Backroads and Ballplayers #24

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Rule Changes, Heston Kjerstad Arrives, and a Love Story

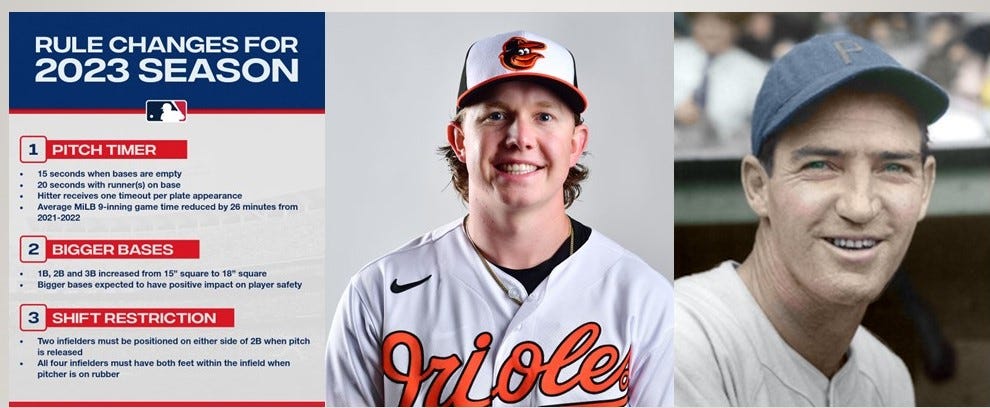

Pitch Timers, Pizza Box Bases, and Over-Produced TV Games

I suspect that most of us were a little skeptical about the rule changes imposed on a core fan base that abhors changes to the “traditions” of our game. I am a born-again Cardinals fan, having been one of those 50s kids who loved the Mick until we realized it was Mantle, not the pinstripes we liked, but last season, it was agony watching Giovanny Gallegos in the late innings between Pujols at-bats. In Arkansas terms, his “piddling around” did give the Cardinals home broadcast guys time to discuss the fun the return of the prodigal son had provided, but it took a lot of games well past my bedtime.

In this post, I am sharing my story that appeared in Only in Arkansas last week about Schoolboy Rowe talking to the baseball. I didn’t see Giovanny talk to the ball, but he hugged it, rubbed it, and strolled around with it for uncomfortable length between pitches. Maybe that was his plan to drive hitters to distraction. Nonetheless, his kind, and the glove adjusters, armor checkers, and step-out-between-pitch guys had made the game tedious, even for those of us willing to accept almost anything. Oppenheimer was three hours and nine seconds long. Last season, the average baseball game was longer. I like two hours and 40 minutes much better. So, even though I do not like the “runner on second in extra innings” rule, I am giving the collection of new rules a general approval far beyond my traditionalist’s expectations.

Now, if we can stop interviews with managers between innings, and omit the new feature of sending a mic out to left field with Kyle Schwarber to chat while the game is going on. Could we also outlaw any interview question that is longer than 100 words or contains the phrase, “How does it feel?”

I saw a game a few weeks ago when the pitcher wore a wire to discuss his strategy with us. To me, but perhaps not most fans, this stuff disrespects the game. I do admit, however, that I sometimes wonder what Dak Prescott was thinking.

