Backroads and Ballplayers #28

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Book Report, Post-Season Thoughts, and Boss Schmidt, Arkansas First World Series “Star.”

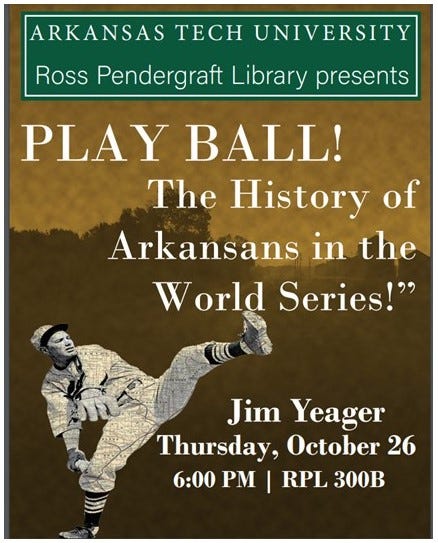

The next two weeks are going to be hectic on the “book tour.” Before I go into the library meet and greet events, I want to encourage you to attend the “World Series Eve” event at Arkansas Tech on October 26. If you have heard me tell old-time baseball stories before, I assure you this is a completely new presentation. As you know, Arkansas has produced some of the most colorful players in major league history. Many of them had significant roles in the World Series.

We have found more than a dozen tales from baseball’s early days through the 1970s when an Arkansas-born player made World Series headlines. Sometimes historic, sometimes poignant, and sometimes humorous, these players and their World Series moments are a valuable part of our baseball heritage. I look forward to sharing them. I appreciate Arkansas Tech’s sponsorship of this evening and I am confident that you will enjoy our “The History of Arkansans in the World Series” presentation, on October 26, 6:00 - 7:00 p.m. Library 3rd floor

Playoff Thoughts

Here is what we know about the baseball playoffs. We don’t know anything! I remember the 2008 Super Bowl very well. The New York Giants, a wild card team with a 10—6 regular season record, beat Tom Brady’s undefeated Patriots 17—14. Well, I thought, anything could happen in one game. If these two teams played a series, the Pats would surely win. Baseball would certainly take care of that anomaly with a seven-game series. Maybe not.

The 2023 Atlanta Braves won 104 regular season games. They are out. The Dodgers won 100. They are out. In the American League, Baltimore won 101 and the innovative Rays won 99. They too are out. We have three teams left that won 90 regular season games and one that won 84. This leaves a lot of “experts” burdened with the task of explaining what the regular season means.

I am conflicted about the current playoff process. I am sure fans of those excellent eliminated teams I mentioned earlier are also dubious of the system now in place. Most of us in the “over 60 and out of touch crowd” fondly recall the simple old postseason plan with league champions meeting in the World Series. We also liked CB radios before cell phones, so we might be nostalgically afflicted.

After watching the playoffs so far, I can say one thing with certainty. The fans love it. Marginal baseball fans are at the game and watching their home team play in a win-or-go-home format, and they are beginning to understand how baseball is different. Most sports are dominated by “reaction moments” like a three at the buzzer in basketball or a walk-off field goal.

Baseball has that kind of thing too, but it also has “anticipation moments.” Maybe it is an eight-pitch at-bat with the winning run at third. It seems like an eternity of pitch-by-pitch tension, followed by elation or anguish. Or it could be as brief and intense as a center fielder chasing a long drive toward the wall with the bases loaded. The result will be the double that wins the game or the final out. For those three seconds, victory and defeat hang in the balance.

It does seem like the game is making a comeback and many younger fans are “getting it” for the first time. I hope more fans watching more playoff games bring a new appreciation of the game to younger fans.

The picture of Nick Castellanos’ son enjoying a lifetime moment says it all. Watch a playoff game and see why we love baseball.

(Why We Love Baseball is the new bestseller by my favorite author, Joe Posnanski.)

I have no idea who will emerge as World Series Champion, but I predict it will be chilly in Philly in November.

