Backroads and Ballplayers #103

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Storybook Series in the GAC, The AIC, Lost Story of George Harper.

I usually write the outline for my weekly column at my local Starbucks. They charge $3.22 for a cup of coffee, but they are friendly, the coffee is good, and I like coffee shops.

In the days when Harry Carey and Jack Buck did the Cardinals’ games on the "CODNAL" Baseball network, my dad paid a nickel for the bottomless cup at Carl West's Drive-In. Mickey Mantle was in New York, the Dixie Blues were at the old ballpark on the east side of town, and I wore a heavy wool uniform with OZARK on the front.

Before TV brought major league baseball to the living rooms in my hometown, we listened to the Cardinals on the radio, played against neighboring towns on our local youth league teams, and watched the town team play on weekends.

I loved to play, and I still think baseball is best appreciated in person. I can’t help but feel a little sad that in Russellville, Arkansas, the closest thing we have to those old town team days has finished its regular season. It was nothing short of amazing.

A Weekend in the GAC

Traditionally, the NCAA Division II Great American Conference regular baseball season ends the last week in April. Entering the deciding week, the five teams from Arkansas all had some kind of mathematical chance to be regular-season champs. Arkansas Tech would need a sweep of perennial contender Harding University and some help from their “friends” to have a chance at the title.

After winning both ends of a Friday doubleheader, it all came down to the final game on Saturday afternoon for Tech to claim the GAC Championship. In small-town Arkansas, with the title on the line, Russellville became the 21st-century version of the “picnic and baseball” events that sustained our great-grandparents during some of Arkansas’ most difficult days.

As usual in Division II, admission was free, as were the hot dogs, snocones, and a midway of games for the kids. It was a perfect spring baseball day. It started with a picnic and ended with a dogpile.

Arkansas Tech 2025 GAC Baseball Champion.

____________________

The GAC and the AIC

There are 12 baseball teams in the Great America Conference. Six from Arkansas and six from Oklahoma. In the final GAC baseball standings, the Arkansas teams occupy the first six spots. Arkansas Tech won 23 conference games, Southern Arkansas won 22, and Harding and UA Monticello each had 21 conference wins. Arkadelphia neighbors, Ouachita and Henderson, had 20 wins. The six teams from Oklahoma finished seventh through twelfth.

The six Arkansas teams were once members of a historic old league called the Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference (AIC). At one time or another from the spring of 1928 until the spring of 1995, most of the four-year colleges were members of the AIC.

For more about the AIC:

Rex Nelson writes the history of the AIC in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Under the leadership of former AIC coach and athlete, Vance Strange, the AIC Recordbook is available at the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame Website.

A Subscription sends these weekly posts to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________________

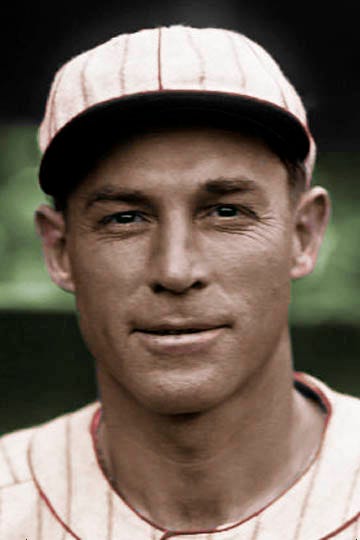

The Lost Story of George Harper

On March 19, 1953, Arkansas Governor Francis Cherry presented Arkansas Traveler certificates to two prominent Magnolia citizens as they left the state to begin a historic promotional journey. The two men would travel for six weeks from Atlanta, Georgia, to Magnolia, Arkansas, in a covered wagon pulled by Columbia County mules. The trip was designed to draw attention to Magnolia’s Centennial Celebration, scheduled to begin in May.

The men chosen to represent the city were O. D. Reynolds and George Harper. Better known around Columbia County as “Uncle Toad Frog,” Reynolds was an illustrious Magnolia character renowned for his ability to make effective extemporaneous speeches when called upon. This skill would come in handy on the trip. The other traveler, George Harper, was revered as one of Magnolia’s favorite sons. Now a semi-retired lumberman in his early 60s, Harper was very well known in south Arkansas, despite being 20 years separated from a stellar career in major league baseball.

