballpark. The Yanks had shared the Polo Grounds with the New York Giants, but when the Yankees started drawing more fans than their landlords, the Giants told them to go play elsewhere. The “elsewhere” they built was a baseball palace in the Bronx called Yankee Stadium.

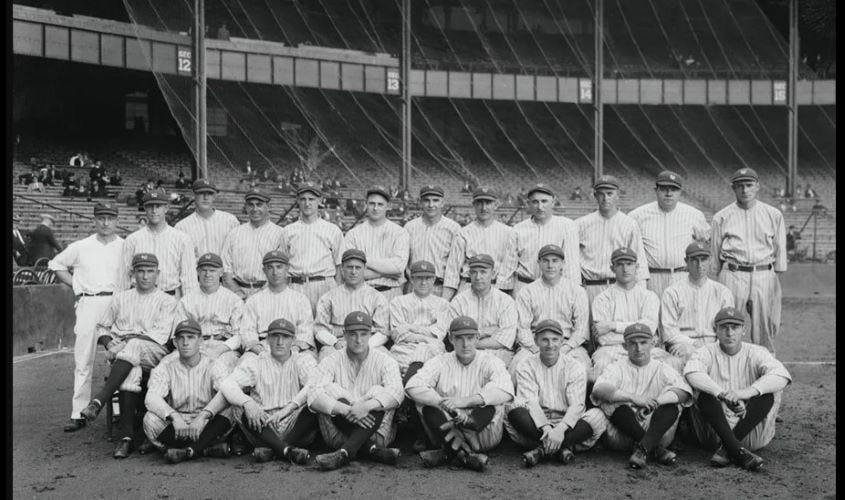

In April 1923, the Yankees had reason to be hopeful that this was their year. After all, on the day after Christmas in 1919, they had snookered Boston out of a pitcher/outfielder named George Ruth, who by his fourth year in the Bronx, had revolutionized the game with his home runs. They had several other good players, including 26-year-old second baseman, Aaron Ward, from Booneville, Arkansas. The Yanks had won two consecutive American League pennants but lost to the hated Giants in both World Series.

Looking back on that 1920 season, Babe Ruth had captured the imagination of the entire baseball world in his first season in New York. The “Great Bambino” hit 54 home runs, more than the combined roster of any team in major league baseball. Think about that!

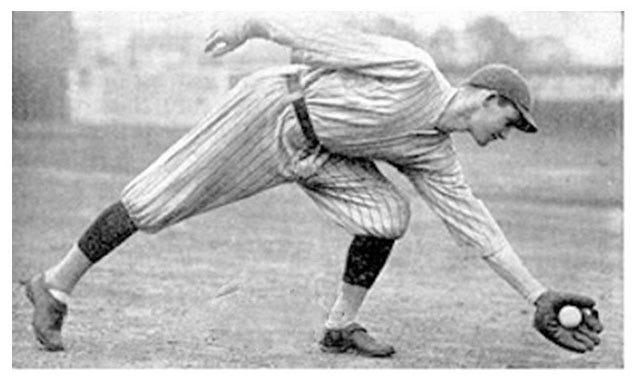

When Baker returned in 1921, Ward moved to second base, his natural position, and remained there for the remainder of his career in New York. Ward raised his batting average to .306 in 1921 and finished third in fielding percentage among second basemen. He no longer had to check the card posted in the dugout to see if he was in the starting lineup. He led the team in games played.

In 1922, Ward finished second in fielding percentage for AL second basemen, and he lead the league in assists. His batting average fell to .267, but once again he led the Yankees in games played. In three years, Ward had gone from a replacement used out of desperation to one of the outstanding middle infielders in the major leagues.

The fielding was expected. Since his college days at Ouachita College (Ouachita Baptist University), Ward had always been known as a better fielder than a hitter. In fact, in his first pro trial, seven games and 18 at-bats for the 1915 Little Rock Travelers, he did not have a single hit. When he was promoted to the Yanks, the Arkansas Gazette recalled his days playing in Little Rock, “He put up a classy game at short, but he couldn’t hit at all.”

On April 18, 1923, the Yankees opened their home season at Yankee Stadium before an announced crowd of 74,000 and reportedly another 25,000 left outside. In the home half of the third inning, the fans got what they came for. A 26-year-old second baseman from Booneville, Arkansas, hit a sharp single between short and third for the first hit in Yankee Stadium. Later in the inning, right on script, Ruth hit the first home run in the new park. Ward got a box of cigars for his historic hit, and the Yankees started the season with a 4–1 victory in what would become the year the “Bronx Bombers” began the ascension to legendary status.

