Backroads and Ballplayers #19

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Rube and the Babe, and Back to School

Rube and The Babe, This Day in Baseball

Occasionally, if it appears on my screen through some sort of audience targeting, I see a promoted blog called “This Day in Baseball.” I wish I had thought of it. The idea of obscure baseball stories buried in the more significant history of the game is right down my alley. I love to uncover a lost story from the not-so-obvious history of Arkansas baseball. When asked, “What does Jim write about,” my wife’s usual answer is, “He writes about things no one really cares about.” The fact that hundreds of you read this each week, doesn’t seem to convince her that you actually exist.

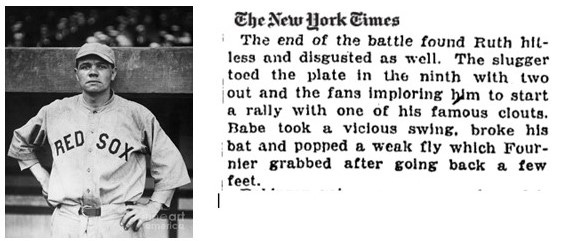

I am writing this in the early hours of Saturday, August 12, and I am reading This Day in Baseball intentionally rather than accidentally. My friend Fred Roberson tipped me off about today’s post a few days ago. It concerns John Henry Roberson, AKA Rube Robinson, AKA Hank Robinson, and his last game in the big leagues. It is not factually correct, but I doubt it has ever been edited since it was posted the first time.

From: Thisdayinbaseball.com

This day in baseball August 12, 1918:

At Fenway Park‚ the Yankees win their 10th of 15 games with the league leaders by beating Boston‚ 2—1. Getting his opportunity because of the war‚ lefty Hank Robinson* is making his first major league start since 1915.** He allows just 3 hits in besting Babe Ruth‚ who gives up 4 safeties. Jack Fournier scores the winning run on a squeeze bunt‚ while Ruth‚ hitless on the afternoon‚ pops out for the last out of the game.***

*Hank? Where did “Hank” ever come from? John Henry is Hank Robinson only in Baseballreference.com.

**Actually, his first start since the previous week, but I will admit three years is a better story.

***True! They got this one right.

Below is from Fred Roberson’s email:

My grandfather was pitching for the NY Yankees in 1918 and Ruth was still with the Boston Red Sox. Ruth popped up for the final out going hitless. I have attached a copy of the NY Times article on the game which ran on Aug. 13. My grandfather was a 1962 inductee into the AR Sports Hall of Fame and was a 2011 inductee into the Texas League Hall of Fame on the basis of his 28-7 record in his lone season with the Fort Worth Cats in 1911.

For some reason, some sportswriters nicknamed him Hank and his name was often spelled as Robinson. In his many years after 1918 pitching for the Travelers, everyone knew him as “Rube”. I never heard anyone call him Hank.

I did forward it, but I would be surprised if anything in this post ever changes.

Back to (Baseball) School

This is the time of year you hear the phrase “back to school” so often it seems to be associated with every facet of our daily lives. For 66 years as a student, coach, and teacher it was my way of life. Now retired, I look forward to the first day of school as the chief indicator of the perks of retirement. I don’t have to go!

This month also reminds me of Hot Springs Baseball Weekend. The annual celebration of America’s Pastime takes place this year on August 25 and 26 at the Hot Springs Convention Center. I will write about the event next week in this space.

