Backroads and Ballplayers #17

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Join Us on August 12 at Arkansas SABR, “Book Tour”, & Smudge

Follow Me to Robinson-Kell SABR, August 12…

My most asked question: “What made you decide to write books about Arkansas baseball history?” I was a history major in college. I love research, and I love baseball, but attending the Arkansas Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research was the single most motivating factor in my decision to try to save the history of a time when baseball was “Arkansas’ Game.” At the Robinson-Kell Chapter of SABR, I found a group of like-minded baseball fans who enjoyed sharing the stories of their grandparents’ baseball heroes.

I would encourage anyone who loves the game and is interested in the history of baseball in Arkansas to join me at our SABR meetings. The Arkansas Chapter of SABR is named Robinson-Kell in honor of our Hall of Fame third basemen, it is free, and no SABR membership is required to attend the meetings as a guest.

Your Invitation to Robinson-Kell SABR, August 12, Bryant, Arkansas:

Looking for a way to feed your love and expand your knowledge of the great game of baseball? Check out the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR).

SABR was founded in the spring of 1971 when a baseball super-fan named Bob Davids sent a letter to about 40 other baseball fanatics around the nation to determine if there was interest in forming an organized group interested in searching for a “deeper understanding of the game.” Fifteen of those contacted met that summer in Cooperstown, New York, to organize the Society for American Baseball Research.

Since its humble beginning, SABR has grown to over 7,000 members worldwide, ranging from everyday fans to members who cover the game and to those who work in it.

SABR offers something of interest for every baseball fan whether your passion is baseball history or advanced baseball statistics or anything in between.

In the SABR Research Collection, members can browse 10,000 baseball images or listen to players in interviews in the Oral History Collection. Or read about more than 4,400 games in the SABR Game Project or any of the 6,000+ baseball figures in the Biography Project. Better yet, use SABR’s research tools and learn to do baseball research to make your own contribution.

Love to read? Members receive member research publications The National Pastime and Baseball Research Journal each year plus two special SABR ebooks (usually about a particular player, ballpark, or team) each year – and all previous publications can be downloaded by new members.

But perhaps the biggest SABR benefit is the relationships developed from meeting like-minded baseball fans.

In addition to the annual SABR National Convention and numerous research committees made up of members who share the same specific baseball interest, regional chapters meet regularly throughout the country.

In Arkansas, the Robinson-Kell SABR chapter was formed in 2004 and named in honor of Hall-of-Fame third basemen Brooks Robinson and George Kell.

The Robinson-Kell SABR chapter meets twice a year in Central Arkansas – August and February – with most meetings including an opening presentation by a former major or minor leaguer from Arkansas or a special guest with a baseball background. The guest speaker is followed by various member research presentations, mixed with baseball chatter and snacks.

The next scheduled meeting of the Robinson-Kell SABR chapter will be August 12, 2023, from 12:00 to 4:30 at First Southern Baptist Church in Bryant, AR. The address is 604 South Reynold Road. The meeting will be at the left end of the building when entering the parking lot. Snacks and soft drinks will be provided.

Our guest speaker will be Mark Tolbert, who as a kid in 1967 was the Atlanta Braves batboy during their second season in Atlanta. He has lots of stories to tell, including his interactions with Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

Following Mr. Tolbert, the following presentations will take place…………

· Kent Faught – Bad Management 2.0: How MLB Replicated the Nonsense of the Steroid Era with the Houston Astros Sign Stealing Scandal

· Ronny Clay – Mildred Earp of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League

· Jim Yeager – Discussions from his new book Hard Times and Hardball.

· Tom Van Hyning – Three Arkansans – Gene Bearden, Solly Drake, and Brooks Robinson – played in Cuba’s Winter League

· Johnny Mullens – Jerry Adair: Teammate of Eddie Sutton and Brooks Robinson.

Guests are not only welcomed, but cordially invited. For details of previous Robinson-Kell chapter meetings, visit the chapter website.

Meeting baseball fans and telling “Grandpa Stories”

We had a nice crowd at the White County Historical Society meeting last Monday in Searcy. Scott Goode and Johnny Mullens joined me at this event and spoke about the chapters they wrote for Hard Times and Hardball. Johnny’s chapter is about Johnny Sain’s invention of a pitching aide called the Johnny Sain Spinner. Scott is the Sports Information Director at Harding University, Preacher Roe’s alma mater. Scott’s chapter is an in-depth look at Roe’s “Harding Years.”

Saturday I signed books and talked baseball at Dog Ear Books with old friends and some new folks who love the game. If you live in the Russellville area and have not checked out Dog Ear Books’ new location, you need to visit soon. Grab a cup of Retro Roast, and see what kind of magic the Dog Ear folks have performed at their new and more convenient location. The new address is 312 W 2nd St, in Russellville. Russellville needs Dog Ear Books!

