Backroads and Ballplayers #101

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

New Mystery Photo, Up Next, “42,” and Jackie Robinson and Johnny Sain

April Mystery Photo - Do you know both individuals in this well-publicized moment? Hint on Thursday…

Down to two…

At the time of this writing, Major League Baseball has completed about 10% of its schedule. On Monday morning, April 14, there are only two Arkansas-born players in the big leagues. Both Jakob Junis (Jacksonville, Cleveland) and Jalen Beeks (Prairie Grove, Razorbacks, Arizona) are off to excellent starts as middle relievers. Junis has yet to allow a run in 8 innings, and Beeks has pitched ten-plus innings and allowed only one run. He was the winning pitcher in the Diamondbacks’ win over the Brewers on Sunday.

Who is next up? While Jordan Wicks and Jaden Hill are good bets, I have a new name for the next-Arky list. How about Connor Noland (Greenwood, Razorbacks, Cubs organization)? I am pulling for him. He gave up football at Arkansas to concentrate on pitching. He pitched through the COVID days, and he stayed four years in the Hogs’ baseball program. How many four-year lettermen are there these days?

I would like to say I thought he was a big-league prospect when he was the Razorbacks’ go-to guy as a senior, but honestly, I am somewhat surprised that he seems on the cusp of getting that life-changing phone call.

Noland was drafted by the Chicago Cubs in the 9th round (263rd overall) of the 2022 MLB June Amateur Draft. In his first minor league season, he won one of nine decisions, with a 4.08 Earned Run Average (ERA) over 24 games at Class A South Bend. The Cubs saw something beyond the stats.

Promoted to the Double-A level with the Tennessee Smokies in 2024, his performance showed significant improvement. Noland posted a 7-3 record with a 2.50 ERA in 16 starts over 86.1 innings pitched. He finished the year at the Cubs’ AAA affiliate in Iowa, where he raised his average strike-out rate to 9.25 Ks in nine innings.

Back with the Iowa Cubs to begin 2025, Noland is off to an excellent start. Although not a hard thrower, he is starting to make a name for himself in the Cubs system. After allowing one run in six innings Saturday, Noland has lowered his ERA to 1.69. Keep your phone with you, Connor.

While not an Arkansas-born guy, Kevin Kopps is off to a good start (2.61 ERA with 11 Ks in 10 innings). He is getting to the point in his career when he needs a breakthrough season.

____________________

A Subscription sends these weekly posts to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________________

Johnny Sain and “42”

Tuesday, MLB commemorates Jackie Robinson Day. Each year on this date, Major League Baseball honors Robinson’s historic debut on April 15, 1947. All players, managers, coaches, and umpires wear No. 42 in honor of his legacy and his contributions to American culture.

I cannot imagine the pressure Robinson must have felt as he played in a game that had historic significance far beyond baseball. Pulitzer-winning baseball writer, Arthur Daly, offered his take in the New York Times:

“Robinson almost has to be another DiMaggio in making good from the opening whistle.” Daley wrote. “It’s not fair to him, but no one can do anything about it but himself. Pioneers never had it easy, and Robinson, perforce, is a pioneer. His spectacular season in the International League is no guarantee that he’ll click just as sensationally in the Big Time. Too many minor-league phenoms have failed for this to be a guideline. It’s his burden to carry from now on, and he must carry it alone.”

I have intentionally watched the movie “42” at least five times and accidentally watched various parts of it several more times. I love Harrison Ford as Branch Rickey and Lucas Black as Pee Wee Reese. The late Chadwick Boseman is an excellent Jackie Robinson, and he carries the baseball scenes very well. Casting in baseball movies is important, and miscasting can be fatal to the movie’s success (William Bendix, John Goodman as Babe Ruth).

Historical fiction is tricky. A sizable percentage of the intended audience knows the basics of the true story. They want the movie to be accurate. A larger part of those who see the movie know very little about the story on which the film is based. They expect to be entertained. Since movies are made to be entertaining, the writers sometimes feel obligated to “enhance” the true story.

I can imagine the pre-production planning for “42.” The producers and director have a meeting with the baseball consultants: “Folks, we need a group of antagonists. That should be easy, we hear Robinson had a tough time with players who opposed the integration of big league baseball.”

Intent on accuracy, the baseball historians suggest Fred Walker from Georgia. His nickname was “Dixie,” and he was vehemently opposed to Robinson joining the Dodgers. Walker would later defend passing an anti-Robinson petition among his teammates as necessary to protect his business in Alabama.

Philadelphia had a reputation as a tough place to play, so the writers suggested Ben Chapman, who was manager of the Phillies when Robinson debuted with the Dodgers. Chapman was from Nashville, Tennessee, and so opposed Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier that he instructed his players to harass and taunt Robinson with insults and racial slurs. Baseball history supports the decision that Chapman had earned the villain role.