George Washington Harper began working 12 hours a day as an adolescent to help his parents support a family of 12. The Harpers lived in Arlington, Kentucky, a few miles east of the Mississippi River. After school ended in 1910, he spent the summer with his sister in Fordyce, Arkansas, to earn a little spending money. The $1.50 a day her husband paid him to work in his barrel stave mill looked considerably better than his tough situation back in Kentucky. After that summer, George remained in Fordyce, and, at age 17, he became an Arkansan for life.

Harper was about a month short of his 21st birthday when he graduated from Fordyce High School in May of 1913. The summer after his graduation, he was playing semi-pro baseball for a team in Stamps, Arkansas, when a scout for Paris, Texas, in the Texas-Oklahoma League offered him a better deal than the stave mill. Harper reported to the Boosters in June and had a good first pro season, hitting .309. Later in the summer, he hit .297 in a 16-game promotion to Class AA Kansas City.

Fortified by his confidence as a professional baseball player, George Harper decided to make a daring personal move in the fall of 1913. In October, he rescued his girlfriend, Johnie Warmack, from her dorm room at Third District Agricultural School (later renamed Southern Arkansas University). The two impulsive young people made a hasty getaway to an elopement that did not sit well at the Third District school or with Johnie’s unhappy father. Despite the reckless beginning, George and Johnie were married for 48 years until her death in 1962.

After two successful seasons in the Texas League, he found himself in the major leagues with the Detroit Tigers in the spring of 1916. Desperate for players during the player shortage created by World War I, the Tigers tried him in 1916, 1917, and 1918. Nothing in those major league stints indicated George Harper was anything other than a fill-in for the major leaguers serving in the military.

At age 27, George Harper retired. He had played 160 major league games, batted .240, and failed to hit a single home run. Discouraged and disillusioned, Harper decided to give up professional baseball and return to a life that offered more stability. He headed back to south Arkansas after the 1918 season, bought a sawmill, and assumed the role of businessman with no intentions of ever trying major league baseball again.

The Little Rock Travelers convinced him to come to Little Rock for one game in August of 1919. Harper, away from baseball for about a year, was able to get a single in four trips. The local papers were hopeful, but the next day, Harper returned to his sawmill in Arkansas.

In May of 1920, Harper spent a few days with the Shreveport club, about an hour and a half from his home in Columbia County, but he came home to operate the mill before playing in any games. In July, he once again attempted to leave the mill operation to others and joined the Oklahoma City Indians in the Class A Western League. This time he stayed, finished the season, and hit a surprising .305. The following season, back in Oklahoma City, he had one of the best seasons in minor league baseball, with a .393 batting average and 19 home runs. The Cincinnati Reds purchased his contract from OKC in the winter of 1922 for $20,000. At age 30, after more than 700 minor league games and three unsuccessful stints with the Detroit Tigers, George Harper was an overnight success.

Although pneumonia kept him out of spring training, he was inserted into the Reds’ lineup early in the 1922 campaign and remained there all season. The George Harper playing in the Reds uniform in 1922 scarcely resembled the hobbled, timid, weak-hitting Detroit Tiger of 1918. He led the team in batting average at .340. He was third in RBIs, and, despite his inexperience, he struck out only 22 times in 482 plate appearances.

When future Hall-of-Famer Edd Roush returned from an extended holdout in 1923, the Reds’ outfield got crowded. Harper's playing time was greatly reduced. Playing sporadically, his success at the plate deteriorated significantly.

The Reds traded him to the Phillies 28 games into the 1924 season, and Harper flourished again, especially in the left-hander-friendly Baker Bowl. In three seasons in Philly, he hit .294, .349, and .314. No doubt aided by the short right-field wall in his home park, he became a consistent power hitter and RBI producer in Philadelphia, although the hapless Phils finished near the bottom of the standings each of the seasons.

In 1927, Harper was 35 years of age but still recognized as one of the league's most consistent hitters and a steady outfielder. Contending teams wanted a player like Harper in their lineup, and in 1927, that team was the New York Giants.

