Backroads and Ballplayers #13

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Wrapping up the CWS, A Tribute to Drew Smyly and Gene Bearden, and some desk cleaning…

Tigers Geaux Big

It pains me to say the best team won what is apparently now called the Men’s College World Series. I can certainly live with that name change. Anyone who watched the Women’s College World Series and did not come away impressed by the skill level, intensity, and youthful spirit of those players and teams, was not watching the same event that I saw.

I have tried to rank the displeasure level of the result of the last three MCWS. It is difficult. I hear those annoying cowbells for hours after that team from Starkville is no longer on the field. I have at least as much disdain for those folks who want fans to help with memory loss. It goes something like, “Hotty Toddy, Gosh Almighty,” we can’t remember who we are… and now those rabid fans from Baton Rouge get the last dog pile.

I temper my discomfort with genuine respect. Each of those last three NCAA Champions came up big when it counted, and their fans invaded Omaha like an army capturing new territory. I guess “it just means more,” and most of my animosity may actually be jealousy.

Tennessee tried to go one up in fan attention early in the tournament by bringing in Peyton Manning. Who else would impress local fans? The Vols had the guy who made Oh-Muh-Haw an NFL by-word?

LSU saw the Vols’ celebrity quarterback and raised them one Social Media icon, a gymnast name Olivia Dunn. Although I confess to my Backroads and Ballplayers readers that I did not have a clue who “Miss Livvy” was and why the autograph line was about 90 feet long. Now I know, and publicly I plan to say I was familiar with the “Queen of Instagram” before the MCWS.

To add to the attention off the field, the somewhat unofficial LSU Jell-o Shot team arrived by the weekend. Sponsored in these NIL days by the founder of Raising Canes, the team from Red Stick dominated the bar scene. Wake Forest stayed with the more experienced team from LSU for a few days but faded after their team was eliminated on the field. Oral Roberts and TCU were on shaky ground with their school’s public mission and also dropped back after their team went home. The Tigers bar team eventually set a new MCWS record by consuming 68,888 of the $5 shots. A standard that will stand at least until some other SEC bar team arrives with a sponsor willing to publicly back their team to a new level. I just can’t see the Walmart Jell-o Shot team.

Now for credit where praise is so obviously due. LSU had a formidable lineup featuring the Golden Spikes winner, Dylan Crews, an unlikely-looking DH, Cade Beloso, who seemed to be able to hit any pitch, and a host of other clutch hitters. The Tigers also had college baseball’s best pitcher, Paul Skenes, and a strong supporting cast. When Florida was down to pitching their first baseman, LSU continued to run out effective arms in a deep pitching staff, and by the way, their coaching staff did an amazing job of managing their roster. Congrats to the Tigers.

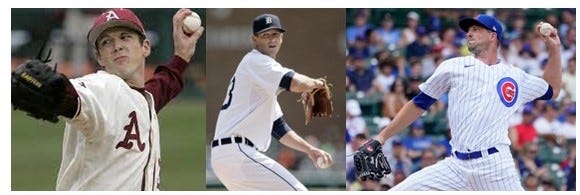

A Tribute to Drew Smyly

As of this writing, Drew Smyly has a lifetime record of 60 wins and 52 losses. His career ERA is 4.09 and in 10 seasons in the big leagues, he has never been an All-Star. A closer look at the double-certified Arkansas major leaguer, (born in Arkansas, and a Razorback hero) reveals one of our state’s most successful baseball stars, an oft-injured pitcher who never gave up and who produced a historic performance in one of the game’s most watched events.

On August 11, 2022, Drew Smyly emerged from a cornfield in Iowa dressed like Lon Warneke. The Cubs were playing the Reds in the second edition of the Field of Dreams game and Smyly was destined to be the lead story of the game.

Smyly’s record was an ordinary 4—6 as the Cubs’ fourth starter, but he had thrown six scoreless innings five days earlier. It was his turn in the rotation, but he would pitch far above modest expectations.

Although in-person attendance for Field of Dreams II was about 8,000 at a specially constructed ballpark behind the movie set, it was one of the most watched and highly publicized games of the 2022 season. Ken Griffey and Ken Griffey Jr. played catch before the game. Andre Dawson appeared through the corn, as did Barry Larkin, Ryne Sandberg, and Billy Williams. Ferguson Jenkins tossed the ceremonial first pitch to Johnny Bench. “Build it and he will come.”

When the game began it was Drew Smyly in the vintage uniform, but it could have been Cubs’ legends Lon Warneke, Dizzy Dean, or Mordecai “Three Fingers” Brown. Drew Smyly was dominating. No longer armed with a dominating fastball, he confounded the Reds for five innings, allowing four harmless singles and striking out nine. As he left the mound after five shutout innings the small ballpark in the cornfield rose for a standing ovation. Drew Smyly had been amazing on the game’s biggest stage.