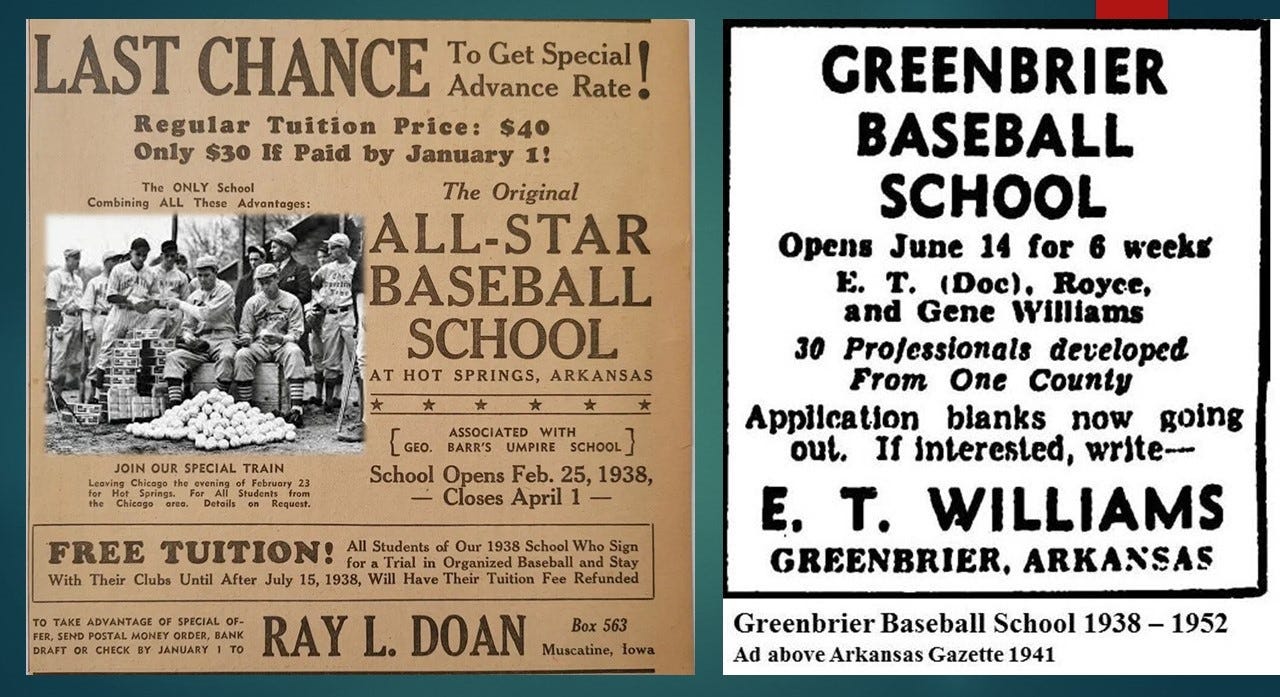

Incidentally, Hot Springs was the site of another kind of first day of school from 1933 until 1938, when promoter Ray Doan operated the Doan Baseball School in the Spa City. What more appropriate location for a baseball academy than the city that was synonymous with baseball spring training up until World War II?

According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, “Young men traveled from all parts of the country to attend this school, hoping to sign a professional baseball contract.” The spring session opened in late February and ran until about April, a pretty unpredictable time of year in the Ouachita Mountains.

Doan moved on to warmer locations in the early 1940s, and Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby tried a similar venture for a time before the unpredictable weather doomed the Hot Springs Baseball School. Hot Springs Baseball historian Mark Blaeuer’s Reaching for the Brass Ring: A Portrait of Doan’s 1937 Baseball School is the definitive essay on the “baseball school days’ in Hot Spring. Link

A country doctor makes Greenbrier the center of early 20th-century baseball in Arkansas.

In the 1930s, the Sunday Edition of the Arkansas Gazette featured a “magazine” section, not unlike the special inserts in the Sunday editions found in today’s large newspapers. The Arkansas Gazette Magazine allowed for more in-depth articles and often included features on the accomplishments of noteworthy Arkansas citizens. The Sunday magazine of June 23, 1935, featured a lengthy article about Earl T. Williams, a country doctor from North Faulkner County. Surprisingly, Dr. Williams’ tribute did not include extraordinary work as a rural doctor, although his work in that field was probably significant. The glowingly laudatory feature by columnist V. V. Quertermous focused on Williams’s leadership in the development of Arkansas baseball players. In retrospect, while his contributions to Arkansas’ baseball prior to 1935 were significant, Williams’s most important work was still ahead.

Dr. Earl T. Williams was born near Hannibal, Missouri, in 1881 and arrived in Greenbrier, Arkansas to set up his first practice in about 1908. His interest in baseball originated in his youth, and although he did not have the skills to play professional baseball or the time to hone those skills, he possessed a deep love for the game.

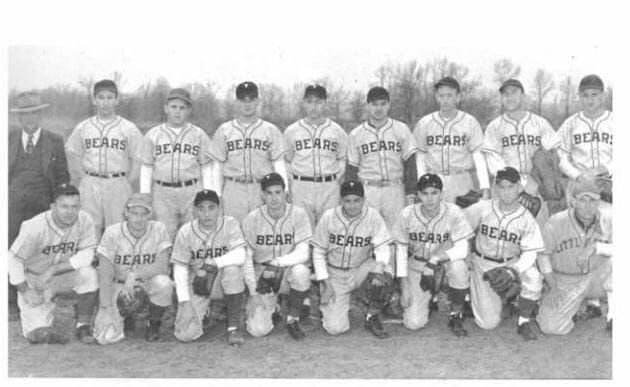

By 1913, Dr. Williams had become the coach of the local town team in Greenbrier, and in 1916 he helped establish a semi-pro league called the Faulkner County League. In the early 1920s, Williams’s interests began to change as his involvement in amateur baseball grew. Traditionally, the manager of a semi-pro team found players, scheduled games, and made a lineup. Perhaps influenced by his advanced education, Williams became interested in player development. He continued to look for talent, but Williams took an extra step uncommon in semi-pro baseball. He coached. Williams studied player skills and drilled his players on proper technique. He became what in today’s sports jargon is called “a student of the game.”

