Backroads and Ballplayers #100!

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

Two years ago this week, Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly was published for the first time. Backroads and Ballplayers is dedicated to saving the lost stories of Arkansas baseball history. BRBP Weekly will always be free.

THANK YOU!

April 8, 2023: BRBP #1 - 25 Subscribers

April 7, 2025: 100 Years Ago: A Bellyache that killed Babe Ruth, rise and fall of the Yankees, end of Aaron Ward’s glory days.

and

RAINY DAYS AND BASEBALL SONGS …300+ Subscribers

The Bellyache Heard ‘Round the World

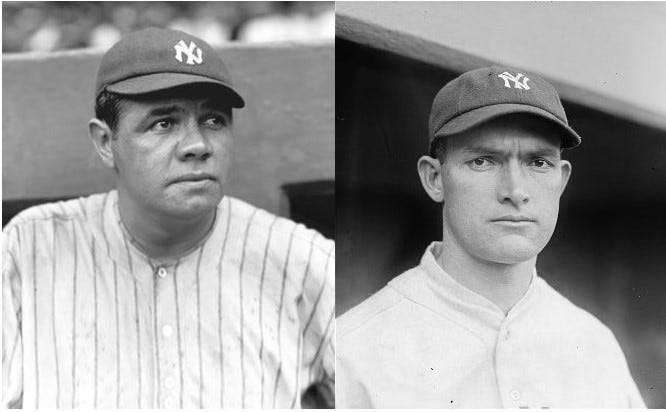

A couple of weeks ago, Philip Martin wrote in the Arkansas Democrat Gazette about Babe Ruth’s untimely death in 1925. The tragic news that the Great Bambino was deceased made headlines around the world, but the most “untimely” thing about the news was that The Babe wasn’t dead. He may have wished he was!

Babe loved Hot Springs, where he had been going for several years before 1925. Ruth and his buds went there to “train.” He loved the hills where he claimed to walk off the excess poundage he had gained in the temptation-filled world up north. Really?

Yes, he did love the Spa City. He may have taken a walk or two and played a few practice games in those wool sweaters the players wore in those days, but there were other attractions in Hot Springs. He may have liked the golf, gambling, bar life, and the ladies more than the “spring training.”

Already out of shape and nursing a digestive problem, Hot Springs was the last place Babe Ruth needed to be in the spring of 1925. The regime of “spring training” in Hot Springs would be declared off-limits after 1925.

I don’t know if you can access Martin’s column about the Babe, but you should try. He is simply the best baseball writer in Arkansas. Yes, there are some…

The Bellyache Heard Around the World - Phillip Martin

____________

A Subscription sends these weekly posts to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

____________

The Decline of Aaron Ward

Aaron Ward, the hero of Logan County, Arkansas, was promoted to the Yankees with modest expectations. He had done little to predict that he could hit major league pitching. Realistically, he had not experienced much success hitting minor league pitching. One reporter from a Little Rock newspaper remembered him as a good infielder who “Couldn’t hit a lick.”

With players in short supply due to World War I, the Yankees gave Ward a shot in August of 1917. He batted .115 in eight games. In 1918, his second season in New York, Ward remained on the big-league roster all season. He played in 20 games as an emergency fill-in and raised his batting average to .125.

Although more quality players were becomming available, Ward played the same role in 1919. He appeared in 27 games. Ward batted .206 and raised his career RBI total to three. He had proven the sportswriter’s assessment. Aaron Ward couldn’t hit a lick…and then he could!

With no hint of success in big-league baseball, Aaron Ward was about to become an integral part of the story of the Bronx Bombers.

The day after Christmas 1919 became the most memorable non-game day in the history of the New York Yankees franchise. On that day, the Yankees purchased the services of George Herman Ruth from the Boston Red Sox for $100,000. The extraordinary bargain would lead to legendary success for the Yankees and a run of bad luck in Boston so inexplicable that Red Sox fans declared it to be a curse.

For Aaron Ward, February 12, 1920, would be the day his career took a fortunate turn as a result of a tragic event. On that date, venerable Yankees third baseman Frank “Home Run” Baker’s 31-year-old wife died of pneumonia at her home in Pennsylvania. The loss left two small children in Baker’s care and ultimately became a crisis for the New York Yankees. The future Hall of Famer announced a few days later that he would not return to the Yankees but would devote his time to the care of his daughters.

Baker stayed true to his word, and after a few weeks of experimenting with various combinations, the 1920 Yankees settled on a new right fielder by choice and a new third baseman by elimination. The somewhat desperate Yankees tested several candidates at third in early April, eventually giving Ward the job amid obvious skepticism. He would soon turn that doubt into cautious optimism.