This week - The Bookish Emporium in Heber Springs - Saturday, August 5 Book Signing from 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM

Ohtani and Smead Jolley

Okay, I am continually impressed and often conflicted about Shohei Ohtani. I do wish we could read about him in the context of the here and now and baseball writers did not feel compelled to call him a “Future Hall of Famer.” As of today, he is batting .302 with 39 home runs, and an OPS of 1.083. He is the best hitter in baseball period. He is 29 years old and mostly a DH.

So, how does he compare with Big Pappi, the first real DH to be selected for the Baseball Hall of Fame? On their 29th birthday, Ortiz had hit 177 home runs, and Ohtani has hit 166 homers as of Saturday. On that 29th birthday, Ortiz had a career batting average of .282. Ohtani’s career batting average is .273. The two OPS marks are very close at age 29 (Ortiz, .901, and Ohtani, .917), but Ohtani has more work to do. Ortiz was at his best from age 30 to age 40. During those 11 years, he added 354 home runs to his lifetime total.

As a pitcher, Ohtani has 37 career wins, nine this year. Thus far in the 2023 season, he is 11th in ERA (3.43) and third in strikeouts in the American League. Once again he has work to do to be a cinch Hall of Famer based on pitching alone.

The most interesting piece of Sabermetrics is a Bill James math thing called the Hall of Fame Monitor. It attempts to assess how likely (not how deserving) an active player is to make the Hall of Fame. Using its rough scale, 100 means a good possibility and 130 is a virtual cinch.

David Ortiz had a career score of 171 as a hitter on the Hall of Fame Monitor. That score ranked him 67th all-time among hitters. Ohtani’s current score as a hitter is 41, a score that places him 535th as a hitter. As a pitcher, his HOF Monitor score of six ranks 1,384th among pitchers. These rankings mean nothing if Ohtani continues as both a hitter and pitcher at a similar pace for the next 10 years or so. Of course, there is no category for a pitcher/hitter like Shohei Ohtani!

But for now, he is some kind of fun to watch! Last Thursday, for instance, he became the first MLB player to pitch a shutout in the first game of a doubleheader and hit even one home run in the second game, much less two.

What if the DH rule was in place in 1930?

Reading and watching Ohtani has me doing a lot of thinking about the Arkansas guys who pitched and played in games as position players when they did not pitch. A few posts ago in this space, I wrote about an Arkansas pitcher/hitter named Jimmy Zinn, who was primarily known as a pitcher. Today, I am going to tell the story of one of my favorite “lost players” in Arkansas baseball history, a not-so-good pitcher who may just have been the most underrated player in the history of Arkansas-born professional baseball players. His name is Smead Powell Jolley.

Arkansas Hit and Miss Man

I know I wrote about Smead Jolley a few weeks back, but allow me to go back to a story of a forgotten guy who just might have been a darn good DH.

Smead Jolley played his last professional baseball game more than 80 years ago. Today, in a sport that loves its numbers; his name is seldom mentioned among the greatest hitters in Arkansas baseball history. Conversely, his detractors can defend a claim that he was one of the worst defensive major leaguers of all time. Those tales of inept defense are told much more often than his hitting accomplishments. The late Terry Turner, one of Arkansas’s most respected baseball historians, appropriately christened Jolley, “The Hit and Miss Man.”

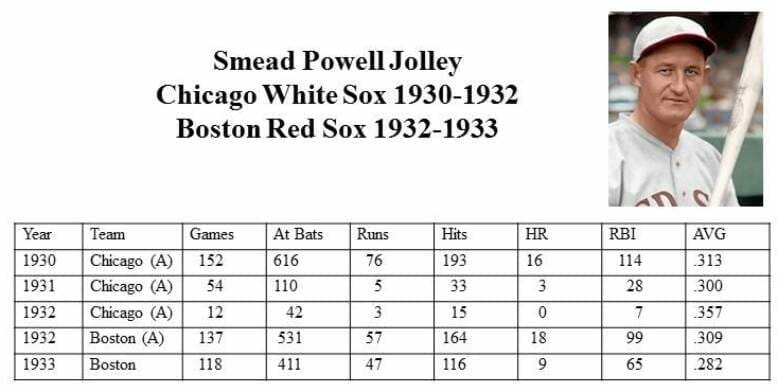

Jolley had a lifetime major league batting average of .305 and a career minor league batting average of .369, lofty marks by any standard. In a professional career that included more than 2,400 games in the majors and minors, Jolley hit more than 360 home runs and had a lifetime batting average of .357 for all professional games.

Smead Powell Jolley was born in Union County, Arkansas, in 1902, and grew up in the small community of Wesson. According to Jolley, he headed out on his own at about age 16, and by his late teens, he had found work in the oil fields in nearby El Dorado. The discovery of oil in 1921 had turned El Dorado from a quiet farming town into a bustling boomtown. Jobs were plentiful but difficult. Young Jolley soon decided he would rather play baseball than work at hard labor. “I was a better pitcher than an oil worker,” stated Jolley.