Smyly had risen to be at his best at this kind of moment before, but more significantly, he had rejected many opportunities to leave the game and go home. He simply never gave up.

After graduating from Little Rock Central High in 2007, he missed his entire true-freshman year at Arkansas with a broken pitching elbow. Two screws in a pitcher’s elbow could indicate the end of a career, but after rehabbing the entire 2008 season, Smyly returned to the mound as a redshirt freshman in 2009. As a spot starter, he was 2—1 with an ERA near five when Coach Dave Van Horn called on Smyly to pitch the deciding game of the regional round of the baseball postseason at Norman, Oklahoma. All Drew Smyly did was hold the Sooners hitless until the eighth inning sending the Razorbacks to the Super Regional on the way to Omaha.

The following year, Smyly was the ace of the staff, posting a 9—1 record and a 2.80 ERA. After his outstanding 2010 All-SEC season, Smyly was drafted by the Detroit Tigers in the second round. By 2011, he was the outstanding pitching prospect in the Tigers’ minor league system. Smyly was named the Tigers Minor League Pitcher of the Year in 2011, posting an 11—6 win-loss record in 22 games with a 2.07 ERA and 130 strikeouts in 126 innings pitched.

Promoted to the Tigers in 2012, he was both an effective spot starter and a lights-out middle reliever in his first two seasons in Detroit before nagging injuries began to reduce his effectiveness. Over the next three seasons with Detroit and the Tampa Bay Rays, Smyly was 21—24 with a 4.67 ERA. His troublesome elbow problems ultimately resulted in Tommy John surgery in June 2017. It was a good time to return to Maumelle and help his father with the family restaurant, but that is not Drew Smyly’s style.

Had he not worked through the year-long rehab, Smyly would not have the World Series ring he earned as a member of the 2021 Atlanta Braves. (His 11—4 win/loss record led the team in winning percentage.) He would have missed the moment in Iowa when he was at his best and left the “Field of Dreams” as the winning pitcher…and he would have missed April 21, 2023, at Wrigley Field. On that Friday afternoon facing the Dodgers, 34-year-old Drew Smyly did not allow a runner to reach base until a swinging bunt in the eighth inning ended his bid for a perfect game.

As of this writing, his 2023 record stands at 7—5. Smyly is second on the Cubs in innings pitched and his ERA is a respectable 3.96. Drew Smyly remains the Arkansan with the most years of big-league service.

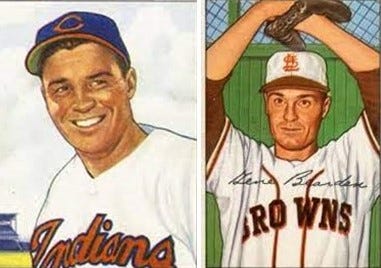

Gene Bearden’s Amazing Comeback

Drew Smyly’s story of determination and hard work is one of Arkansas baseball history’s most venerated stories, but there have been other Arkansans who overcame seemingly insurmountable setbacks to enjoy days of historic success. One of those was a war hero from the Delta named Gene Bearden. His finest hour occurred in a season 75 years ago.

In 2016, the once pitiable Chicago Cubs broke a seemingly unbreakable curse and won the World Series. The team the Cubs beat in that series, the Cleveland Guardians (Indians), now holds the dubious distinction for the most seasons without winning the World Series. Cleveland last won a championship in 1948, a 74-season drought.

The story of that remarkable 1948 season has the kind of plot we might expect from a movie with Kevin Costner playing the lead in a drama that ends with an unlikely victory. In the Cleveland story, the hero was a tall, lanky, knuckleball pitcher from the Arkansas Delta named Gene Bearden.

Henry Eugene Bearden was born in Lexa, Arkansas, on Sept. 5, 1920. Like many Arkansas boys in the 1920s, he spent his hot summer days with a fishing pole and a baseball. When Gene was 14, the family moved to Memphis. The country kid from across the river found himself out of place in the city. Fortunately for Gene, he was an exceptional athlete, and by the time he reached high school, he was a star in several sports. The story of a country boy who moves to town and becomes a popular sports star is not that unique, but Gene Bearden’s life was about to become the stuff of legends and a saga that features one of the greatest moments in Cleveland sports history.

Of course, there has to be a love story intertwined with the baseball story. Gene met the love of his life in Memphis. Lois Shea was a society girl who played piano, danced, and performed in stage productions for the Memphis in-crowd. Although they became some version of high school sweethearts, Lois and Lefty, as she called Gene, were from two different worlds. When Gene graduated, he had several offers to play college football and baseball, but the school part of college was not his thing. He enrolled in a baseball summer school in Greenbrier, Arkansas. Lois moved west to become a Hollywood star.

