Backroads and Ballplayers #16

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Book Tour, Coffee Shops, and a Cup of Coffee in the “Show”

“Book Tour” Update

We were busy last week with what we call our “book tour.” We started in Dardanelle with one of our favorite history groups, the Yell County Historical Society. We love these folks and they seem to like our old baseball stories.

On Saturday, we returned to a memorable location, the former home of Coach and Bears Dugout. About three decades ago, Billy Newton and I were partners in a sports card store here. That was back in the days before grading and gambling changed the baseball card hobby. We signed about three dozen books and made new friends along with seeing some of our special old ones.

This week we open at Searcy on Monday, July 24, at the White County Historical Society in Searcy. The meeting begins at 7:00 PM in the Carmichael Community Center at 801 S. Elm in Searcy. We will give a presentation about the days when “Baseball Was Arkansas Game” featuring the stories of White County’s colorful players who are part of our state’s baseball legacy. Guests welcomed.

On Saturday, July 29 from 9:30 - 11:00, we will be hanging out at the new location of Russellville’s hometown bookstore/coffee shop, Dog Ear Books. Dog Ear has moved to a new and easier-to-access location at 312 West 2nd Street, in Russellville. What could be better than a bookstore with a coffee bar? Please join me that morning as we browse through Dog Ear’s new digs, have some Retro Roast Coffee, and maybe sign a few books. Russellville needs Dog Ear!

This just scheduled: We are going to Heber Springs to the Bookish Emporium on August 5. Signing books at 10:00 AM.

“A Cup of Coffee” Scat Davis

Baseball breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart.

– Former Commissioner of Baseball Bart Giamatti

I guess I have seen “Field of Dreams” a dozen times, not counting the 100 times I have Googled James Earl Jones’ famous lines or video of Burt Lancaster’s poignant portrayal of “Moonlight” Graham as old Doc Graham in Minnesota.

Folks who are paid to tell us if we should like movies are lukewarm about the film from the summer of 1989. These experts used words like “sappy,” “overacted,” and “cliched” in their reviews. They commented on the awkward action scenes and remind us that in the movie the late Ray Liotta batted right-handed playing the lefty Shoeless Joe Jackson, but to those of us afflicted with the nostalgic romance of those baseball days, the movie was perfect. To tinker with James Earl Jones’ famous lines a little, “The memories were so thick we had to wipe them away from our faces.”

And yes, there was a real Moonlight Graham. He did play in one big league game, and he never came to bat. We had Arkansas guys with similar experiences.

A “Cup of Coffee” in major league baseball has become an unfortunate phrase that trivializes a very short big-league career. Of those brief big-league stays, a thousand or so men played only one game at baseball’s highest level. In approximately two dozen of these brief Cup of Coffee careers, the player did not pitch, come to bat, or play in the field. Those poignant biographies include one speedy young man from Charleston, Arkansas, and one ex-Traveler who made Little Rock his adopted home.

“Scat” Davis played in the major leagues, a dream for every boy who ever picked up a bat and glove. To those who dream the dream as youngsters, the length of their major league career never comes into question. In their dream, they play lengthy, distinguished careers filled with last-inning walk-off home runs or World Series no-hitters. In their dream, they bask in the adoration of loyal fans and become renowned superstars in the game they love.

For those fortunate enough to realize some variation of the dream, fulfilled by actually reaching the big leagues, the reality is often much less grandiose. These less distinguished major league careers are nonetheless treasured by former major leaguers. Each time at bat, or the simple act of trotting out to play in the field in a major league ballpark, is permanently recorded as a cherished memory. At least that is the case with almost every man who ever donned a major league uniform.