That Opening Day launched the season the Yankees had been building toward since they acquired Babe Ruth and started assembling a competitive team around him. The Yanks coasted to the American League pennant by 16 games and Aaron Ward was now a complete player. Hitting in the middle of the Yankees lineup, Ward hit a solid .284 and drove in 81 runs. He was second on the team to Ruth in homers and triples and led the league’s second basemen in fielding percentage and assists. Yankees’ shortstop Everett Scott declared, “Next to Babe Ruth, Ward is the most valuable man on our team.”

New York's American League team capped the year by defeating their arch-rivals, the Giants, four games to two in the 1923 World Series. It was the third consecutive year the bitter rivals had met in the fall classic and the first championship of the 20th century for the Yanks. Ward led all World Series hitters with 10 hits and a .417 batting average. He handled 38 chances in the field without an error, including the last out—a weak ground ball to second base.

Back in Logan County, Arkansas, they were listening on the radio. “When our Wardy got a hit…folks over in the next county knew it by the cheers.” The Yankees and Aaron Ward were on top of the baseball world that World Series of 100 years ago, but Ward had ascended to a career peak rather than a plateau.

Knee problems that had followed him from his football days at Ouachita, began to erode his speed and quickness. He played in only 120 games in 1924, the lowest total since 1919. His batting average dropped more than 30 points, and, more critically, his range at second base was greatly reduced. The Yanks fell to second place behind the Washington Senators.

The 1925 season was worse. Ward, still plagued by nagging injuries, played 125 games and hit .246. Perhaps indicative of the Yankees’ long-range inclinations, the club cut Ward’s salary from $10,000 to $8,000.

As expected, the Yankees replaced Ward with future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri in 1926 and traded him to Chicago in January of 1927. After a mediocre season with the White Sox and six games with the Cleveland Indians, Ward played his last big game in June 1928, just five years removed from the 1923 season when he was the outstanding second baseman in the American League.

In the first six years of the '20s, Aaron Ward witnessed the ascension of Babe Ruth to the “Great Bambino” and the second-division Yankees’ transformation into the “Bronx Bombers.” No one played more games for the Yanks during those formative years than the second baseman from Arkansas.

Despite his stardom in the early 1920s, Aaron Ward’s place in baseball history is largely overlooked. His accomplishments were soon eclipsed by the Yankees who followed him and the arrival of charismatic stars like Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri. Perhaps more lamentable and difficult to explain is that Aaron Ward seems to have been forgotten in Arkansas. Despite becoming Arkansas’ first major league star, Ward has yet to be inducted into the Ouachita Baptist University Hall of Fame or the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame.

More Possum News

I had just wrapped up last week’s column when the Oakland A’s made sports page headlines by evicting a possum from their visitor’s broadcast booth. I had a theory immediately. Things are not going well for the A’s…like 1962-Mets bad. The inept A’s are on schedule to lose 100 games by Labor Day!

In my imagination, I saw this emergency meeting of the A’s staff to develop a strategy that might draw a crowd as large as the local tractor pull. An intern from somewhere down this way suggested a mascot upgrade. “The Arkansas Travelers have a possum that folks seem to like.” “Okay, get us one.”

Now, folks are not very possum-savvy out on the bay, so the young intern brought in a live one and created a home in the visitor’s broadcast booth. It didn’t work for attendance or the possum. The visiting broadcasters complained about the smell and the little fellow was disrespectfully dismissed.

In the team’s official version, the little fellow strolled across forty acres of parking lot, climbed up three stories (elevator?), found some kind of food supply, and made himself some living quarters in the booth. I really like my story better. In any case, the A’s were embarrassed, but they are apparently headed for a new home in Las Vegas anyway.

Henry Pierson Moore

In the list of the greatest minor league teams in the 20th century created for the centennial celebration of the National Professional Baseball Leagues, five of the top 50 were Fort Worth Panthers teams from 1920-1925. The catcher on those teams was a colorful character called “Possum” Moore. A fiery no-nonsense competitor, Moore was the catcher and captain of those great Fort Worth teams. His obituary in the Sporting News in April 1958 rates him among the best catchers in Panthers’ history. “Henry P. Possum Moore, 66, was rated one of the greatest catchers ever to play with Fort Worth (Texas).” Of course, Henry P. Moore was born, on March 18, 1892, in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Link to Aaron Ward’s story in Only In Arkansas due out Monday, April 24.

One hundred total subscribers and 350 reads last week, thanks!