In the first three months of the 1920 season, Ward met only the Yankees’ modest expectations. He produced mostly singles at the plate, and, despite his history as a middle infielder, Ward handled the unfamiliar hot corner well enough. The Yanks anticipated a temporary caretaker for Home Run Baker’s position, and a light-hitting glove-man would have to do.

Fortunately for Aaron Ward, by mid-season, he seemed to adopt a more aggressive hitting strategy that he may have learned by observing his new teammate Babe Ruth. In the last half of the season, Ward more than doubled his extra-base hits, including nine home runs.

Babe Ruth hit an incredible 54 home runs, more than the total for the combined roster of any team in the American League. Ward’s 11 homers for the season would tie for second on the Yankees and seventh in the American League.

Home Run Baker returned in 1921, and, while Baker reclaimed his old position at third, the Yankees traded well-respected second baseman Del Pratt to Boston. The deal would bring future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Waite Hoyt to New York and open second base for Aaron Ward.

Beginning in 1921, Ward no longer needed to look at the card posted in the dugout to see if he was in the lineup. He led the team in games played and raised his batting average to an improbable .306. More in line with expectations, his defense was outstanding. Ward was third among the league’s second sackers in assists and third in fielding percentage.

Ward's hitting fell off in 1922, but he continued to lead the team in games played. His .267 batting average was more than acceptable, considering he was one of the league's premier defensive infielders. He led all American League second basemen in assists and was second in fielding percentage.

The rebuilding Yankees moved to the top of the standings in Ward and Ruth’s second year in the lineup, winning the American League pennant in both 1921 and 1922. The Yanks success initiated a contemptuous rivalry with the team that owned their home field.

The New York Giants won both the 1921 and 1922 World Series in their first postseason matchups with their tenants, but the Giants were tired of sharing the Polo Grounds with the more popular Yankees. The Giants gave their rivals until 1923 to find a new place to play home games.

The Yankees did more than find a new home field. They built the most recognized baseball stadium in America. The “House that Ruth built” would be known as Yankee Stadium and become the most iconic venue in baseball history.

The 1923 season opened in the Yankees’ new edifice on April 18, with an announced attendance of 74,000 and another 25,000 left outside. In the home half of the third inning, the fans got what they came for. A 26-year-old second baseman from Booneville, Arkansas, hit a sharp single between short and third for the first hit by a Yankee in the new stadium. Later in the inning, right on script, Ruth hit the first home run in the new park. Ward got a box of cigars for his inaugural hit, and the Yankees started the season with a 4–1 victory in what would become the year the Yanks began the ascension to legendary status.

That Opening Day launched the season the Yankees had been building toward since they acquired Babe Ruth and started assembling a competitive team around him. New York coasted to the American League pennant by 16 games, and Aaron Ward was now a complete player. Hitting in the middle of the Yankees lineup, Ward hit a solid .284, drove in 81 runs, and was second on the team to Ruth in homers and triples. He led the league’s second basemen in fielding percentage and assists. Manager Miller Huggins proclaimed, "He is a real ballplayer, one of the best in either league."

The Yankees capped the year by defeating their arch-rivals, the Giants, four games to two in the 1923 World Series. It was the third consecutive year the bitter rivals had met in the fall classic and the first championship for the Yanks.

Aaron Ward led World Series hitters with 10 hits and a .417 batting average. He handled 38 chances in the field without an error, including the last out—a weak ground ball to second base.

Back in Booneville, Ward’s friends and family followed the exploits of their famous favorite son. The Arkansas Gazette reported, every move of the World Series was received by scores of anxious fans in Booneville over the radio. “Every time our ‘Wardy’ made a hit or scored a run, the folks over in the next county knew it by the cheers.”

Aaron Ward was a World Series Champion, playing on the country’s most popular team, and sharing a national spotlight with the “Great Bambino.” He was 26 years old, but his best years were behind him.

The year after the Yankees’ series triumph, the knee problems that had haunted Ward’s career since his football days at Ouachita returned. The Yankees faded to second place in 1924 and seventh after the infamous bellyache of 1925. They would recover to build another Ruth-led Bronx Bombers team in the last half of the decade, but they would create their new “Murderers Row” image without Aaron Ward.

After he played in only 22 games in 1926, the Yankees traded their injury-prone second baseman to the Chicago White Sox. Ward finished his big-league career two years later with a brief stint in Cleveland.

Aaron Ward played a few more minor league seasons, and by the early 1930s, he was playing for a semi-pro team in West Texas. He moved to New Orleans after his retirement, opened a tire store with his son, and became one of the city’s prominent amateur golfers. Aaron Ward died in 1961.

Baseball Songs

After what seems like a week of constant rain, I have some baseball music for you. Do yourself a favor and listen to some of my favorite baseball songs, and tell me that at least one of them doesn't make you smile.

Right Field - Always my personal favorite…

____________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome, new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link