Backroads and Ballplayers #112

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Sonny Gray, Pitching a Maddux, Bad Luck Part III: The War Years: Havana’s Johnny Sain, and Fort Smith’s Hank Feldman

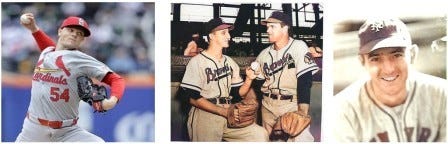

Pitching a Maddux- Sonny Gray

Cardinal fans, did you miss Sonny Gray’s masterpiece last week? You did if you were a FanDuel subscriber. It was not only a “Maddux,” which allows 99 pitches to qualify; Gray needed only 89.

Gray’s one-hitter was the third of these exceptionally rare pitching feats in 2025. A “Maddux” is a complete game shutout pitched on fewer than 100 pitches. The term is named after Hall of Fame pitcher Greg Maddux, who accomplished that amazing feat 13 times.

So far this season, Nathan Eovaldi pitched a Maddux in April, and the almost unhittable Tarik Skubal posted one in May. Actually, Skubal may have a tough time with the “complete game” part of the qualifications. His Maddux in May brought his CAREER complete game total to one!

Now that he pitches for the Cardinals, I love to watch Sonny Gray. He looks like an athlete, a golfer maybe, or a soccer player, but not a power pitcher if a strikeout pitcher looks like Tarik Skubal.

I have gotten over Gray being a Vanderbilt guy, but I am troubled that Kade Anderson looks like a lefthanded version of Sonny. I will work on accepting that!

The “complete game” part of the qualifications makes a Maddux even rarer in this era of pitch counts, long relievers, and concerns about arm health. So far, there have been 18 complete games in 2025. There were 28 complete games in 2024. Arkansas’ Johnny Sain pitched 28 himself in 1948.

____________________

A Subscription sends these weekly posts to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

_____________________

Pitching in the War Years - Bad Luck Part III or was it Good Luck?

John Franklin Sain

Johnny Sain had won four big league games when he entered military service in 1942. He had pitched fewer than 100 innings in the majors, and his career ERA was about four runs a game. He would miss three seasons. Was that bad luck?

Sain came back from military service in 1946. During the seasons he was in the military, he somehow became one of the best pitchers in the game. Was his time away from the major leagues good luck? What happened in those three seasons away from pro baseball? In his first season back, he won 20 games, posted a 2.21 ERA, and pitched 265 innings.

Earlier, I mentioned Sain’s amazing 1948 season. It was a career year for the curveball savant from Yell County, Arkansas. Sain led the National League in wins (24), games started (39), complete games (24), and innings pitched (314.2). He was a key part of the "Spahn and Sain" pitching duo, and the pair's dominance inspired the famous baseball rhyme, "Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.” Sain finished second in the National League MVP voting that year and was named The Sporting News Pitcher of the Year.

