Backroads and Ballplayers # 104

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

The Hogs are Back? More on the AIC, and a New Mystery Photo

Hog Wild in Fayetteville…

If you predicted the Razorbacks would dominate Texas last weekend, please raise your hand. If you are a sports bettor, had money to risk, and were influenced into action by Joe Klein and the boys, have fun in Hawaii.

And…if you knew Zach Root was really Randy Johnson, send me your story.

Last week, I mentioned that the Texas series seemed like a big weekend for the Razorbacks. That statement did not take much research. Without a quality start since the Vanderbilt series in March, Van Horn, Hobbs, and all of us who thought the sky might be falling were looking for pitchers. Did we find five?

Root, Gage Wood, Gabe Gaekle, Will McEntire, and Aiden Jimenez pitched 18 innings, gave up one earned run, and struck out 29. That kind of pitching will win the rest of the SEC games!

Was it real? Only time will tell. Was it fun? It was more than fun; it was a rekindling of the hope we had a month ago. Go Hogs.

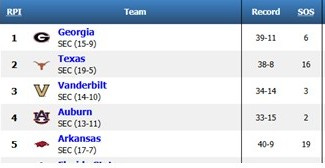

The Mysterious RPI

By the way, beating the number one team in the RPI three times moved the Hogs from fifth to…drumroll…FIFTH. Arkansas’ record against the teams above them in the RPI is 7-2.

It all makes sense to someone, and it seems to be important. In the last game of the Texas series, the broadcast crew theorized that the SEC standings meant very little; what is important is the RPI. Well, there you go. Who knew?

Now the Hogs parachute into Russia (Baton Rouge) and face a team ready to be the next underdog on a mission.

____________________

More thoughts on the AIC

Apparently, many of you over 60 have fond memories of the Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference. Realistically, the AIC was a football, basketball, and track conference. Baseball was almost a burden, despite being the “Great American Pastime.” The cold weather, lack of rainproof facilities, and budget constraints made baseball a “minor” sport.

AIC: First (Best) and Last AIC Alumni in the Show

While Baseball Reference.com seems to indicate that the first AIC player in the majors was Elwin “Preacher” Roe, the most successful major leaguer from the Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference, is unquestionably the lefty from Viola.

Elwin Charles Roe was born in Fulton County, Arkansas, in 1916. He grew up in the yet-to-be-incorporated town of Viola. Elwin’s fondness for an amiable local minister led to his nickname for life.

The story goes that when Elwin was a toddler, he was asked to introduce himself to a guest. Obviously influenced by his friendship with the minister, he proudly stated his name as “Preacher” Roe.

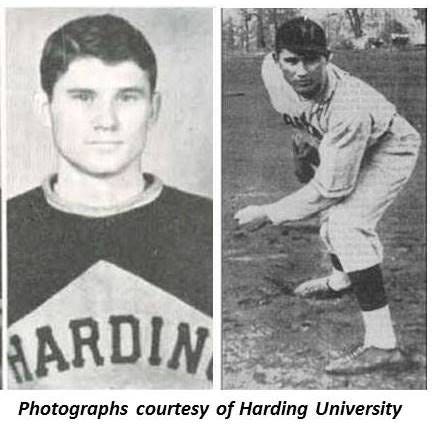

By his late teens, the tall, rail-thin, left-handed pitcher was the talk of North Arkansas. His father, Doc Roe, relinquished his spot on the mound to young Elwin, but the practical and cautious country doctor wasn’t ready to send Preacher off to a career in baseball. Roe yielded to his father’s advice and enrolled at Harding College in the fall of 1934.

Preacher Roe and his brother Roy soon became stalwarts on the Harding basketball squad. Although baseball was Preacher’s best sport, college baseball was an afterthought at Arkansas colleges during the late 1930s. The Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference was lukewarm on baseball. Members occasionally fielded a team but often dropped the non-revenue-producing sport played in cold, wet Arkansas springs.

Preacher Roe changed that perception drastically in April of 1937 when he struck out 26 Arkansas Tech batters in a thirteen-inning game. Scouts and sportswriters quickly found Harding College on the map, and Preacher Roe, the left-handed strikeout wizard, was national news from coast to coast. In a follow-up interview, Roe stated it was not his best strikeout game. The summer before, in the Pope County League, he had fanned 19 London, Arkansas, hitters in a nine-inning game.

