Backroad and Ballplayers #96

Stories of the famous and not-so-famous men and women from a time when baseball was "Arkansas' Game." Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly is always free and short enough to finish in one cup of coffee.

When Arkansas Country Boys Ruled! Mystery Photos…

I devoted all the space in last week’s post to the multifarious details in the Gene Bearden story. The saga of the lefty from the Arkansas Delta highlighted the sports pages in the late 1940s. Gene Bearden was a World Series hero, co-starred in movies with Jimmy Stewart and June Allyson, and told a courageous war story that proved to be contrived. If you missed last week’s post, you can find it at this link.

“A Story About a Story”-Backroads and Ballplayers #95

The Post-War Years and Pitchers From the Arkansas Backroads

Gene Bearden won 20 games in 1948. From 1945 through 1951 four other Arkansas country boys would also have 20-win seasons. Of course, you can name those guys, right? Give it a try.

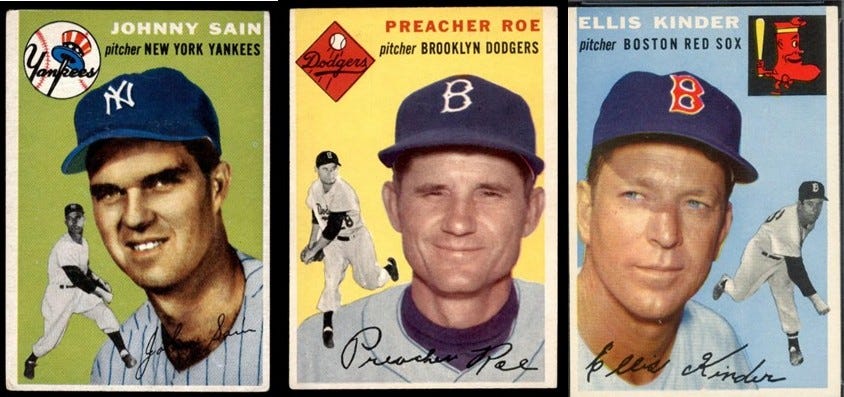

Yes, that is three…

Johnny Sain did it four times. In various seasons during his 11-year career, he led the league in games started and games finished. Sain led the National League in pitching victories in 1948, and although it was not an official statistic at the time, he led the American League in saves in 1954.

Ellis Kinder won 23 for the Red Sox in 1949. The colorful Pope County native with a knack for celebrating was the only pitcher from the decades between 1940 and 1960 to post 100 pitching wins and 100 saves.

Preacher Roe won 22 for the Dodgers in 1951. His 22—3 record led both leagues in winning percentage. And…Gene Bearden won 20 games in the 1948 season and added a dramatic story that made him a national celebrity.

So, Sain won 20 or more four times, Kinder won 23 in 1949, Preacher won 22 in 1951, and Bearden won 20 in 1948. That is the four you might have known. Can you name the fifth Arkansas-born pitcher who won 20 games in 1945? He actually won 22.