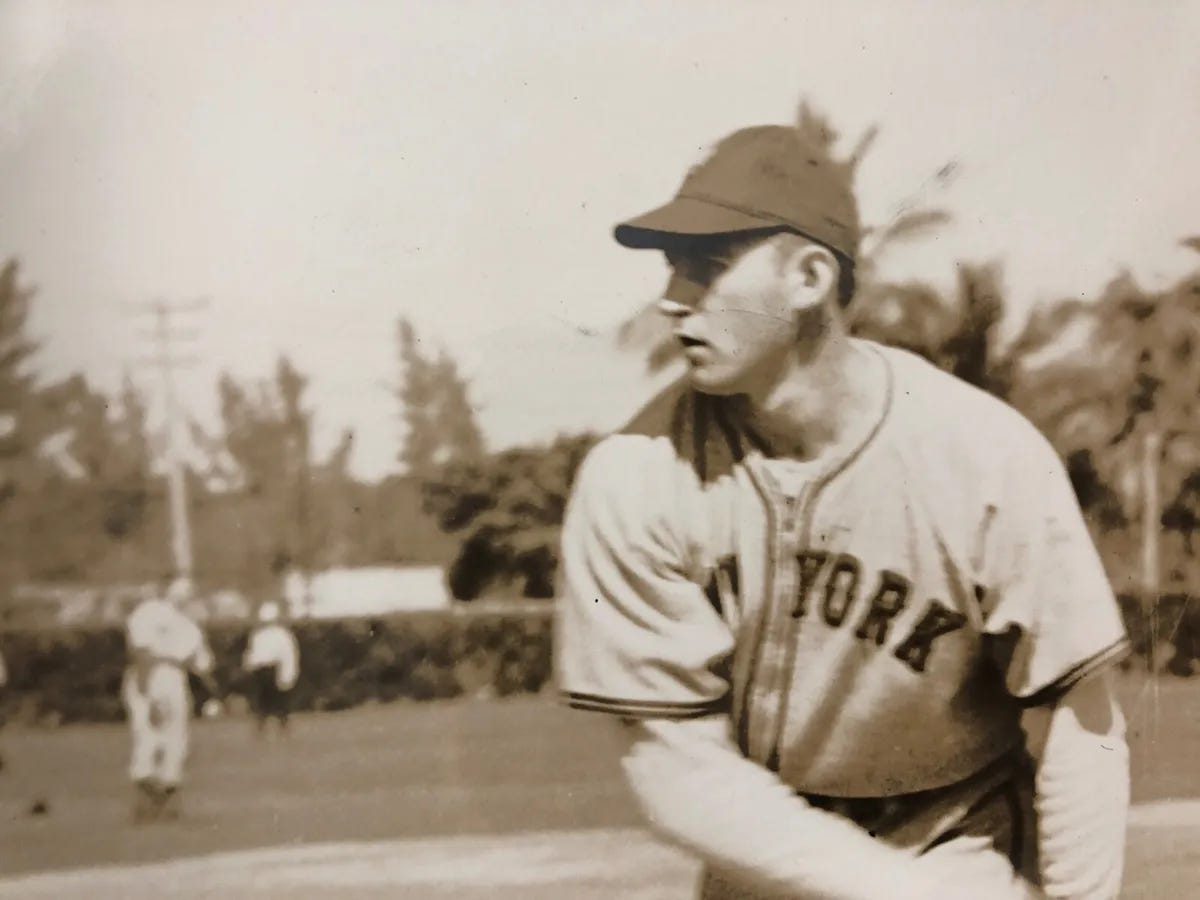

Harry Feldman

When the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the US into World War II, hundreds of professional baseball players joined the military or were drafted by their local draft boards. Harry Feldman, a New Yorker who had adopted Fort Smith, Arkansas, as his hometown, was exempt. Feldman had spent time in a tuberculosis sanatorium. Declared unfit for military service, Feldman became a starting pitcher for the New York Giants. Was that good luck?

A Trip to Elmore’s Record Shop

In the late 1950s, I received what we called a “record player” as a Christmas gift. I still have the stack of 45rpm records in my office. My parents liked Elvis. We had seen him on the Ed Sullivan show, and despite the disapproval of some of the older generation, my folks were all in for Elvis. That made it easier for an 11-year-old to buy a new record.

We raised a few calves on West View Mountain, and Dad always took me with him to Moffett, Oklahoma, to the Fort Smith Stockyards. I never asked why the Fort Smith Stockyards were in Oklahoma.

On the way home, we stopped by Elmore’s Records on Rogers Avenue. I could pick a 45 record. If the calf sale went well, I could choose two. Somehow, I knew one needed to be Elvis’ latest release.

The owner of Elmore’s was easily identifiable. He was an older guy (maybe 40) with a teenage haircut and the sleeves of his white shirt turned up a couple of rolls. His name was Hank, and although he looked like the owner of a record store, I never guessed he was once a major-league pitcher.

In the late 1930s, Harry Feldman was a Jewish kid growing up on St. Ann’s Avenue in the heart of the Bronx. The youngest son of immigrants, Morris and Edith Feldman, Harry was the most gifted athlete in the neighborhood. Good enough to be offered a pro basketball tryout, Feldman preferred baseball and the New York Giants. When the Giants offered the young pitcher a contract after a tryout, he jumped at the chance without fear of the culturally foreign land where he might be assigned.

The 1938 Giants held spring training at LSU’s home field in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. After about a month of practice and evaluation, the minor league prospects received their assignments. Some were sent home. The most advanced, who did not make the major league roster, would be headed for Jersey City, New Jersey—close enough to New York to be promoted quickly. Others would head to a Class B team in Richmond, Virginia, or a Class D club in Milford, Delaware. Two groups of younger prospects were headed for Arkansas—a Class C group to Fort Smith and a Class D squad to Blytheville in the Northeast Arkansas League. Harry Feldman was going to Blytheville.

Most of the Blytheville group were prospects the Giants had found in the northeast. Several, like “Hank” Feldman, were from New York City. Although many of Feldman’s teammates spoke his version of English, manager Hershel Bobo from Austin, Mississippi, might have needed an interpreter. Blytheville, Arkansas, was 1,000 miles from the Bronx in actual distance, but the small delta town was a foreign country for Harry Feldman and his teammates.

If the big-city youngsters assigned to Blytheville were suffering from culture shock, they did not show it on the field. The Blytheville Giants dominated the Northeast Arkansas League, and Hershel Bobo obviously found a way to communicate.

Hank Feldman topped all the loop’s hurlers in winning percentage and ERA. The Giants finished seven and a half games ahead of the second-place team and won the postseason playoff over Newport three games to one.

Hank Feldman won 13 and lost one before his promotion to Fort Smith on July 11, and he added seven more pitching wins in Fort Smith. For the two teams, his record was 20–8 with a combined ERA of 2.80.

Reassigned to the Fort Smith version of the Giants again in 1939, Feldman was instrumental in another pennant-winning season. He led the team in every major pitching category. Working in 40 games, Feldman pitched 276 innings, winning 25 games and losing nine.

While a member of the Fort Smith Giants, 19-year-old Feldman met a local teenager who was destined to be his wife. He and Lauretta Myatt would marry before the 1941 season and make their off-season home in Fort Smith.