In the summer of 1938, after another spectacular college season, Roe returned to semi-pro pitching and turned down the numerous offers to become a pro. In late July, he finally relented, perhaps because the St. Louis Cardinals, North Arkansas’ beloved favorites, were now in the mix, or perhaps because the $5,000 bonus looked too good to turn down, Preacher Roe signed with the Cards on July 25, 1938. The Cardinals had won the signing battle for a pitching prospect the press called “the Bob Feller of college baseball.”

The Cardinals ordered Roe directly to St. Louis, and less than a month after his signing, he made his very unpromising major league debut. Roe got the call in a Monday afternoon game on August 22, 1938, against the Cincinnati Reds.

Roe pitched 2 ⅔ innings, faced sixteen batters, and allowed half of them to reach base. He gave up six hits, two walks, and four runs. The Cardinals were forced to accept the reality that the National League was an all-too-hasty promotion for a country pitcher who had dominated the London town team and Arkansas Tech. Two weeks later, St. Louis traded him to their minor league club in Rochester.

Roe spent five unremarkable years touring the St. Louis minor league system before the Cards gave up on their once-promising lefty and traded him to Pittsburgh. With players in short supply because of World War II, the Pirates gave Roe a major league shot in 1944.

It looked like St. Louis had been hasty in discarding Roe when he posted winning records for both the 1944 and 1945 seasons. An unfortunate off-season incident changed that optimistic perception quickly.

Preacher Roe, like many rural Arkansans major leaguers who came before, played the expected role of uneducated hillbilly throughout his career. In reality, he hardly fit the stereotype. Roe had a teaching certification and spent winters teaching math and coaching back near his Arkansas roots.

Ironically, after he had finally established himself as a major league pitcher, his offseason work nearly cost him his career and his life. In January of 1946, Roe was coaching basketball in Hardy, Arkansas, when an angry referee threw a punch at the unsuspecting coach and toppled him into a steel railing. The injury sent Roe to the hospital diagnosed with a “skull fracture.” It would take weeks in the hospital for Roe to recover, but years to regain his pitching form.

When Preacher Roe reported to the Pirates for the 1946 season, he was not the same pitcher, and he was most certainly not pitching in the same league. The major leaguers who had served in the war were now back in their baseball uniforms, and the level of competition was significantly more challenging. The life-threatening, off-season injury had necessitated a lengthy hospital stay and left Roe several pounds lighter and less able to throw a fastball past the better hitters. These factors combined to make 1946 the first of two frustrating seasons. Roe pitched only 70 innings in 1946, in ten starts and eleven relief appearances.

The 1947 season was statistically worse. He upped his innings pitched to 144, but his ERA spiraled to 5.25 and his won-loss totals deteriorated to 4-15. Preacher Roe had one of the worst pitching records in the National League.

In the bleak days of the summer when things looked darkest, Roe found an ally in the Pirate bullpen. The Pirate backup catcher was an eighteen-year veteran named Al Lopez. Lopez, a future Hall of Famer and successful manager, knew the game, and he knew the strategies of successful pitching.

Lopez stayed with Roe in the bullpen after games, working for hours with a determined student who had no fastball. It would take a complete makeover for Preacher Roe to be successful again, but somehow he reinvented himself. In the summer of 1947, it was unimaginable that his best years were ahead.

In December of 1947, the Pirates gladly traded Preacher Roe and slick fielding 3rd baseman Billy Cox to the Dodgers for all-star outfielder Dixie Walker. Walker was a fan favorite in Brooklyn, but his best days were behind him. Despite the Dodger fans’ temporary unhappiness, the trade was another brilliant move by perpetually shrewd general manager Branch Rickey.

By the time Preacher Roe arrived in Brooklyn, his baseball life was more than half over. His tumultuous career had seen glory days and devastating disappointment, and 290 of the 483 games Roe would pitch in professional baseball were history.

Despite the forgettable majority of his career and the fact that he was now 32 years old, Roe would become one of baseball’s most respected pitchers with the Dodgers. Preacher Roe was now one of the Brooklyn “Boys of Summer,” made unforgettable by Roger Kahn’s acclaimed book.

When Roe arrived in Brooklyn, manager Burt Shotton, who had seen Roe years earlier as a minor leaguer, would hardly recognize his new pitcher. Shotton recalled a hard-throwing fastball pitcher, “as fast as hell, but wilder than any human I ever saw, but by 1947, he had become a pitcher.” Roe’s new pitching style featured three strides, seven pitches, and five speeds.

Occasionally, these various deliveries were supplemented by a Beech Nut gum-enhanced “sinker,” better known as a spitball. Perhaps more effective was Roe’s “fake spitter.” The painfully slow-working Roe would fidget, go to his cap, his belt, and his ear to make the batter think the spitball was coming, only to throw a fastball or slow curve.

