Backroads and Ballplayers #12

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from the days when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Always free and always short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

The State of the Game, “Jittery Joe,” and a Book Plug…

It is fun writing about baseball history when such historic things are going on right now! The beauty of baseball is in the sum of its unique moments and its fascinating humanity. It is a game that not only allows time to think, plan, and grab a snack, it is also a game that explodes into flashes of split-second athleticism, raw power, and the joy of kids at play. There are elements of a game that thrive on contemplation and others that explode in uninhibited emotion. If you think baseball has outlived its value as a spectator sport you missed the hand-wringing in Omaha and the youngest player to hit for the cycle in 51 years.

Elly and Joey

Isn’t this Elly De La Cruz something? He is 6’5” and smiles a lot. He can run like a young Mickey Mantle, hit for power, and make all the plays at shortstop. In his last seven games, he had 15 hits in 30 at-bats, seven extra-base hits, and stole three bases. The once-forgotten Reds went 6—1, and now lead their division.

De La Cruz is 21 years old, and the day he hit for the cycle, his 39-year-old “written-off” teammate, Joey Votto, hit two home runs. It was one of those unique baseball things with explosive action and inescapable humanity. Yes, hitting for the cycle is the ultimate action sequence, but Votto is a compelling human-interest story. He hit his first home run when Elly was five. He had rotator-cuff surgery at age 39. Perhaps shoulder surgery was a good time to quit for a guy that has made about a quarter of a billion dollars playing a kid’s game, but here he is, trying to stay in the game. Votto is beginning to look like a first-ballot Hall of Famer and last week some fired-up Cincinnati writer surmised he is the greatest Reds’ player of all time. Hard to imagine that anyone not of the “Big Red Machine” would hold that distinction, but he has played his entire career in Cincinnati and the city loves him.

Jittery Joe Berry, Loved the Game… and Needed a Job

Joey Votto does not need a job. He has earned enough from baseball for his descendants to live comfortably for generations. He obviously still thinks he can play and that love of the game often overrides all financial logic. Some Arkansas-born major leaguers may have had that same affection for baseball and certainly had less financial independence.

On Sunday, September 6, 1942, at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, the Cubs and Pirates played a game that meant nothing. The Pirates were headed for fifth place in the National League standings, and the Cubs would finish one spot lower. America was embroiled in a war overseas and many major leaguers were already in the military. Teams were getting desperate for pitching. So much so, that on that day Cubs’ manager, Jimmie Wilson, decided to take a look at the unusual rookie the Cubs had added a few days earlier. Behind 3—0 and going nowhere in the standings, perhaps he was more curious than hopeful about this strange-looking fellow in his bullpen.