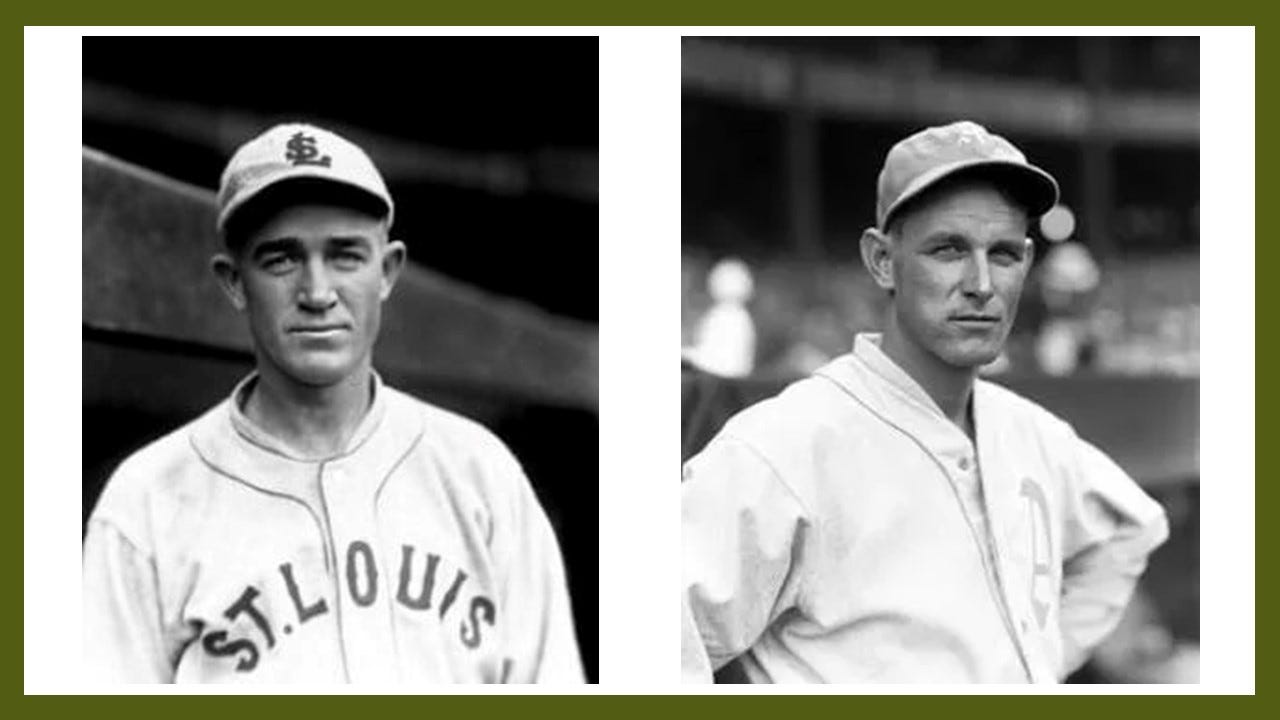

The success of Williams’ semi-pro teams did not go unnoticed. Not only was the Greenbrier semi-pro team successful as a unit, but individual players on the team also began to get noticed. As a result, Williams’ players caught the attention of professional baseball scouts, and young men from tiny hamlets in North Faulkner County, Arkansas began signing minor league contracts. The first of these was Otis Brannan of Greenbrier, who had been an outstanding college baseball player at Arkansas State Normal School (University of Central Arkansas), as well as a star on the Greenbrier semi-pro team. Brannan would become the first player mentored by Dr. Williams to make the major leagues when he became the starting 2nd baseman for the Saint Louis Browns in 1928. He would play professional baseball for 13 seasons.

Although Otis Brannan was the first player who played under Dr. Williams to reach professional baseball and the first to reach the major leagues, he was closely followed by more Greenbrier-trained players in the late 1920s. Among these were Dr. Williams’ two oldest sons.

Royce Williams, the oldest Williams son, graduated from Hendrix College in 1924, after a stellar career in four sports. By 1929, the elder Williams son was 26 years old and had worked his way up through the minor leagues to become the starting second baseman for Class A Memphis in the Southern Association. Royce Williams would have a ten-year pro baseball career but never made the major leagues.