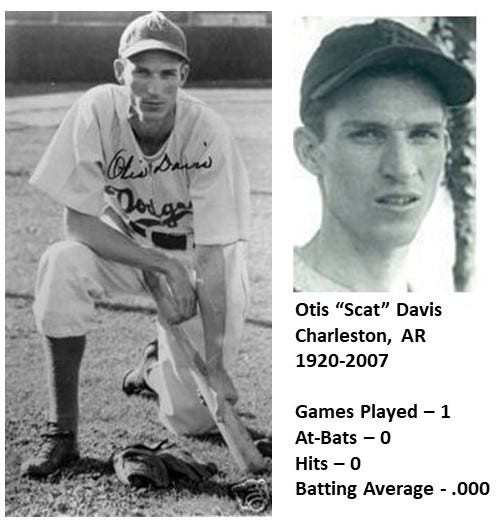

Otis “Scat” Davis was born in 1920 near Charleston, Arkansas. The son of a coal miner, he was born just in time for some of rural Arkansas’s toughest years. The Great Depression hit the rural South hard. Davis’ mother died in 1929, and his father struggled to feed five children as a single parent. Davis later recalled, in an interview with baseball historian Jim Sargent, that because he was needed to help support the family, it took him a few extra years to finish high school.

Otis Davis excelled in all sports at Charleston High School, and since baseball was the only sport that offered a way to play for money, he took a chance. After graduation, he found his way to the Ban Johnson Amateur League in the Kansas City area. Davis was playing with Maryville in the BJL in 1941 when the Cardinals discovered him and offered him a contract.

Scat Davis spent the 1942 season traveling the Cardinal farm system from Louisiana to West Virginia, and finally to Canada, where he finished the season. By late summer he was batting .281 in about 100 at-bats with Hamilton when the reality of the times came calling. In early August, like so many young men in America, he enlisted in military service with the US Navy.

Otis Davis could run. Early in his career, he had earned the nickname “Scat” because of his speed. His ability to run the bases well and chase down potential hits in the outfield was astonishing, considering he seriously injured his knee in high school. The knee was so bad, in fact, that the Navy soon granted Davis a medical discharge because his knee would not hold up in basic training. Before the knee repairs that are commonplace today, Scat Davis played his entire career with the troublesome knee.

Scat bounced around the Cardinals organization until he caught the National League team’s attention with a promising minor league season in 1945. By the close of the season, he had played more than 300 professional games and earned a good look by the Cardinals in 1946.

When the Cardinals left Florida for St. Louis after spring training in 1946, 25-year-old Scat Davis was on the train. Davis’ time in St. Louis was brief, however, and he never saw the field in the three games he sat on the Cardinals’ bench. A transaction notice ran in the sports pages on April 20, announcing Davis had been sold to the Dodgers the previous day for the minimum wavier price of $7,500.

Scat Davis arrived in Brooklyn to join the Dodgers while they were playing a weekend series with the crosstown New York Giants. Davis did not play in his first series in a Dodger uniform, but he made his debut on Monday, April 22nd when the Dodgers started a series with a day game against the Boston Braves.

Boston had built a 4—2 lead going into the bottom of the 9th inning. With some younger players in the lineup, Durocher still had some of his newly-returned war veterans on the bench. One of these veterans was Eddie Stanky, a crafty hitter, who had set a league record with 148 walks in 1945. Stanky would lead the league in walks again in 1946. And predictably, when called on to pinch-hit for the pitcher in the ninth, Stanky walked.

Durocher sent Scat Davis in to run for Stanky, to get a faster runner on base. Davis moved to second when another pinch hitter, rookie Bob Ramazzotti, also walked. With runners on first and second, future Hall of Famer Billy Herman fouled off two bunts before getting one successfully down to advance Davis and Ramazzotti. Davis raced toward third on all three bunt attempts. Unfortunately, on one of the 90-foot sprints and slides into third, he reinjured his bad knee. Davis stayed in the game and limped home on a double later in the inning, to send the game into extra innings.

When Boston failed to score in their half of the 10th, Billy Herman’s RBI single won the game for the Dodgers. Scat Davis had played in a major league game and taken part in the 9th-inning comeback. Although his knee was swollen and sore after the game, he had no reason to fear he had played his last major league game.

A few days later, it was obvious Scat Davis could no longer run on his bad knee. The Dodgers sent the rookie down to Montreal and later to Fort Worth to rehab his tender knee. After a handful of games for each minor league team, Davis knew his knee needed rest. He headed back to his adopted hometown of Rochester, New York, married in August, and settled into retirement from baseball.