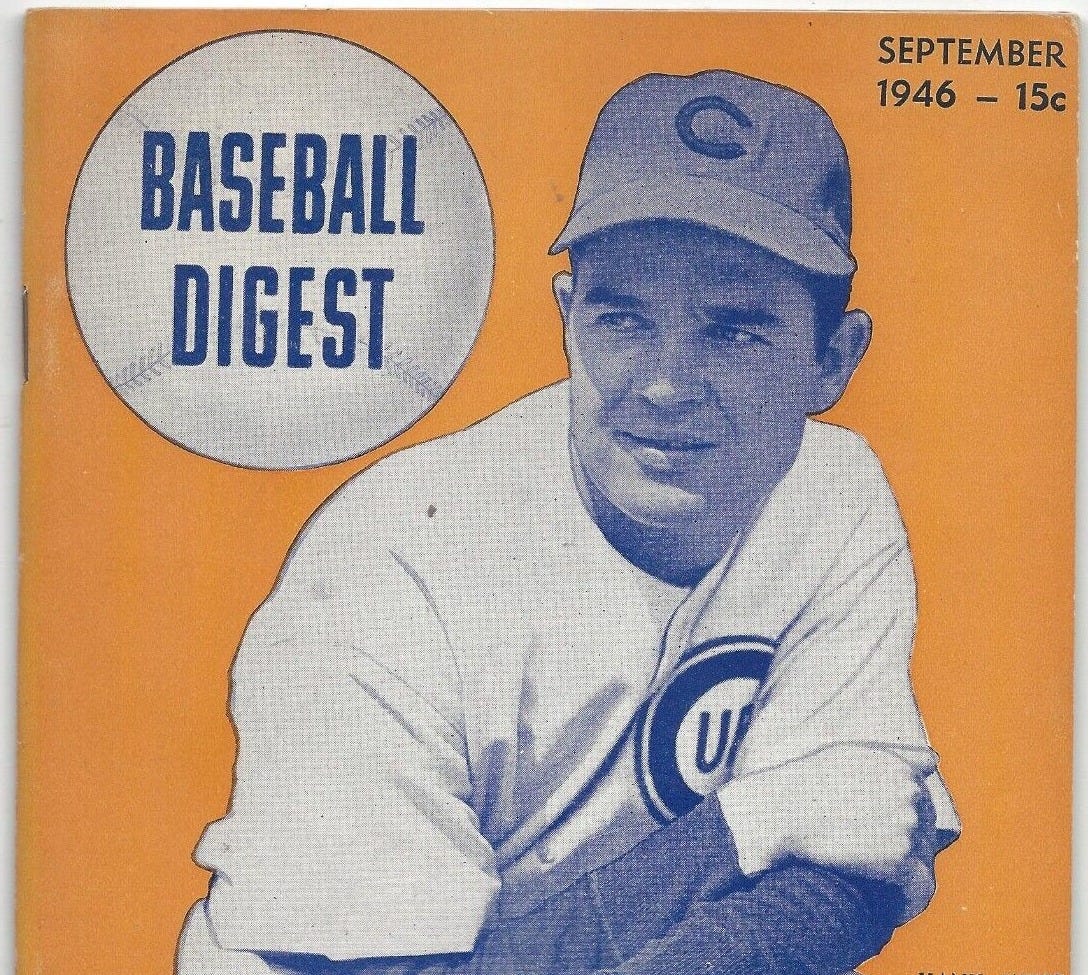

Okay, a photo hint that may give it away. He made the cover of Baseball Digest. He was born in Lunsford, Arkansas, and grew up in McCormick. Got it?

He pitched in the World Series, an odd thing to happen to a Cub during those days.

All this mystery to get around to a lost story about a guy from Poinsett County, named George Washington Wyse. Being a 22-game-winner for a Cubs team that played in the 1945 World Series, and finishing seventh in the MVP voting should save a guy from having a lost story. Those accomplishments have not saved Hank Wyse from obscurity. Starting today we are saving his story.

Twenty victories in a single season is considered a benchmark for success as a pitcher. Moving that arbitrary mark to 22 wins suggests an even more selective accomplishment and creates an unofficial elite fraternity of Arkansas’ distinguished major league greats.

The list of Arkansas-born major league pitchers who reached 22 or more pitching wins in a season reads like an honor roll of celebrated stars. The “22-win club” includes Dizzy Dean, who accomplished the feat three times, Lon Warneke, who won exactly 22 on two occasions, and Cliff Lee, who won 22 in his Cy Young Award year of 2008. The other well-known names in the prestigious group are Ellis Kinder, Johnny Sain, Preacher Roe, and of course Hank Wyse.

All the prominent pitchers on our list are members of the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame, except Wyse. The list includes Cy Young Award recipients, World Series heroes, Baseball Hall of Fame members, and the considerably less renowned, Hank Wyse.

Henry Washington Wyse was born in Lunsford, Arkansas, in 1918, or perhaps a few years earlier, if the 1920 census is accurate. The census indicates Henry was 4 and 11/12 years old in 1920. It would be common among pro baseball players in Wyse’s era to “lose” a few years to be more attractive prospects.

Regardless of his age, Wyse was raised in hard times. Assuming his accepted birth date, Wyse lost his father at age 12 and dropped out of school in eighth grade to help his family get by during the depression. By his mid-teens, he was working full-time for a lumber company in Trumann and playing semi-pro baseball for the company team on weekends.

In the late 1930s, Wyse’s career got a major boost when his mother moved her family to Kansas City to find work. In the city, Wyse’s pitching prowess got the attention of pro scouts, and he became a highly regarded prospect, pitching in the Ban Johnson League. The Chicago Cubs signed Wyse in 1940 and sent him to the Moline, Illinois, Plow Boys in the III League. Playing for a team called the Plow Boys was an appropriate start for a young man with Wyse’s background.