Despite a new skillset, Roe started slowly in 1948. His record at mid-season stood at 3-4 when he finally mastered the intricacies of his new control-based style. He was 9-4 in the second half and the Dodgers’ best starter by season’s end.

In the 1949 pennant race that went down to the final game, the Dodgers edged the Cardinals by one game for the National League crown. Preacher Roe went 15-6 and led the team in ERA. Roe won Game Two of the World Series against the Yankees in what he later recalled was his greatest day in baseball. With his family from Arkansas in attendance, he shut out the powerful Yankees on six hits. It would be the only game the Dodgers would win in the series.

Roe won 19 games and once again led the team in ERA for the 1950 Dodgers, who finished two games behind the Phillies in the season of Philadelphia’s celebrated “Whiz Kids.”

Roe had his best season statistically in 1951. His won/loss record of 22-3 was the best winning percentage (.880) in the seventy-plus years the Dodgers played in Brooklyn. Although Roe’s memorable 1951 season was the benchmark of an outstanding career, it was a season Dodger fans would try unsuccessfully to forget for generations. Bobby Thompson’s historic homer in a one-game playoff secured the pennant for the cross-town Giants and climaxed a heartbreaking tumble for the Dodgers, who blew a thirteen-game lead in the last 50 games of the season.

The Dodgers won the pennant again in 1952 and, although Dodger manager Charlie Dressen reduced 36-year-old Roe’s innings pitched to about 100 fewer than the previous season, he posted a remarkable 11-2 record. In a seven-game World Series loss to the arch-rival Yankees, Roe won Game Three and pitched well in relief in two other appearances.

In 1953, Dressen again wisely limited Roe’s innings, and Preacher coaxed another outstanding season from a tired left arm. The 37-year-old veteran went 11-3, and the Dodgers won their third pennant in five years. As had become their unfortunate tradition, Brooklyn lost the World Series to the Yankees four games to two. Roe started game two and pitched well until an 8th inning home run by Mickey Mantle beat him 4-2.

Preacher Roe’s years with the Dodgers were seasons of success and national acclaim. When arm trouble limited Roe to 63 innings in 1954, the Dodgers reluctantly traded him to Baltimore that winter. Unwilling to play elsewhere, he retired rather than join the Orioles. With Brooklyn, Roe was a celebrated major league star on a high-profile team. He was chosen for the All-Star team four consecutive seasons, and in 1951, he was selected the National League Pitcher of the Year by the Sporting News.

Lost in the record of his success as a Dodger is the story of the almost 300 games he pitched in before arriving in Brooklyn and his determination to reinvent himself after a devastating injury threatened his career and his life.

Elwin Charles “Preacher” Roe was chosen for the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1967 and was among the first inductees selected for the Harding University Hall of Fame in 1989. He died in 2008 and is buried in his adopted home of West Plains, Missouri.

Preacher Roe arrived in the major leagues based on talent, but he succeeded based on guile and an unrelenting determination he brought from his Arkansas roots. The first and best major leaguer from the old AIC…

___________________

A Subscription sends these weekly posts to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________________

Allen McDill, Arkansas Tech - The Last of the AIC Major Leaguers

The last former AIC baseball standout the reach the major leagues was Allen McDill of Arkansas Tech. McDill was an All-AIC pitcher for the 1992 conference champion Wonder Boys. McDill was 5-2 with 71 strikeouts in 71 innings on one of the three AIC titles won in Dale Harpenau’s 11 years as Wonder Boys coach.

McDill was drafted in the 20th round of the MLB draft by the New York Mets and made his major league debut on May 15, 1997. He pitched in his last major league game on October 2, 2001. McDill pitched in 38 major league games without a decision. He remains the Arkansas Tech baseball player with the most major league appearances.

McDill was inducted into the Lake Hamilton School District Sports Hall of Fame on Feb. 15, 2019. He was a four-year letterman in baseball at Lake Hamilton High School and conference most valuable player as a senior.

_____________________

May 2025 Mystery Player

Another challenge for those of you who like a good mystery. This member of the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame was associated with the Travelers, Razorbacks, AIC, and SWC.

____________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link

Even without the hint - I recognize the mystery man as CLIFF SHAW. (He was inducted into the ASHOF in 1981 - I only met him one time, when Lee Rogers set up the visit to the home of Bill Dickey back in the early 1980s.)

I’m gonna take a WAG and guess the mystery person as Dave Jorn!!!