Feldman spent the 1940 and 1941 seasons in Jersey City but struggled to maintain the success he had enjoyed in Class C. In two full seasons, he won 19 and lost 29 with an ERA that approached four runs a game. Although he did not post the excellent numbers he had produced in the lower minors, the Giants promoted Feldman to the National League club in September of 1941. He pitched in a no-decision start on September 10, tossed a complete-game shutout 11 days later, and lost a decision to Boston on September 27. He would remain with the big-league Giants for the next five seasons.

He had an excellent rookie year in 1942, winning seven and losing only one decision, despite spending part of his summer in the tuberculosis sanatorium. Feldman did not become a member of the Giants’ starting rotation until July. Getting stronger as the season entered its final month, he won his last five decisions. Although Feldman finished the season pitching well, the Giants finished a distant third.

Over the next three years, the Giants never finished higher than fifth, and Feldman had a losing record each season. His record was deceiving. He pitched more than 200 innings in 1944 and 1945. He won 12 and lost 13 in 1945, pitched three shutouts, and had 10 complete games in 30 starts.

Like hundreds of professional baseball players at all levels, the 1946 season was destined to be a challenging transition for Harry Feldman. He had been a mainstay on the Giants’ pitching staff since arriving in 1941, but with hundreds of players returning from military service, his recent performance did not guarantee him a job for 1946.

Feldman optimistically announced that the Giants had given him a “substantial” raise for 1946, but he reported for spring training with trepidation. The first full season after the war was a new beginning for minor leaguers who served in the military, and a hopeful return for former big leaguers. For many of the men who played in the majors during wartime, it marked an end to their big-league careers.

On April 1, an AP article reported that Feldman was on something called the “Ailing List.” Although the report indicated that he was expected back in action soon, when the season opened, he did not get off to a good start.

In the Giants’ third game of the season on April 18, Feldman gave up five runs to the Dodgers in two innings of work. Five days later, in Philadelphia, he was charged with three earned runs in the first inning and was relieved with only one out. On April 25, he pitched in relief against the Boston Braves and gave up a run in an inning and 2/3.

Feldman pitched a total of four innings in April of 1946. He lost two pitching decisions and recorded an ERA of 18.00. Unwilling to accept the inevitable demotion of a minor league assignment, Feldman gave up his “substantial raise” for a more lucrative offer in the Mexican League.

In 1946, in America and in the world of major league baseball, there was very little sympathy for the players who “jumped” to the Mexican League. The teams held all the cards. There were plenty of players available, so salaries were stagnant. Fans liked the idea of the reserve clause that bound their favorites to their chosen team, and $10,000 a year to play a boy’s game sounded like a pretty good deal.

With public opinion on his side and big-league owners unanimously in his corner, Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler suspended for five years those players who had defected to the Mexican League. In Chandler’s words, “The question was having the penalty severe enough so that it would deter fellas who might want to do the same thing for quick money . . . I just made it five years and stopped a whole lot of them.” Among those banned was Harry Feldman.

After going 0–2 with the Giants, Feldman reportedly lost 12 of his 13 decisions with Vera Cruz in the Mexican League. Although he was only 26 years old, Feldman was not the effective starting pitcher he had been previously. Was there more to the “ailing list” story, or had the 400+ innings over the last two seasons taken a toll on the iron man of the Giants’ staff? Regardless of the contributing factors, Hank Feldman’s career in major league baseball was over.

The results of his defection were not all negative for Feldman. The $15,000 bonus he received for his year in Mexico allowed him to buy a home in his adopted hometown. Major League Baseball would ostracize him for signing with the Mexican League, but Fort Smith, Arkansas, permanently welcomed one of its most beloved adopted sons.

By 1949, Commissioner Happy Chandler’s support for the suspensions had deteriorated. Lawsuits by the former Mexican Leaguers and prevailing public opinion that the player had been punished enough led the commissioner to end the expulsion.

Some players returned to the major leagues, but it was too late for Harry Feldman. He was able to find a job for the 1949 and 1950 seasons pitching for San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League. In 1950, his last pro season, he worked 230 innings and pitched in a team-high 46 games. The next year, with no chance of a promotion, Feldman became a year-round citizen of his favorite city, Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Looking for a business in his chosen hometown, Feldman fortuitously bought a record store in the early 50s. During the music boom brought on by the arrival of Rock-and-Roll, Elmore’s Records became a teenage hangout, and Feldman became a successful businessman.

During his years in Fort Smith, Feldman was an ardent supporter of the city’s youth baseball programs. An award created in his name honors the Fort Smith Church League player who “Displays the best Christian attitude, sportsmanship, ability on the field, and contributions to the Church League.”

Harry Feldman died on March 16, 1962, while on a fishing trip to Oklahoma. He was 42 years old. Johnny Sain remained in baseball as a pitching coach for two more decades.

In the late summer of 1963, my Babe Ruth team was runner-up in the Feldman League Invitational Tournament in Fort Smith.

_____________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link

Absolutely a gem of a story about Harry Feldman. Also, in the fall of 1976 I enrolled at Arkansas Tech University and quickly became friends with a fellow named Randy Sain from Walnut Ridge. Yep, it was Johnny’s son. Well done, Jim!