In July, with a 9—7 record but an unimpressive 5.55 ERA, the Cubs had seen enough to promote Wyse to their Class A farm team in Tulsa. In Tulsa, Wyse was assigned an Arkansas-born roommate named Dizzy Dean. Diz had spent most of the season with the Oilers trying to get his mojo back. Wyse finished his 32-inning Tulsa stint with a 2—2 won/loss record and a 3.08 ERA. When asked what insight he had gotten from Dizzy Dean, Wyse replied, “He showed me how to read the Racing Form.”

Back in Tulsa for the 1941 campaign, Wyse had an attention-getting season. He won twenty, lost only four, and posted a team-leading 2.09 ERA. Wyse’s performance led the Oilers to the finals of the Texas League playoffs, where he was outstanding in a losing effort.

In 1942, Wyse was again impressive for the Oilers. He and fellow Arkansan, Jittery Joe Berry, pitched in 88 games and combined for 38 pitching victories. Wyse’s 20 wins led the team, despite an early September promotion to the Cubs. He was 2—1, in 28 major-league innings with the Cubs, including a complete-game shutout of the Phillies on September 17th.

Wyse missed most of spring training in 1943 to care for his seriously ill wife, but the Cubs saved a spot on their roster for his return. Wyse had earned his permanent major league promotion, and despite a late start, he became an integral part of the Cubs pitching staff. Wyse started 15 games and relieved in 23. He picked up nine wins and five saves.

Wyse returned to the Tulsa area in the winter of 1943. Hank Wyse and his young wife had made their off-season home in Oklahoma since his days with the Oilers. Hank worked in a defense plant and continued to deal with his wife’s declining health. Rowena Patrick Wyse died on November 21, 1943. She was 24 years old.

On the first day of the 1944 season, Wyse tossed a five-hit shutout to beat the Reds 3—0. The opening-day win was a deceptive precursor to a miserable start for the Cubs. After Wyse’s inaugural win, the Cubs lost 13 straight and 16 of their first 18. A managerial change to a veteran baseball man named Charlie Grimm turned things around.

The 1944 Cubs eventually climbed to 4th place, their first appearance in the first division of the National League since 1939. Wyse led the team in wins, games started, and innings pitched. The master of a knee-buckling curveball, Wyse was tagged with the nickname “Hooks” by his teammates. In a harbinger of things to come, the 1944 Cubs went 24—16 in their last 40 games.

Cubs fans were accustomed to disappointment, but the 1945 season would be magically different. As the season began, some regular players were being discharged and returning to their major league teams, but rosters were by no means at pre-war levels. Overall talent was still more equivalent to the high minors than the big-league level. The Cubs were better off than many clubs, with a starting eight similar to the two previous seasons.

In mid-June, the Cubs were in the middle of the standings, and Wyse was a respectable 7—5 when bad news arrived. No longer the caretaker of an invalid wife, Wyse was summoned by his draft board in Oklahoma to report for induction on June 24th.

Although Wyse had previously passed a military physical in 1944, he had suffered a work-related injury to this back in the winter of 1945, and he now wore a medical corset when he pitched. The new injury was debilitating enough for Wyse to be rejected for military service before induction.

On July 1, the Cubs were in 4th place, five games behind the Dodgers, when Wyse joined the team in New York. After a 36-hour train ride from Oklahoma, Wyse pitched the second game of a doubleheader and beat the Giants 4 - 3. That remarkable win, by a pitcher who had been idle for ten days, began one of the most remarkable months in Cubs history.

The Cubs’ win on Wyse’s first day back in uniform, began an 11-game winning streak and a 26—6 record for July. Wyse was the winning pitcher in eight of those victories. In one month, the Cubs went from 4th place to league leaders, five games ahead of the Cardinals and Dodgers. Wyse’s return was the catalyst for the Cubs’ historic ascent.

A Sporting News feature from late July, chronicling the Cubs’ meteoric rise to first place, indicated that at least some baseball moguls understood the significance of Wyse’s return. The paper reported an incident from early July involving Dodger boss Branch Rickey. According to feature writer Edgar Munzel, Rickey was in his office, cheerfully watching the crowd file into Ebbets Field to see the first-place Dodgers, when a secretary broke his mood with a report that Wyse had failed his military physical back in Oklahoma. The suddenly pensive Rickey reportedly replied, “That’s too bad...too bad.”