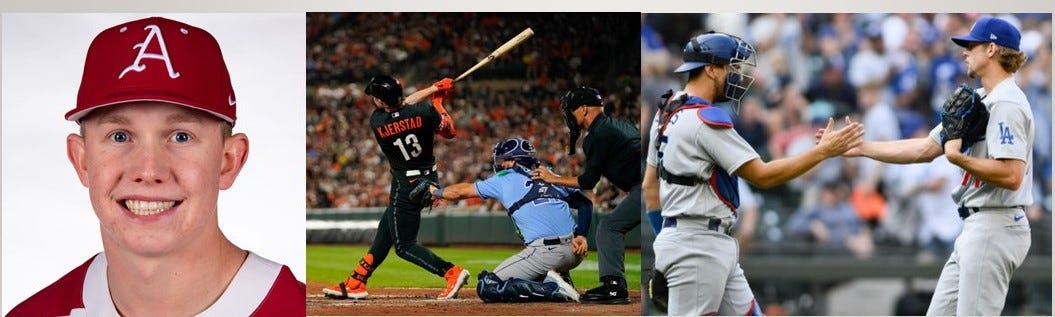

Welcome to the “Show” Heston Kjerstad

One unique thing about a baseball season is the sports drama/human interest story of call-ups and demotions. “Transactions” has its own heading on the online ESPN MLB Website.

On Thursday, September 14, the playoff-bound Baltimore Orioles made some housekeeping transactions. They promoted Greg Bader to executive vice president and chief operating officer. The team named Kerry Watson executive vice president of public affairs and Lisa Tolson senior vice president and chief “people officer.” Oh, and the Orioles promoted Heston Kjerstad from Norfolk in the AAA International League.

It has been a long trip to what surely was Kjerstad’s inevitable baseball destination. The Orioles took him second in the 2020 MLB Draft, paid him less than that lofty spot usually demands, and used some of the loose change to add some more quality young players to an impressive collection of minor league talent. Kjerstad got a good payday, joined an up-and-coming organization, and looked like a sure thing, but it was 2020!

The 2020 minor league season was canceled altogether. Covid-related myocarditis cost Kjerstad all of the 2021 season and he missed the spring of 2022 with a hamstring injury. Entering the 2023 season Kjerstad had accumulated only 286 minor league plate appearances.

In 2023, he quickly outgrew AA at Bowie in the Eastern League, and despite a September slump, he continued to put up impressive numbers in AAA. His totals for the year in both levels were a .303 batting mark, 21 home runs, and a .904 OPS.

On September 14, Kjerstad struck out in a pinch-hitting appearance in his first big league game. He got his first start on September 15 against the Rays before 43,000+ at Camden Yards. After striking out in his first at-bat in the bottom of the third inning, Kjerstad led off the sixth facing veteran Zach Eflin, who happened to be the American League leader in pitching wins and the ace of the Rays’ staff. Incidentally, the Birds were down 7—0, and Eflin was working on a no-hitter. It was not a promising spot for a rookie with two strikeouts in two big league at-bats.

On the third pitch, Kjerstad hit a low breaking ball 418 feet, deep into the right field stands. It looked very familiar…a pitch on the inner half of the plate launched into the night by a young guy with that beautiful long sweeping swing. Welcome to the “show” Heston Kjerstad.

By the way, Gavin Stone (Lake City, UCA) made another trip to join the Dodgers last week. It was his sixth flight to join the big league club. By now he knows how to do it, but this time with the big club planning some R and R for their essential pitching staff heading into the playoffs, Stone stayed for a road trip. On Sunday he picked up a save in three and a third innings in Seattle.

A Baseball Love Story, Only In Arkansas

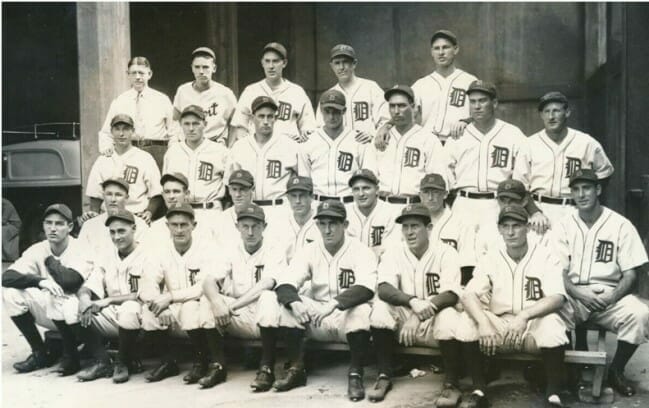

I write a monthly piece for the online magazine Only in Arkansas. Sponsored by First Security Bank, OIA is an outstanding collection of interesting and informative stories about our great state. The posts include travel suggestions, special events, Arkansas dining, and features on notable Arkansans. Only in Arkansas also has one baseball history writer. I am honored to be associated with this excellent publication. My story which appeared for the first time last week is one of my all-time favorites. It features the 1934 season in the career of Union County’s Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe.