The Giants had been going backward in the standings in the mid-1920s despite a lineup filled with stars. In 1927, they added Harper, Rogers Hornsby, Edd Roush, and Burleigh Grimes to a roster that already had future Hall-of-Famers Travis Jackson, Bill Terry, Freddie Lindstrom, and Mel Ott. Grimes won 19 games, Hornsby hit .361, and Harper batted .331. The Giants finished third, and all three would find new team homes in 1928.

Twenty games into the 1928 season, the oft-traded Harper was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cards needed a quality player to complete an outfield that had Future Hall-of-Famer Chick Hafley and Little Rock native Taylor Douthit already in place. The 1928 Red Birds also had Frankie Frisch, Rabbit Maranville, Sunny Jim Bottomley, and a wily old pitcher named Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Harper hit .305 with 17 home runs the remainder of 1928, and, despite the late start, he was a key factor in the Cards’ pennant-winning season. He enjoyed the most success against his old team, the Giants. He not only hit .388 against his old mates, but he also had the ultimate revenge game against them during the Cardinals’ run to the pennant.

Although he was better off in St. Louis both personally and professionally, Harper's animosity toward his former team became publicly obvious on September 20 when he had an especially gratifying game at the Giants’ expense. Using a custom-made persimmon-wood bat he had designed at his Arkansas sawmill, Harper hit three home runs and drove in five runs in the first game of a doubleheader at New York’s Polo Grounds. After each homer, he made “gestures” specifically directed at Giants Manager John McGraw. The taunts aimed at the old Giants’ boss were described variously as playful and obscene, depending on the loyalty of the press. The three home runs in a single game tied the modern record at the time.

The 1928 Cardinals finished the season two games in front of the Giants to capture a pennant that was certainly sweet revenge for Harper. In the World Series, St. Louis ran into the Yankees at the pinnacle of their late-1920s greatness. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig combined for seven homers, and the Yanks won the series in four easy victories. In December, the Cardinals decided to move on from some of their team leaders and sold two 36-year-olds, George Harper and Rabbit Maranville, to the Boston Braves.

Harper led the 1929 Braves in home runs, and Maranville led in runs scored and stolen bases. The legendary Rabbit batted a respectable .284. Harper hit .291. The Braves finished last, and that fall, Harper was traded to Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League. His major league career was over at age 38.

George Harper’s occupation was baseball player, and he remained in professional baseball for six more seasons at various levels, including two seasons as player-manager at El Dorado. His last baseball assignment came in 1945 during World War II when he managed the Navy base team in Camden, Arkansas. In a fitting finale, on Harper’s 53rd birthday in June of 1945, he played an inning at each position for the Camden team. He donated $2,000 to the war bond effort on that historic day and topped it off with a home run.

After the war, Harper settled just outside Magnolia, Arkansas, and returned to his business interests. He volunteered at various baseball instructional schools, and, until his unusual covered wagon journey in 1953, his name was absent from “top of the page” news.

When the credentials of Arkansas’ professional baseball players are discussed and comparisons are debated, George Harper is often overlooked. Like Bill Dickey, whose Hall-of-Fame career was just beginning as his ended, George Harper was an adopted son rather than an Arkansan by birth. From his youth, he considered Arkansas his home.

Among Arkansans who played at least 1,000 major league games, Harper’s career batting average of .303 ranks fourth behind Arky Vaughan, Dickey, and George Kell. He was in the top 10 in home runs in the league for four seasons, and, for the years from 1922 to 1929, only six players in the National League hit more homers.

For his combined professional career in the major leagues and minor leagues, Harper had more than 2,500 hits and a career batting average well above .300. Using criteria unheard of in Harper’s day, his major league career OPS was .836. In comparison, Brooks Robinson’s OPS was .723, Kell’s was .781, and Travis Jackson’s was .770.

George Harper was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in January 1970. He died in Magnolia on August 18, 1978, at the age of 86.

___________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link

I attend a few games a year at a division 2 school not far from my house in Austin, TX (St. Edwards Hilltoppers) and it's a good time. ⚾

Fun write up.