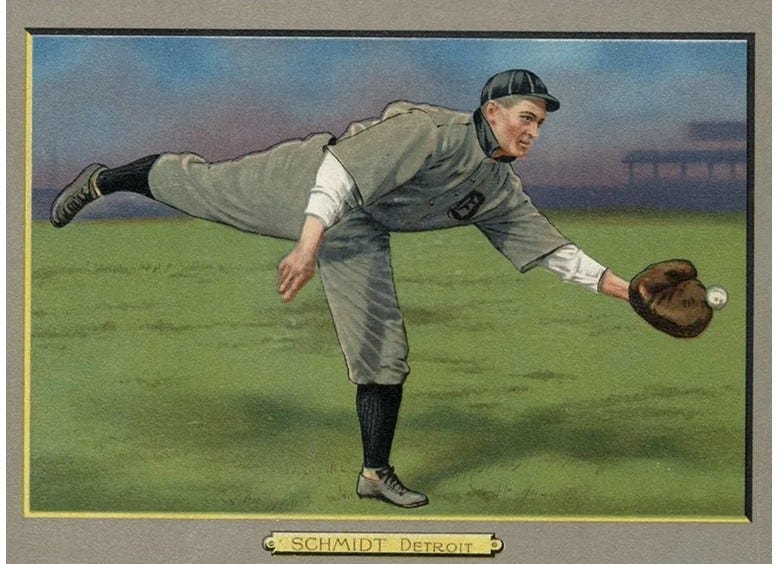

Charles “Boss” Schmidt

The first Arkansas-born player to appear in a World Series was the almost legendary Charles Schmidt. Born in London, and raised in Coal Hill, Schmidt was one of the most popular players of his time, and not always because of his work on the baseball field.

Schmidt was born in London, Arkansas, on Sept. 12, 1880. He grew up in the heart of the Arkansas coal belt at a time when Coal Hill was a mining boomtown. One of the strongest and toughest of the young coal workers, Schmidt earned the nickname “Boss” from fellow miners. His physical strength and toughness would serve him well in pro baseball, where his reputation as the consummate gritty backstop followed him his entire career.

Schmidt appeared in his first professional game for the Little Rock Travelers in August of 1901, without coming to bat. That inauspicious beginning was followed by four successful minor league seasons and a promotion to the American League Detroit Tigers in 1906.

Defensively, Schmidt was more courageous than skilled. Armed with the tools of the day, a rudimentary mask, thin chest protector, and a mitt that resembled a throw pillow more than a glove, Schmidt often defended the position rather than manning it. With no shin guards and numerous broken fingers, he was often injured, but seldom unavailable to play.

From 1901 until 1926, baseball was Boss Schmidt’s profession. The Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia credits Schmidt with 2076 games played. Baseball-Reference.com has his career total at 1957. Baseball-Reference has no record of games played by Schmidt after 1924, but the Kalamazoo Michigan Gazette of May 28, 1926, proudly boasted that the Kalamazoo Celery Pickers’ player-manager, “Uncle Charley Schmidt crashed out a mighty wallop to deep center field that sent the Big Boss around to the third corner.” He was obviously still playing at age 45 and perhaps longer.

Boss spent six seasons with the Detroit Tigers from 1906 through 1911. Never known as a good hitter, his major league batting average was a lackluster .243.

Schmidt led the league in errors from 1907—1909, but in each of those seasons, he was in the top five for games played by a catcher. While Schmidt’s statistical record does not reflect a noteworthy career, he is one of the most renowned major leaguers of his time.

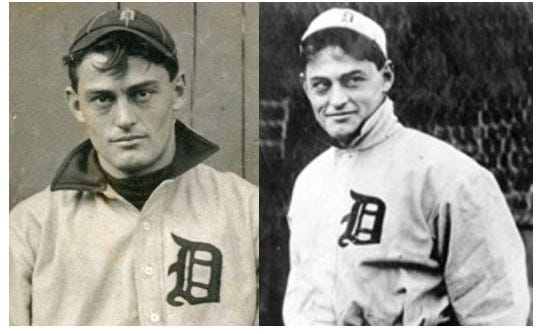

Schmidt’s early claim to Tiger fame was his willingness to physically put the abrasive Ty Cobb in his place, a job his teammates felt needed to be done often. The most famous of these confrontations resulted when Schmidt intervened after Cobb attacked an African-American groundskeeper and his wife. Although Schmidt reportedly gave Cobb a “good plummeting,” he had to administer the same lesson just two weeks later.

In addition to his very public and well-documented fisticuffs with Cobb, tales of Schmidt’s toughness and strength became legendary. In a time when baseball fans depended on sportswriters to help them get to know the players, reports of Boss Schmidt’s exploits, both accurate and fabricated, made good stories.

“I like to do just four things. Play ball, fight, hunt, and eat. Boxing is all right for a little amusement when it’s too cold to play ball…” Boss Schmidt

Before football iron men like Dick Butkus and J. J. Watt were recognized as the tough guys in pro sports, baseball supplied the examples of resolute strength. When shin guards became a standard part of a catcher’s equipment, Schmidt continued to deflect low pitches with his shins.

Could Schmidt actually drive nails with his fists? Apparently, this was one of his favorite tricks, and he especially enjoyed proving this boast when ladies were present. Did Boss Schmidt allow individuals willing to pay $10 to throw a baseball at his chest from a few feet away? This one is probably true. It is an often-told tale.

Regardless of their accuracy, reports of Schmidt’s feats of strength and toughness are not unlike Yogi Berra quotes. Some are true, some are questionable, but the tales are as essential to his legacy as his exploits as a baseball player

In three of his seasons as the Tigers catcher Boss played in the World Series (1907, 1908, 1909). His batting average for those three losing Series was .159. Hugh Jennings, the Tigers’ manager, often faced the wrath of fans and sportswriters for keeping a weak-hitting and defensively inept Schmidt in the lineup. With injuries to his throwing arm limiting his effectiveness, Boss played in only 28 games for Detroit in 1911, his last big league season. He played, managed, and coached in the minor leagues for 15 more years.