Jolley broke into pro baseball in 1920, as a 20-year-old pitcher, with Greenville in the Cotton States League. He continued to pitch with only moderate success for his first three years in pro baseball but he never failed to post a batting average above .300. It soon became obvious that Jolley’s future was as an everyday player. By 1925, he was a regular outfielder with Corsicana in the Texas Association, where he hit 26 homers and batted .362. At the end of Corsicana’s season, he was sold to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

The Pacific Coast League was an attractive place to play. The league was considered a small step below major league quality. Playing in a temperate West Coast climate, the PCL often played schedules of 200+ games from late February into November. Salaries were comparable to the major leagues, and with no competition from the stars of the eastern cities, the players were celebrities.

Many Arkansas-born players had their best years in the Coast League, and some of baseball’s all-time greats made their pro debut in the PCL. Yell County’s Bert Ellison was inducted into the PCL Hall of Fame in 2006. Joe DiMaggio started his career in Oakland, as a 17-year-old baseball prodigy, and Ted Williams played his first game in 1936 for San Diego in the PCL.

Jolley would play nine seasons in the Pacific Coast League, five in the 1920s, and four seasons in the 1930s, separated by a four-year stint in the major leagues. He hit .388 for the San Francisco Seals during his first five years in the PCL, including a remarkable .404 batting mark in 1928. In 1929, Jolley’s .387 average in 200 games, earned him a trip to the American League Chicago White Sox. He left the PCL with a pre-established reputation as a “hit-and-miss man.” One California writer described Jolley’s efforts in the outfield as “…like a child chasing bubbles.”

Jolley played in the White Sox outfield for parts of three seasons, batting .314 over his time in Chicago, but he failed to distance himself from the prevailing opinion that he was a liability in the field. Traded to Boston in the spring of 1932, he continued to be a consistent .300 hitter and a team leader in runs batted in. His batting marks, examined alone, indicated he would enjoy a long career in the big leagues, but his reputation as a poor outfielder clouded his profile and doomed his major league future.

Smead Jolley was not a good outfielder. Maybe “not a good outfielder” was an understatement to much of the late 1920s baseball community. The unflattering analysis of Jolley’s defensive skills could have also been a convenient exaggeration, unfairly attached to a somewhat limited outfielder, simply because it made a good story. Baseball’s past is filled with colorful stories, and there is no shortage of tales about Smead Jolley’s adventures in the outfield.

One of the most questionable incidents had Jolley patrolling left field for the White Sox in a game at Philadelphia against the As, or some say it was in Cleveland against the Indians. Another possibility is this sadly humiliating event never happened at all but is a combination of plays and embellishments that creates a tale too good to refute. Regardless of its accuracy, the story began when a sharp single hit Jolley’s way rolled between his legs as he attempted to field it. He turned to play the ball after it hit the wall, and it rolled back between his legs. By that time, the runner was headed for third. Jolley ran down the ball and threw it into the home dugout. The runner scored, and Jolley had the dubious distinction of making three errors on the same play.

The fact that a box score with three errors charged to Jolley on the same play can’t be found, doesn’t deter the story’s defenders. They simply explain that the official scorer took pity on the befuddled young fellow and only charged him with one error.

Although at almost 6’4” and somewhere near 220 lbs., Jolley was certainly not a gazelle in the outfield. He did, however, lead the league in assists by an outfielder in 1930. He also pulled off an unusual fielding feat typically performed by speedy outfielders, when on May 27, 1930, he recorded an unassisted double play while playing right field. Despite this evidence in his favor, Jolley was subjectively branded by managers as a poor fielder, capable of costing his team more runs than his good hitting could produce.

With Boston in 1933, Jolley saw his playing time significantly reduced. He played in 118 games and had over 160 fewer at-bats. His home run total plummeted to nine and his RBIs fell from 99 to 65. Boston was giving up on him, and the pervasive idea that Jolley cost a team more runs with bad defense than he produced at-bat had now become widely accepted.

December found Jolley part of a multi-team trade that ended with him being sold to Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League, where he picked up right where he left the PCL. Jolley hit .360 with 23 homers in 1934 and .372 with 29 home runs in 1935. The big country boy the fans knew as “Smudge” was a popular player for the PCL Hollywood Stars, and his hillbilly charm made him something of a celebrity in a city of celebrities. Jolley even got a bit part in the baseball movie, Alibi Ike, with Joe E. Brown and Olivia de Havilland.

Smead Jolley would play seven more minor league seasons after his demotion from the major leagues. Most of those games would be played in his adopted baseball home in the Pacific Coast League. His batting average was above .300 in each of the seven summers in the twilight of his career.

Smead Powell Jolley was a phenomenal hitter. Perhaps he was one of the greatest hitters of all time and certainly one of the premier sluggers of his era. Although his name will never be found among the baseball greats enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame., he was elected to the PCL Hall of Fame in 2003, and the Union County, Arkansas, Hall of Fame in 2013.

So, what if the DH rule was around in Jolley’s day to relieve him from his fielding duties? Perhaps the first DH in the Baseball Hall of Fame would be “Big Smudge” instead of “Big Pappi!”