The producer may have suggested, “What about the guy who threw the first pitch to Robinson. He was from Arkansas for Pete’s sake; he must have been an outspoken segregationist!”

The historians had nothing. Johnny Sain wasn’t much of a talker, and any quotes about pitching against Jackie Robinson were about baseball.

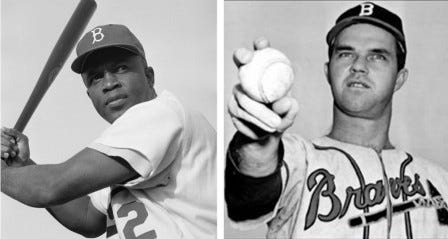

Beyond race, John Franklin Sain and Jack Roosevelt Robinson could hardly have been more different. Robinson, a compact, muscular young man, was a natural athlete. He was a product of the West Coast and a multi-sport star at UCLA. He was specifically chosen from what was then called the “Negro Leagues” by Brooklyn Dodgers’ owner Branch Rickey. College-educated, thoughtful, but passionately competitive, Rickey was convinced Robinson could win the support of his teammates and handle the pressures of blatant discrimination.

Johnny Sain’s father taught him how to throw a wicked curveball and was convinced young Johnny had the talent to be a big-league pitcher. Others were much less certain. Sain was 6’2’ and weighed about 200 lbs. He looked like he could throw hard, but his fastball was average at best. Sain was laughed at, discouraged, and told to go into the necktie business, but father and son would not give up.

After high school, Sain spent four years in the Class D Northeast Arkansas League and two years with Class “A” Nashville. In 1942, Boston Braves’ manager Casey Stengel signed him to replace regulars lost to the military due to World War II. Sain won four and lost seven with the Braves before getting his draft notice later in the year.

Remarkably, Johnny Sain improved as a pitcher more in the military than at any time in his professional career. Sain returned to the Boston Braves in 1946 as one of the league’s best pitchers. Later, Sain would credit the confidence and maturity he gained in military service as the major reason for his amazing improvement. After winning only four games previously in the majors, Sain won 20 in 1946.

Despite vastly dissimilar backgrounds and different paths to the major leagues, Johnny Sain and Jackie Robinson would share the stage on Opening Day, 1947. In retrospect, it may have been the most seminal pitcher/hitter confrontation in baseball history.

April 15, 1947, arrived chilly and gray in Brooklyn, and the unspoken questions surrounding the first African-American major leaguer were about to be answered. Secret petitions had been squelched, boycotts avoided, and players had been warned. Now it was simply time to play the game. What kind of reception would Robinson receive from the fans and, more importantly, from opposing players? How would Southerner Johnny Sain handle his crucial role in American history that was about to unfold?

Looking back, Sain recalled he had little interest in anything except pitching. “It wasn’t that big of a deal at the time,” Sain said. “People ask me if I was worried about letting a pitch get away and hitting him, and I say no. I wasn’t even thinking about that kind of stuff.”

Johnny Sain threw the rookie a steady diet of his signature curveballs. Sain’s sweeping, knee-buckling, breaking ball was vastly different from anything Robinson had seen in the minors. Although the Dodgers prevailed 5–3, Robinson failed to get a hit. When asked after the game if nervousness had contributed to his lack of hitting, Robinson replied, “The reason I didn’t hit well was Johnny Sain’s curveball.”

The first baseball game with an African-American player had occurred without incident. Jackie Robinson was treated with respect by the Braves and cheered by fans on his first big league day. Unfortunately, this would not always be the case. Robinson faced unspeakable torment and racial taunting by opponents and fans throughout his rookie season. As Branch Rickey had requested before the season began, Robinson ignored the insults and focused only on baseball.

While Babe Ruth and the home run he popularized changed baseball, Robinson’s grace and courage contributed to a more universal cause, a crusade for equality that continues to this day. Johnny Sain’s part of the Jackie Robinson story is a positive episode in his legacy. Unlike many players of his day, he did not provide quotes laced with racially motivated resentment, which he would someday regret.

Unfortunately, great players who played on opposing teams and a handful of his teammates would have the story of their baseball careers tainted by their intolerance of Jackie Robinson. Arkansas’ Johnny Sain’s part in the Jackie Robinson story is limited to curveballs, double plays, and an opening day loss for his Braves.

Sain enjoyed three World Series Championships in the early 50s, with the Yankees. He was chosen for the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1966 and the Braves Hall of Fame in 2002. Johnny Sain died in 2006. He is buried in Havana Cemetery in Yell County, Arkansas.

____________________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link