It was indeed too bad for the Cubs’ National League competitors. The Cubs didn’t maintain their torrid mid-summer pace, but they held off the Cardinals and Dodgers the rest of the way and finished in first place by a game and a half over the second-place Cards. Hank Wyse won 22 games, second in the National League. He was also second in the league in innings pitched and third in winning percentage. Wyse was named to the Associated Press National League All-Star team, although the official All-Star Game was canceled because of the war-time travel restrictions.

Another highlight for Wyse during that historic July of 1945 occurred on July 12. In a 6—1 complete-game victory over Boston, Wyse held the Braves’ Tommy Holmes hitless, ending Holmes' hitting streak at 37 games. Holmes’ mark remained a National League record until broken by Pete Rose in 1978.

The 1945 World Series was a hotly-contested seven-game affair that featured classic pitching duels in games one through four. Wyse lost game two 4—1, although he pitched well, exempting a disastrous 5th inning when he gave up all four runs. Three of the runs scored on a Hank Greenberg homer. Greenberg had returned to the Tigers in mid-season from three years of military service. The Future Hall of Famer hit two home runs and three doubles in the series. He knocked in seven runs. Greenberg’s early return from the military likely doomed the Cubs.

Wyse appeared in relief in game six but gave up three runs in less than an inning’s work, an inauspicious performance that likely cost him a start in game seven. With the series tied at three, Grimm went with Hank Borowy in game seven, although he had pitched four tough innings in game six. Borowy had been added in a deal with the Yankees in late July, and his 11—2 record for the remainder of the year led the Cubs for the last half of the season.

After pitching the previous day, Borowy failed to get anyone out in the first inning and gave up three runs. Another starting pitcher, Paul Derringer, followed Borowy and gave up three more. Down 6—1 after two innings, the Cubs went on to lose the deciding game 9—3. Wyse mopped up by pitching a scoreless ninth.

Wyse did little in the series to instill confidence in Manager Charlie Grimm, but in hindsight, he was openly critical of the decision to start the overworked Borowy in game seven. In an interview in 1998, an 80-year-old Wyse blamed the manager’s decision for the Cubs’ series defeat. “It was Grimm’s fault,” Wyse stated bluntly. “It was a mistake. I thought so then and I still do.”

Although they had become reluctantly accustomed to losing, the 1945 World Series was a tough loss for the Cubs and their fans. With regular players returning from the war, there was a sense that an aging club that had benefited from diluted competition could not duplicate their 1945 success. That assumption was indeed correct. The Cubs would not play in another World Series for 71 years.

Wyse remained with the Cubs for two seasons after the “regulars” returned from military service. He was the ace of the Cubs’ staff in 1946, and his 14 wins led the team. His excellent 2.68 ERA, against the full rosters replenished after the war, was 7th best in the league and matched his mark for the previous year. The Cubs finished third, a distant 14 ½ games back. In 1947, Wyse dropped off to 6— 9 with an ERA of 4.31. He was demoted to a long reliever by mid-season and the Cubs faded to sixth place.

Bone spurs in his elbow sidelined Wyse in the spring of 1948. A sore-armed Wyse started the season with the Cubs and hung around the big club until May 30, without pitching an inning. On that date, national sports pages announced that he had been optioned to Shreveport in the Texas League. Wyse recovered well enough to post a 12-8 record and a 3.42 ERA in 32 games in Shreveport.

Hank Wyse opened the 1949 season with Los Angeles, the Cubs’ farm team in in Pacific Coast League. He lasted 5 games and 27 innings before being waived and landing back in Shreveport. As had been his history, Wyse thrived back in the Texas League, winning 18 games and leading Shreveport in virtually every significant pitching category. Wyse was back in top form and back in the headlines. Unfortunately, all the headlines were not related to his pitching comeback.

As Shreveport prepared for the playoffs at the end of the regular season, Wyse made the news by being arrested in Houston for drunk driving and driving without a license. He compounded his bad press by being involved in a jailhouse brawl with fellow inmates during his arrest. Shreveport was left with little choice but to suspend Wyse for the playoffs.