Williams’ middle son, Dibrell, came home from college in the spring of 1929 and became an instant success that summer with the Little Rock Travelers. By the winter of that year, Dib Williams had been signed by the Philadelphia Athletics and was destined to be Greenbrier’s second major leaguer the next spring. Dib Williams would play 475 major league games and another 1200 plus minor league games. He was part of two pennant-winning seasons for the Philadelphia A’s and batted .320 in the A’s 1931 World Series appearance.

A third son, Gene, was eight years younger than Dib and would break into pro baseball in 1936 with Batesville in the North East Arkansas League. The younger Williams son was not as successful in professional baseball and his lifetime record in Baseball Reference.com is inaccurate, but he probably played four years of minor league baseball.

Dozens of North Faulkner County young men who trained under Dr. Williams joined Otis Brannan and the Williams sons in pro baseball in the next decade. By the late 1930s, the country doctor had become the most influential and respected person in Arkansas baseball. In 1938, Dr. Williams decided to take on his most ambitious endeavor.

Doan’s summer school was drawing more than 300 young men with major league dreams to Hot Springs, Arkansas, each February. Big league instructors made the school attractive, but February in Hot Springs was often bitterly cold. Hot Springs also had a rather rowdy reputation, and some families were reluctant to send their inexperienced young sons to a town with unfamiliar temptations. Influenced by the baseball school concept, Dr. Williams came up with what he thought was a better idea, a baseball summer school in a mom-approved, less distracting town.

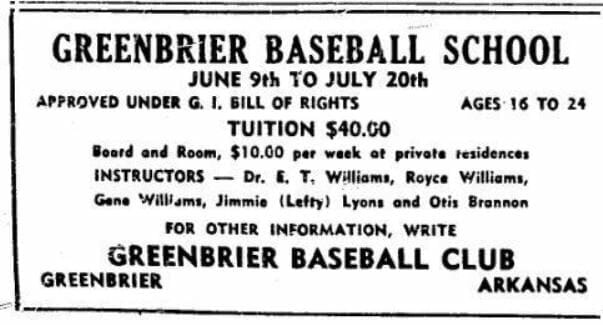

In April of 1938, an ad in the Arkansas Gazette announced the inaugural Greenbrier Baseball School opening on June 14 of the coming summer. Dr. Williams had the name recognition and respect in Arkansas and neighboring states that gave his fledgling summer baseball school instant credibility.

The Greenbrier Baseball School would feature instruction by Williams and his sons, Royce and Gene, in a rural setting devoid of “honkytonks, beer joints, and pool halls.” Tuition would be the standard $50, but for $10 more per week, the young men would be housed by families and fed home-cooked meals.

The first Greenbrier Baseball School enrolled 30 young men in the summer of 1938, and the school was declared an instant success. Some of this success was due to the fortuitous arrival of a tall, lanky first baseman fresh from his high school graduation in Memphis.