A Baseball Love Story, Schoolboy Rowe, and Edna Skinner

It’s almost 9 o’clock honey and I am just on the verge of a-goin to bed. Tomorrow is the big day, so they tell me. They are depending on me to win one for the Tigers and if I do, I will tie the American League record for consecutive victories…Take care of yourself and while I’m whizzing them down the middle tomorrow, I’ll be thinking about my honey down in El Dorado. And when I think of you, honey they can’t beat me.

About 100 years ago, a young fellow with the scholarly-sounding name Lynwood Thomas Rowe arrived in Arkansas from Waco, Texas. Often described as tall and lanky for his grade in school, young Lynwood was likely two years older than his new classmates. Although he was not exactly a scholar, Rowe had extraordinary talent.

He was destined to emerge from small-town obscurity to become a sports writer’s dream. Lynwood Rowe had it all. He was an outstanding athlete and excelled in several sports. He was also tall and handsome with a southern charm that made good press. Rowe was quirky, superstitious, and quotable…And he had a love story.

Upon his arrival at Hugh Goodwin Elementary in El Dorado, Lynwood was immediately smitten by a classmate named Edna Mary Skinner. Unfortunately, Edna had a boyfriend named Fred, so Rowe volunteered to hang out with Edna and Fred to act as a bodyguard. The plan worked well for Edna and Lynwood, but not so much for Fred. Young Edna took a fancy to the bodyguard. From those grade school days until he became a major league sensation, Edna Mary Skinner was a major part of the saga of Lynwood Rowe.

Lynwood Rowe, called “Speck” by his family and friends because of an abundance of freckles, was an immediate star in elementary school sports. By the time he was 15 years old, the El Dorado Daily News semi-pro team had “hired” Rowe as their pitcher in the adult Twilight League. The team sponsor gave their teenage hurler free newspapers to sell after the game. The proceeds would serve as Lynwood’s “salary.”

The sports editor of the Daily News gave Lynwood a much-needed nickname. First, the paper called him “Newsboy Rowe” and later upgraded his moniker to “Schoolboy Rowe.” Now sporting a catchy nickname, the kid pitcher not only made local headlines but regional papers also began to cover the exploits of El Dorado’s “Schoolboy” pitching prodigy.

Although Rowe signed with the Detroit Tigers as a teenager, he remained at El Dorado High School until his graduation in 1931. Rowe was assigned to Detroit’s farm team in Beaumont, Texas, in 1932. He was joined in Beaumont by another young Tigers prospect named Hank Greenberg. Future Hall-of-Famer Greenberg hit 39 homers to lead the league, and Rowe’s 2.30 ERA was also the best mark in the Texas League. The Beaumont Explorers won the pennant and the league playoffs. By the next summer, both Rowe and Greenberg were promoted to the majors.

Rowe went 7-4 with the Tigers in 1933. He got off to a good start as the club’s fifth starter, posting a 3.58 ERA in 123 innings, but a shoulder injury ended his season in late July. Greenberg hit .325 in his rookie year, but the Tigers finished 75-79 in fifth place in the American League. There was little indication in the Detroit club’s season to predict the magic summer of 1934.

The beginning of the 1934 season did not reveal that Schoolboy Rowe would have a career-defining year and one of the most remarkable seasons in Major League history. He entered June with only two pitching victories and an ERA approaching six runs a game. He continued to complain about the sore arm that he carried over from the previous season. The press and some of the Tigers’ leadership began to look at the arm problems as an excuse for poor performance. All those doubts and innuendos vanished in mid-summer when Rowe began an epic winning streak.