Gene was a first baseman when he arrived at Greenbrier, but the baseball school’s director, a country doctor named Earl Williams, convinced him that his future was as a pitcher. Eighteen-year-old Gene was the star of that summer school, and several major league teams sent scouts to the tiny Arkansas village to see the left-hander with the blazing fastball. With Doc Williams as his advisor, Gene turned down several teams to sign with the Phillies’ organization. Bearden was not an instant success in the minors, but he showed enough progress to be considered a big-league prospect until life got in the way of his trip to the major leagues.

America was at war, and Bearden, like so many young men, felt compelled to join the armed services. In mid-season 1942, he enlisted in the Navy. July of 1943 found him on the USS Helena in the Solomon Islands, instead of a major league ballpark. He was working in the engine room when the torpedo hit. Gene scrambled overboard and onto a raft where he drifted for two days before being rescued and taken to a Navy hospital, where he got the bad news. His knee was shattered, and he had also suffered a serious head injury. Walking of some kind was possible, but baseball was not.

He was eventually assigned to a hospital in Florida, where orthopedic surgeon Dr. A. F. Weiland recognized his name from his minor league days. Gene Bearden was in the right place at the right time. Using experimental and risky outside-the box-techniques, the surgeon repaired Gene’s knee and placed a metal plate in his head.

Gene’s luck was changing in more ways than a knee repair. His high school sweetheart, Lois Shea, could not get Lefty off her mind. In late 1943, she decided to find him. Through mutual friends, she found out the tragic news of Gene’s injuries and made phone calls to military hospitals until she found the right one in Florida. She would not lose Lefty again. Now a somewhat famous showgirl, Lois put her career on hold to support Gene’s comeback.

The comeback was phenomenal given Gene’s head injury and surgically repaired knee. He was released from the hospital in February of 1945 after almost two years of hospitalization. Miraculously, Gene worked his way into shape quickly and spent a remarkably successful 1945 season in the Yankees’ minor league system, where he met another key member of a support system that changed his life. In 1946, he joined the Oakland Oaks, a Yankee farm team managed by 55-year-old Casey Stengel. Stengel candidly advised Gene that his injuries had taken some velocity from his fastball and that he should rely on the knuckleball he was experimenting with at the time. The “Old Professor’s” instincts were correct, and by 1947, Gene got his shot with the Cleveland Indians. He pitched in one game and gave up three runs in less than an inning’s work.

Despite a disappointing outing in his only game in 1947, the 1948 season would be a sensational summer for Bearden. The rookie would produce the most dramatic pitching performance in Cleveland Indian history. Bearden got off to a good start, and by the end of July, his record was a respectable 8 – 3. A knuckleball doesn’t place a lot of stress on a pitcher’s arm, and as summer’s dog days arrived, and the Cleveland pitching staff began to wilt, Gene Bearden started his extraordinary stretch run. He won 11 games in the last third of the season and finished the regular season with a 19 – 7 mark, including three wins in the last week of the season. The Indians had come from five games back in early September to tie the Red Sox for the AL Championship. Although Gene had pitched a complete game two days earlier, he got the call from Manager Boudreau for a one-game playoff. Of course, truth is often stranger than fiction, and Bearden’s five-hit victory in the tiebreaker not only gave the Indians the pennant and his seventh straight victory but also a 20-win season.

The unfathomable story of the injured sailor-turned-hero continued in the World Series. With the series tied at one win each, Bearden faced only 30 batters and won a 2—0 shutout in Game Three. The two teams split Game Four and Game Five, and in the eighth inning of Game Six, Boudreau called for the knuckleballer to finish the game. Bearden came through, protecting a one-run lead in the ninth to clinch the series for the Indians. Teammates carried the rookie pitcher off the field. Gene Bearden was without question the man-of-the-year in Cleveland.

Like the Indians, Gene Bearden would never recapture the magic of 1948. He would pitch seven more seasons without a winning record in any of them. Bearden retired to Phillips County in 1958 and coached the American Legion team for many years. He was elected to the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1988. Bearden died in 2004 in Alabama, where Lois Shea Bearden lived until her death in 2006.

Cleaning My Desk

Dom is back in the show.

By now you may have heard that Dominic Fletcher is back in the National League with the Diamondbacks. The amazing twist of fate has him playing against his brother David this weekend in a series with the Angels.

Happy Independence Day

Once upon a time about two generations ago, this holiday was rural baseball’s biggest day. The Fourth of July picnic and community ball game was the highlight of the summer. The traditional baseball and picnic day featured lots of cold chicken and shade tree news sharing.

I can remember one of those. I guess I was about eight years old and Cass and Barnes, two North Franklin County community teams, met at the Barnes July Fourth Picnic. I remember the father of one of my third-grade classmates hit a ball into the woods in center field. I think his name was Let Conley and he seemed to my eight-year-old eye to be the local Mickey Mantle. It was probably a double, Let was in his overalls.

In those days, baseball was indeed “Arkansas’ Game.”

Click here to access previous posts.

Hard Times and Hardball is two weeks away!

I always enjoy these! Thanks, and Happy 4th!!

Great stuff, Jim!