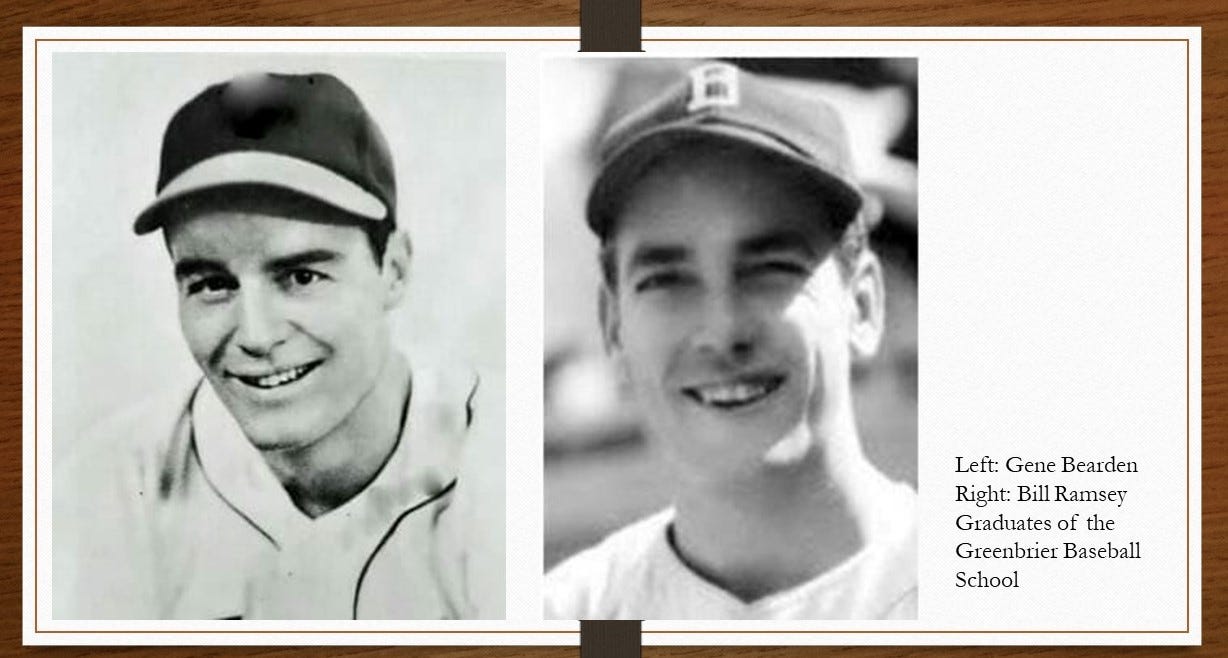

Doc Williams immediately converted the talented lefty to a pitcher, and Gene Bearden became the outstanding player of that first summer baseball school. Bearden attracted scouts to Greenbrier throughout the summer and created opportunities for other participants to catch the attention of pro scouts. Williams reported in July that five young students had signed pro contracts.

In 1939, after his second summer school, Dr. Williams announced several more students had signed with minor league teams. Among those inking minor league contracts was William Thrace “Square Jaw” Ramsey, a fleet-footed outfielder from Osceola, Arkansas.

Ramsey and Gene Bearden would eventually reach the major leagues, and Bearden would become the hero of the 1948 World Series. The Greenbrier Baseball School was off to an impressive start on a 13-year run that produced dozens of professional baseball players.

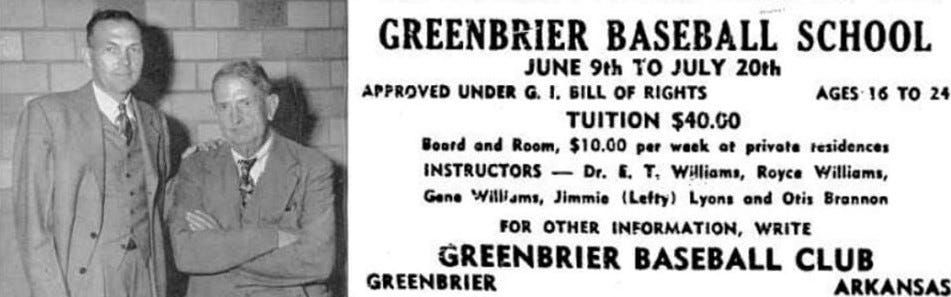

Although Bearden and Ramsey would be the only major leaguers to come from the Williams school, the Greenbrier Baseball School continued to be a popular summer destination for aspiring baseball players throughout the war years, and Dr. Williams became nationally recognized for his leadership in amateur baseball. In 1941, the Amateur Baseball Congress named Williams as the “National Amateur Baseball Leader of the Year.”

In 1947, Arkansas State Teachers College, in nearby Conway, Arkansas, called on Dr. Williams to help the college revive the school’s dormant baseball program. Williams, assisted by his son Dib, coached the team in the spring of 1947, and Dr. Williams taught a class to train future coaches. Ninety students enrolled in the class, and according to the ASTC yearbook from 1947, the “highlight” of the new program occurred when Yankee great Bill Dickey visited the school at Williams’ request, to help build interest in baseball.

In an interview with the Arkansas Gazette in 1949, Dr. Earl Williams fielded the tough question that baseball historians ponder in researching his outstanding career. Columnist Joe McGee asked the 68-year-old country doctor, “What would you do if you had a baby case and there was a ball game at the same time?” Doc Williams replied, “I’d be at the game I guess.”

About two years after the revealing interview, on January 29, 1951, Dr. Earl Williams was in downtown Greenbrier when he experienced the first symptoms of a heart attack. He managed to drive to his home but died a few minutes after arriving there. In a career that unquestionably exemplified the title “Dr. Baseball” given to him in that Sunday Magazine in 1935, Dr. Earl Williams supported the hopes of young men with aspirations of professional baseball for more than 40 years. The Williams family made an obscure little ballpark in rural Faulkner County, Arkansas’ “Field of Dreams.”

Next Week: Hot Spring Baseball Weekend

Have you missed previous posts? Link to Backroads a Ballplayers #1—#18

Where to buy my new book, Hard Times and Hardball. Petit Jean Coffeehouse, Dog Ear Books, Russellville, Arkansas Bookish Emporium, Heber Springs, and mail order at this link.