A few months of retirement and enough rest for his knee to feel better convinced Davis to try pro baseball one last time, but he was never the same prospect. He bounced around the minor leagues for a couple more years, but he never got the call to return to the majors.

When Scat Davis was asked if he still had dreams about a different outcome, he answered, “Moonlight Graham played the field, but he never got to bat. I’d like to have batted, but I could have gone 1-for-1, or I could have struck out.” “Think about this,” Davis added about the opportunity to pinch run, “What if Eddie Stanky had struck out? If he doesn’t get on base, what happens to my shot at the big leagues?”

Robert Henry Mavis, Adopted Son and Pinch Runner

In the spring of 1946, Otis Davis was heading north with the Cardinals and would soon make his major league debut. That same spring, Wisconsin native, Bob Mavis, was moving his wife and young daughter to Little Rock, Arkansas, their new hometown. Mavis was beginning the third of five years with the Arkansas Travelers, the Chicago White Sox AA minor league team. Five years is a long time to play full seasons with one minor league club. He not only played with the Travs those years, he was outstanding. Mavis batted over .300 each year, and he led the team in several offensive categories in many of those seasons. Mavis loved Little Rock, Arkansas, and Arkansas loved him.

By 1949, after five excellent years in Arkansas, Mavis and the Travelers had become the property of the Detroit Tigers, and he was finally promoted to the Tigers AAA club in Toledo. He hit .300 again at the higher level and managed to hit 12 homers, a respectable number for a 5’7,” 150 lb. infielder. Mavis had earned his chance in the majors and when the Toledo Mud Hens’ season ended he got the call to report to the Tigers.

Mavis traveled with the Tigers throughout September but did not get into a game until September 17th, when he made his major league debut, on a Saturday, in historic Yankee Stadium. More than 40,000 fans inadvertently turned out for Mavis’ first game. In a situation not unlike Scat Davis three years earlier, Bob Mavis entered the game as a pinch runner with his team behind. Unlike Davis’ debut, however, Mavis’ appearance did not have a happy ending for his team. Mavis pinch ran in the top of the 9th for backup catcher Bob Swift, who had reached base on Phil Rizzuto’s error. A fly ball and a walk later, Mavis was on second, with a runner on first and one out, when Johnny Lipon grounded into a game-ending double play.

The Yanks had held on and were one step closer to the pennant they would clinch the next week. Bob Mavis was running to third base as the double play behind him ended the game. If Mavis had the benefit of present-day hindsight, he might have lingered a bit on third as the legendary Yankees trotted in for the celebration. If he walked slowly toward the dugout, Mavis could have passed Joe DiMaggio one more time, or if he stopped to tie his shoe, he could have taken another look at pitcher Joe Page hugging catcher Yogi Berra. Mavis could have locked in the sights and sounds of that personally historic day had he known he would never have another chance in a major league game. He was, after all, in the venerable old Yankee Stadium. The jubilant home crowd was on its feet, and he was walking off the field in the big leagues. Unfortunately, none of the cheering was for Bob Mavis.

Mavis would play six more years of minor league baseball and later get a brief chance to manage his beloved Arkansas Travelers. He retired as an active player in 1957 but continued to scout throughout the South for several major league teams. Bob Mavis had chosen to call Little Rock home during his playing days and remained there while working as a scout. He retired in 1990 after nearly a half-century in baseball. Mavis died in Little Rock in 2005, as one of the all-time Arkansas Traveler greats and a former major leaguer. According to Mavis, “I got a cup of coffee, but I never got any cream.”

Coming and going…

Frequent Flyer…

Last week former Razorback pitching star Isaiah Campbell was in Seattle as a member of the Mariners watching the All-Star Game as a big leaguer. Three days later he was on a plane back to Little Rock despite pitching 3 2/3 innings without allowing a run. After 36 hours, he was back in the air, reporting to the big club for at least the weekend. He was the winning pitcher for the Mariners Saturday despite his worst outing in four appearances as a big leaguer. Don’t unpack, Isaiah!