On June 15, the Tigers and Yankees were virtually tied for the league lead, and Schoolboy Rowe’s record stood at four wins and four losses. Rowe pitched a complete game in an 11-4 Tigers win over Boston that day, but nothing in his performance indicated the historic win streak that began with his fifth victory. Although he was the winning pitcher, Rowe gave up nine hits and four runs, raising his ERA to 4.14. He posted one more victory in June and entered July with a 6-4 record and a lackluster 4.17 ERA.

July was a much different story for both Rowe and the Tigers. Schoolboy won 8 pitching victories in the month, and the Tigers moved into first place. Rowe had posted 10 consecutive victories by Aug. 1, lowered his ERA to 3.62, and caught the imagination of a city hungry for a pennant. His Future Hall of Fame teammate, Hank Greenberg, raised his batting average by 33 points in July and drove in 28 runs. For the first time in 35 years, Detroit fans could imagine the American League Pennant flying over Navin Field.

As the season moved into August, the Detroit Free Press knew there was another story to tell associated with Schoolboy Rowe’s assault on the league record of 16 consecutive pitching victories. Suddenly everyone wanted to know what Edna Mary Skinner was thinking down in Arkansas. As Rowe approached the consecutive victory record it was hard to determine if fans were more enthralled by the on-the-field excitement or the personal back-story of Schoolboy and Edna Mary.

Schoolboy’s uncomplicated county-boy personality won the hearts of Detroit fans. He was handsome, bucolically charming, and profoundly superstitious. He had a disarmingly honest way about him that softened even the toughest critics. His unsophisticated rural ways were exactly the expected persona that the Deans and Lon Warneke had established for Arkansas pitchers, but to his expected provincial personality, Rowe added an amusing quirkiness. He armed himself with a pocket full of lucky charms and amulets to fend off evil spirits and, when necessary, called on his girl back home for help on the mound. Although Edna was hundreds of miles away in Arkansas, Rowe would often address her through the ball as he stood on the mound. “Edna, Honey, let’s go,” was his preferred pep talk.

Perhaps Rowe’s most enduring quality was his obvious affection for Edna Mary Skinner. His public infatuation with his high school sweetheart was part of his charm, and Rowe made no effort to hide it. One of the most retold examples of Schoolboy’s obsession with Miss Edna came during an interview with radio personality Eddie Cantor in September 1934. In the middle of the program, without regard for Cantor’s question, Rowe could no longer contain his most important thought. Schoolboy leaned into the mike and posed the question, “How am I doin’ now, Edna?” The delightfully charming question would endear him to his Detroit fans and provide a taunting yell for the opponents. For the remainder of his career, if things went wrong for Rowe on the mound, a loud voice would boom the question, “How am I doin’ now, Edna?”

When Rowe won his 16th consecutive victory on August 25, everyone in Detroit wanted to know how Edna Mary Skinner of El Dorado, Arkansas, felt about the big win. Under the headline, “It’s a Big Day for Edna and All El Dorado,” the sub-heading read, “Schoolboy’s Fiancée Just Knew That He Couldn’t Fail.”

The article went on to include Edna’s first comments after learning about the win, “I am tickled to death,” said the excited 22-year-old. The story continued with the news that the town of 17,000 was getting a train together for a trip to the World Series. The leaders of the contingent would be Edna Mary Skinner and her father.

The Tigers won the American League pennant going away, which set up a historic Arkansas World Series that would match the American League Champions led by Schoolboy Rowe and the Gas House Gang St. Louis Cardinals that featured Dizzy and Paul Dean.

Note: During football season and maybe from now on, look for my weekly post on Monday.

If you have missed some posts click here: Link to past posts.

More of my stories in Only in Arkansas

If you want signed Books: Ordering instructions Link

Tonight, Monday, September 18, 7:00 PM join me at Farmers Bank in Greenwood for a presentation and book signing.