Despite his off-the-field transgressions, Wyse had regained enough of his old form to get a major league offer, albeit with the major leagues’ worst team, the Philadelphia Athletics. Philadelphia manager, Connie Mack, was now 87 years old and in his last year. He offered Wyse the standard $5,000 per year contract for a drafted minor leaguer, but Wyse declined. After proving himself in the spring, Wyse convinced Mack to increase his offer to a more palatable $8,000.

Wyse won 9 games on a weak pitching staff for the last place A’s in 1950, but at age 33, or perhaps several years older, Hooks’ dominating curve was no longer big league quality. Washington purchased his contract from Philadelphia in May of 1951, and the Senators subsequently sold him to the Yankees a month later. Farmed out to the Yankees’ minor league club in Kansas City for the remainder of 1951, Wyse was finished as a major league pitcher.

Determined to continue pitching, Wyse pitched two more somewhat successful minor league seasons before retiring in 1953. He finished his career with very respectable major league totals that included 79 wins and a 3.52 career ERA. His minor league record of 115 - 69 and a 3.15 ERA are even more impressive. Wyse’s 194 professional wins rank 10th among native Arkansans.

Wyse spent his baseball retirement working as an electrician in Oklahoma. He was elected to the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame in 1967 and the Texas League Hall of Fame in 2009. He died in Pryor, Oklahoma, in 2000.

At his best, Wyse was a major league star, although some of his accomplishments are marginalized because his best years came during World War II. "I guess I'm considered a wartime player, but I think I did pretty well in '46 when all the guys were back." At the time of his death, Wyse was the last Chicago Cub to throw a pitch in the World Series.

Last month’s Mystery Photo: Robert Henry Mavis

Bob Mavis starred for five years with the Arkansas Travelers. Five years is a long time to play full seasons with one minor league club. He not only played with the Travs those years, he was outstanding. Mavis batted over .300 each year, and he led the team in various offensive categories many of those seasons. Mavis loved Little Rock, Arkansas, and Arkansas loved him.

By 1949, after five excellent years in Arkansas, Mavis and the Travelers had become the property of the Detroit Tigers, and he was finally promoted to the Tigers AAA club in Toledo. He hit .300 again at the higher level and managed to hit 12 homers, a respectable number for a 5’7,” 150 lb. infielder. Mavis had earned his chance in the majors and when the Toledo Mud Hens’ season ended, he got the call to report to the Tigers.

Mavis traveled with the Tigers throughout September but did not get into a game until September 17th, when he made his major league debut, on a Saturday, in historic Yankee Stadium. More than 40,000 fans inadvertently turned out for Mavis’ first game. In a situation not unlike Franklin County’s Scat Davis three years earlier, Bob Mavis entered the game as a pinch runner with his team behind. Unlike Davis’ debut, however, Mavis’ appearance did not have a happy ending for his team. Mavis pinch ran in the top of the 9th for backup catcher Bob Swift, who had reached base on Phil Rizzuto’s error. A fly ball and a walk later, Mavis was on second, with a runner on first and one out, when Johnny Lipon grounded into a game-ending double play. That pinch-running appearance was Bob Mavis’ one and only big league game.

Mavis would play six more years of minor league baseball and later get a brief chance to manage his beloved Arkansas Travelers. He retired as an active player in 1957 but continued to scout throughout the South for several major league teams. Bob Mavis had chosen to call Little Rock home during his playing days and remained there while working as a scout.

Mavis died in Little Rock in 2005, as one of the all-time Arkansas Traveler greats and a former major leaguer.

Correctly identified by Caleb Hardwick

March Mystery Photo (Courtesy Ronnie Clay Collection) Can you identify this well-known baseball guy?

____________________

A Subscription sends the weekly post to your mailbox. There is no charge for the subscription or the Backroads and Ballplayers Weekly.

If you do not wish to subscribe, you will find the weekly posts on Monday evenings at Backroads and Ballplayers on Facebook. SAVE THE LINK…

__________

More Arkansas baseball history and book ordering information: Link

Welcome new subscribers. Have you missed some posts? Link

Re Wyse -- I feel certain that 1946 was the first year that the AP announced a post-season Major League All-Star team. Very interested that you mention that Wyse was named to an AP post-season major league All-Star team for 1945.

I have never seen this photo -- but, at first glance, it sure looks like Mel McGaha to me. (Talk to you tomorrow night.) Rasco