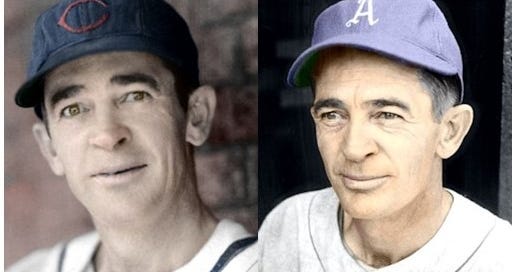

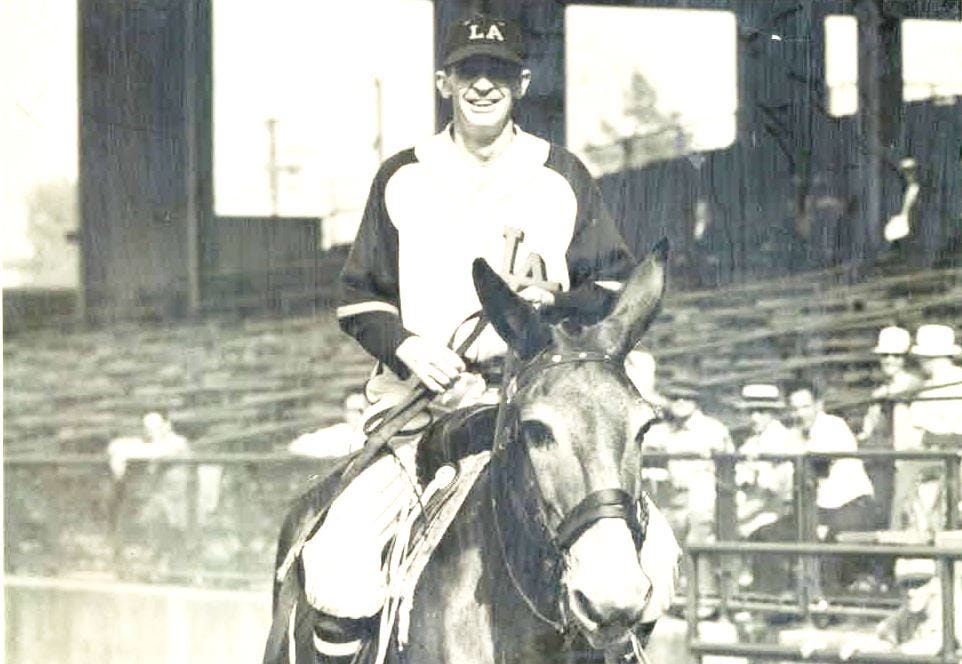

They called him “Jittery Joe,” and his appearance did not exactly strike fear in opposing hitters. The rookie pitcher was maybe 5’ 9” and on a good day weighed about 135 lbs. His uniform hung from a wiry frame like a child in an adult’s shirt, and his county stride walking to the mound was almost comical. Jittery Joe had been dominating for Tulsa in the Texas League in the 1942 season, but it took considerable imagination and some apathy for a major league team to give him a shot. Incidentally, Jittery Joe was 37 years old, and he had pitched more than 3,000 innings over 16 seasons to earn this chance.

Jonas Arthur Berry was born December 16, 1904, in Huntsville, Arkansas, in the heart of the Ozark Mountains. He was the eighth of nine children who grew up on War Eagle Creek, in Madison County. His father Jonas “Joan” Berry was a part-time farmer and occasional Sheriff of Madison County, having been elected to three terms over a forty-year period.

Known locally as Joe, Berry was a semi-pro pitcher of some notoriety in the Ozarks, when he got a chance to give professional baseball a try. He made his pro debut in 1927 pitching in Mississippi for teams in the Class D Cotton States League. He would remain with various franchises in the CSL for six seasons and post 85 victories during his stay in the virtual obscurity of baseball’s lowest minor leagues.

Berry was 28 years old before he advanced to Joplin in the Class C Western Association in 1933. He was the second oldest player on the Joplin team, which was not a good sign for a pitcher on the way up.

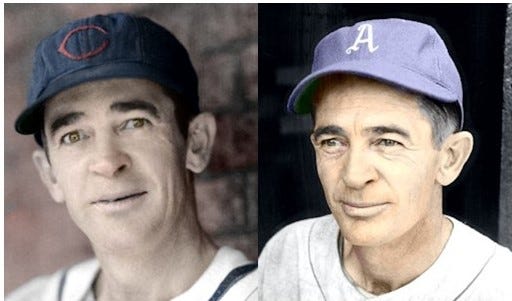

After three successful years in the Western Association, Berry got the promotion that changed his life in the winter of 1935, when the Cubs optioned him to the Los Angeles Angels of the prestigious Pacific Coast League. Big city newspapers covered PCL games daily, and sportswriters soon started searching for adjectives to describe the Angels’ unlikely-looking pitcher from the Ozark Mountains.

Always painfully slow-working, Berry became even more deliberate as his success began to depend more on deception than speed. He stepped off the mound, rubbed down the ball, tugged at his oversized uniform, and shook off the sign. Making the hitter wait was an effective new weapon. The term jittery seemed to fit him well, and by September most sports page stories about Joe Berry used his new moniker, “Jittery Joe.” Other new adjectives were also attached to Berry in the PCL. Many of these descriptions like “sensational” and “outstanding” had seldom been used to describe relief pitching before.