The last years of Schmidt’s life were spent struggling to make a life after baseball. He picked up odd jobs around baseball, but eventually returned to Arkansas without his wife and children and lived alone near Coal Hill. On Sunday, Nov. 13, 1932, Schmidt went to a local physician’s home in intense pain suffering from an intestinal obstruction. He died a day later and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Boss would make the local news one last time on Sunday, March 22, 1970. On that date at St. Mary’s Cemetery just north of Altus, Arkansas, a few mourners braved the uncomfortable chilly wind, to pay their respects to Arkansas’s first major league baseball star.

On the afternoon of Sunday, March 22, 1970, family, friends, and local dignitaries gathered to commemorate the placing of a gravestone provided by the Detroit Tigers on Boss Schmidt’s unmarked grave. Arkansas native and Baseball Hall of Famer George Kell represented the Tigers at the ceremony. In addition to the name “Charles Schmidt” and his birth and death dates, the marker reads, “A Detroit Tiger 1906 – 1911.”

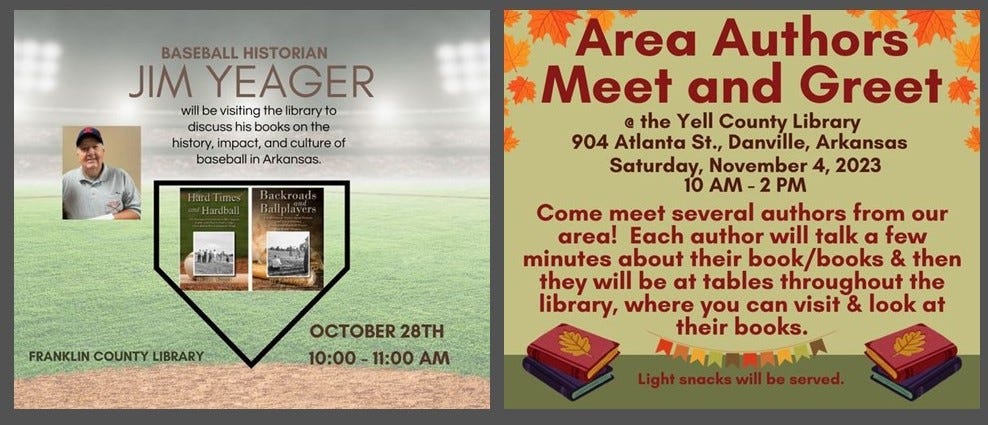

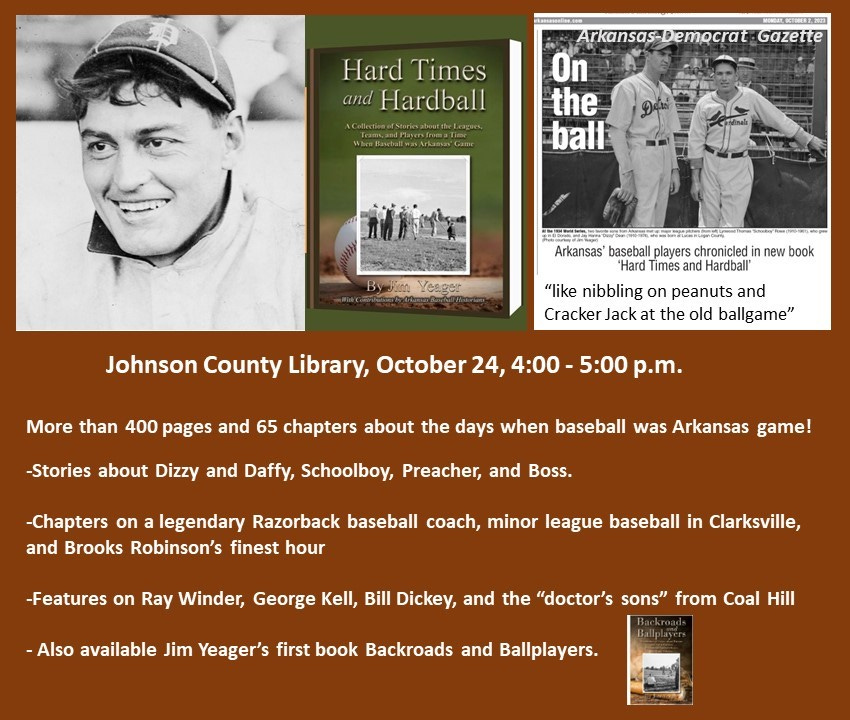

Library Events

If you have missed some posts click here: Link to past posts.

More of my stories in Only in Arkansas

If you want signed Hard Times and Hardball or Backroads and Ballplayers: Ordering instructions Link