In 1942, despite six good years in Los Angeles, the Cubs moved 37-year-old Berry down to Tulsa, a Class A team in the Texas League, where he had another outstanding season. With hundreds of major league pitchers called to active duty, the Cubs were now so desperate for pitching help that in September Jittery Joe Berry got the call to the major leagues.

The game Jittery Joe had looked forward to for 17 years did not go well. After a routine first out, Berry gave up a double, a triple, two singles, and a walk. When the Pirates finally went down in the inning, Berry had faced eight batters, allowed five to reach base, and given up two runs. A week later he gave up two more runs in an inning’s work. He did not look like a major league pitcher, and he had not done anything to dispel that image.

The Cubs saw nothing of value in Jittery Joe and released him after the season. He was nearing his 40th birthday, but there was no quit in Joe Berry. Back in the minors with Milwaukee, he won 18 games in 1943. Berry looked good enough to Philadelphia Manager Connie Mack to get another shot at the majors. Perhaps the old Philly boss was desperate for pitching or perhaps he had a different perspective on age since he had just turned 81.

The 1944 Athletics finished a distant fifth, but Joe Berry was the best relief pitcher in the American League. He was second in the league in pitching appearances and the league leader in games finished and saves. Although finishing games and carrying the designation of “closer” had not gained the prestige of that role in today’s game, Joe Berry was an overnight star in Philadelphia.

In 1945, Berry picked up right where he left off in 1944. He led the league in games pitched and games finished. Despite the addition of a promising rookie third baseman from Swifton, Arkansas, named George Kell, the A’s were a hapless last-place club, with only one pitcher with more wins than losses, Jittery Joe Berry.

Jittery Joe’s size, age, and everyman appearance made him a Philadelphia hero and a national phenomenon. America needed “feel good” stories, and it was easy to enjoy the success of a 40-year-old hillbilly humbling the big guys up in Philly. Jittery Joe thrived on an assortment of deceptive slow stuff. Along with a screwball and an assortment of curves, some say he threw an occasional illegal spitball. If indeed he threw the spitter, he used the phantom spitball much more often. Along with his jittery antics, Berry would appear to go to his mouth, then to the ball, in an attempt to convince the hitter the spitball was coming. After those obvious tip-offs, it never did.

Berry had one more year in the majors in 1946, but with the regulars back from the war there was no place in the majors for 41-year-old Jittery Joe. He would continue to pitch in the minors for five more summers. He worked in more than 130 games after his major league career ended and his ERA for those seasons was a very respectable 2.93. He retired after the 1951 season at the age of 46.

A look at Jittery Joe Berry’s career gains some perspective in relation to 25 years of baseball’s legendary stars. When Berry broke into baseball in 1927, Babe Ruth was in the process of hitting 60 home runs for the legendary “murderers row” Yankee lineup that also included a 24-year-old kid named Gehrig, who drove in 173 runs. Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron had not been born.

Berry pitched against Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, and Ted Williams. He was almost twice the age of fellow Arkansan George Kell when they were teammates in 1944. He witnessed history from 60 feet away, pitching to Jackie Robinson in Canada in 1946, and when Berry retired in 1951, Mantle and Mays were rookies taking New York by storm. Ruth and Gehrig were deceased.

Jittery Joe Berry pitched in 936 games in 24 summers of professional baseball. He played on teams in 20 cities and towns across the United States from Laurel, Mississippi, to Los Angeles California, and he has the rare distinction of having played pro baseball in four decades from the 1920s to the 1950s. Jonas Berry lost his life in a traffic accident in Anaheim, California, on September 27, 1958, at age 54. He is buried in Huntsville, Arkansas, under a gravestone inscribed “Jittery Joe Berry.”

It Just Means More…College World Series Update

As this post goes live we still do not have a Division I NCAA Baseball Champion, but the 2023 CWS has already been a classic. I will share my thoughts next week.

Another Book Plug

It looks like my new book, Hard Times and Hardball will be live the weekend of July 15. It contains 67 chapters and 418 pages. It will sell for under $20. That is as inexpensive as I can publish a 400-page book while still trying to produce a professional-quality project that reflects the value of the story of Arkansas’ baseball heritage. More next week.

I you missed an earlier post you can access them all at this link.